Born in Kharkiv, Ukraine in 1938, Boris Mikhailov has spent decades pointing his camera at the overlooked, the uncomfortable, and the unabashedly human. Growing up in a Soviet system that valued order and obedience, Mikhailov was used to navigating life in a society intent on keeping up appearances. Decades later, he would become famous precisely for undoing those illusions with his boldly experimental photographs.

Mikhailov didn’t start out as an artist. He trained as an engineer and worked in a state-owned factory that was typical of Soviet era Ukraine. Photography first came as a sideline hobby, a way to experiment and explore, after he was given a camera to document the factory by his employers. But when KGB agents discovered he had developed nude portraits of his wife in the onsite development labs, he was abruptly fired. This was the catalyst that steered him into a lifelong career as a full-time photographer. Stripped of his job, he was left with his camera and a strong determination to use it without compromise.

This uncompromising approach is central to what sets Mikhailov’s photography apart for its raw honesty at a time when photography was typically expected to flatter reality. In the late 1960s and 1970s, he began photographing ordinary local life in Kharkiv capturing candid moments of friends, family and strangers on the street, handling these moments with his signature approach of wit, irony and, sometimes, biting honesty. His early works were a quiet rebellion, capturing not just the official story but the absurdities, joys and struggles that people lived every day.

Later, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, he turned his lens toward the devastating poverty and social dislocation that followed. One of his most well-known series, Case History (1997–1998), is a stark body of work that documents the lives of homeless people in post-Soviet Kharkiv. These images are unflinching, sometimes difficult to look at, but they force us to reckon with realities that are often ignored.

His approach doesn’t offer us easy beauty; he offers truth, layered with irony, tragedy and resilience. In doing so, he reminds us what photography can do at its best: not just record, but confront, question and compel us to see differently. He asks hard questions, both of himself and his audience. What does it mean to point a camera at suffering? What responsibilities do artists have when they show us realities we might prefer to ignore? His images rarely give answers, but they never let us off the hook.

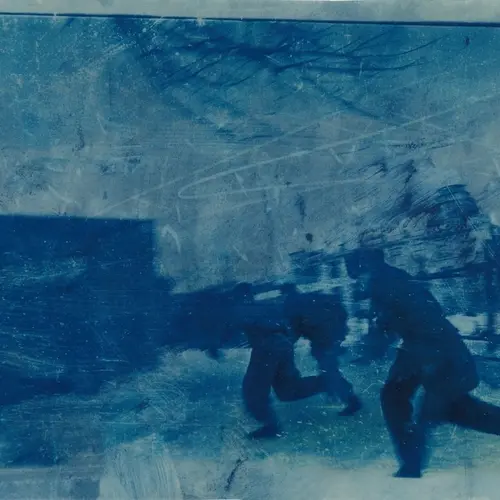

Mikhailov is not a single-style photographer. He has worked in both colour and black-and-white, with smaller snapshots and large-scale prints. He experiments with imperfections, scratches, blurs, overexposures, even deliberate technical “mistakes,” sometimes using them deliberately to highlight the instability and roughness of life itself. His approach has influenced generations of photographers who see in him a model of courage: someone willing to risk censure, discomfort, or rejection to stay true to what he sees.

Despite starting out as an outsider in the Soviet Union, Mikhailov’s work has found its way to some of the most important art institutions in the world. He has exhibited at major institutions such as Tate Modern in London, MoMA in New York, and the Venice Biennale. In 2012, he was awarded the Hasselblad Foundation International Award in Photography, one of the highest honours in the field. Despite his global recognition, Mikhailov remains deeply tied to Kharkiv and Ukraine, both as a subject and as a point of identity. His work is both Ukrainian and universal. Rooted in place, but resonating far beyond it.

Today, as Ukraine continues to face war and upheaval, Mikhailov’s photographs feel even more urgent. His lifelong insistence on showing a stark reality echoes the resilience of a country refusing to be silenced. Just as he once revealed the hidden costs of Soviet collapse, his legacy now reminds us of the power of images to bear witness in times of crisis.