Press play, listen, scroll through the transcript, and take yourself back to Soho then with the images in this photo-based podcast...

Transcript

Clare Lynch: Welcome to episode six, our final episode, of the Soho Then photo-based podcast. I’m Clare Lynch, audio producer and Soho resident. This programme consists of six, themed episodes released monthly over 2018 and 2019. Each episode has a corresponding collection of photographs that you can scroll through as you listen.

In this episode we explore the topic of home and homelessness in Soho’s past. Rina, Violet and Leslie are our guides with contributions from former and present-day residents and workers sharing their memories of Soho from twenty or more years ago.

--

Rina Rottondo: I was born in 62 Old Compton Street on 7 February in 1926. My name is Rina Rottondo,

Violet Trayte: I was born on the 5th February, 1927, and I was born in University College Hospital. My mother at that time lived Goodge Place. And then we moved into my aunt’s, who lived at number 19 Peter Street. And my name was Violet Florence Jones, and now it’s Mrs. Violet Trayte – T-r-a-y-t-e.

Claudio Mussi: Italy was a very poor country soon after the war. There were no job opportunities, so we all emigrated, especially from my neck of the woods. My name is Claudio Mussi, I’m 79. We came over here 21st of October 1961. The employers used to provide you with job and lodging.

Leslie Hardcastle: There was a woman called Mrs Leigh and she lived in number 35 Great Pulteney Street.

My name is Leslie Hardcastle, I’m 92 next birthday. And she used to invite people to dinner and she invited me to dinner and I met all sorts of people in her house. And at the age of 65, she fell in love again.

She just sent me a note saying, “You’ve always loved this flat and I’m going to go and live in Paris. Would you like it?” And by foul means I actually occupied the flat. She paid the rent to the Sutton Estates, who owned the building, and I paid her. And one day they found out that she didn’t live there anymore but by that time I’d actually established a tenancy. So that’s how I started in Soho.

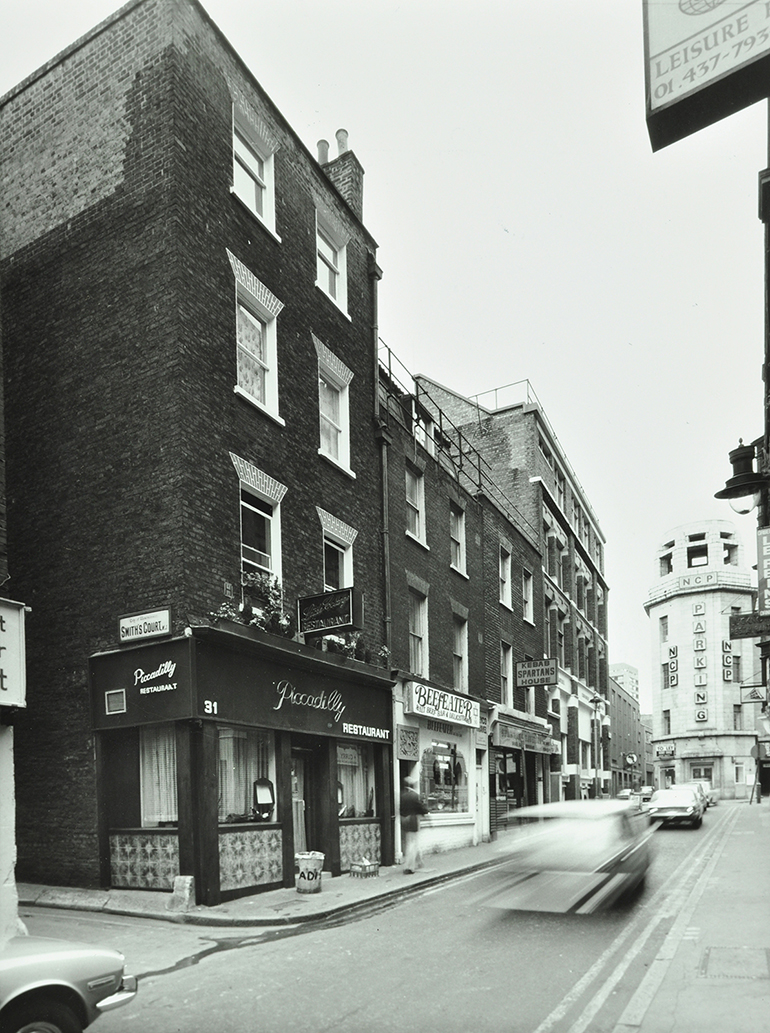

Michael Klein: I moved to Soho in 1972 after I’d met Alan Wakeman. So we’d ended up having a flat and a shop, in Piccadilly Circus, behind the lights.

Lesley Lewis: I was offered a job making costumes and doing choreography for the Carnival Striptease Club which was in Old Compton Street. I had a flat, a studio, and it was a lot of fun. It was a bit dodgy, a bit risky, but it was an eye opener. And that was 1979.

Violet Trayte: My mum moved in here in October 1927. She didn’t like living there, she wanted to come away, so she came into St James’s Residence. And she was in these flats ‘til she died.

Violet Trayte: When we lived here, we rented a place, I think we paid five shillings for one room. You used to go into the toilet at night, everybody in that one house. You had the basement, parlour, first floor, second floor and top floor. Two rooms on each floor. Everybody had to share the toilet. If you wanted water you had to get it on the landings, nowhere else. And the tin bath always used to be in an outer place downstairs. And the rats used to be running around.

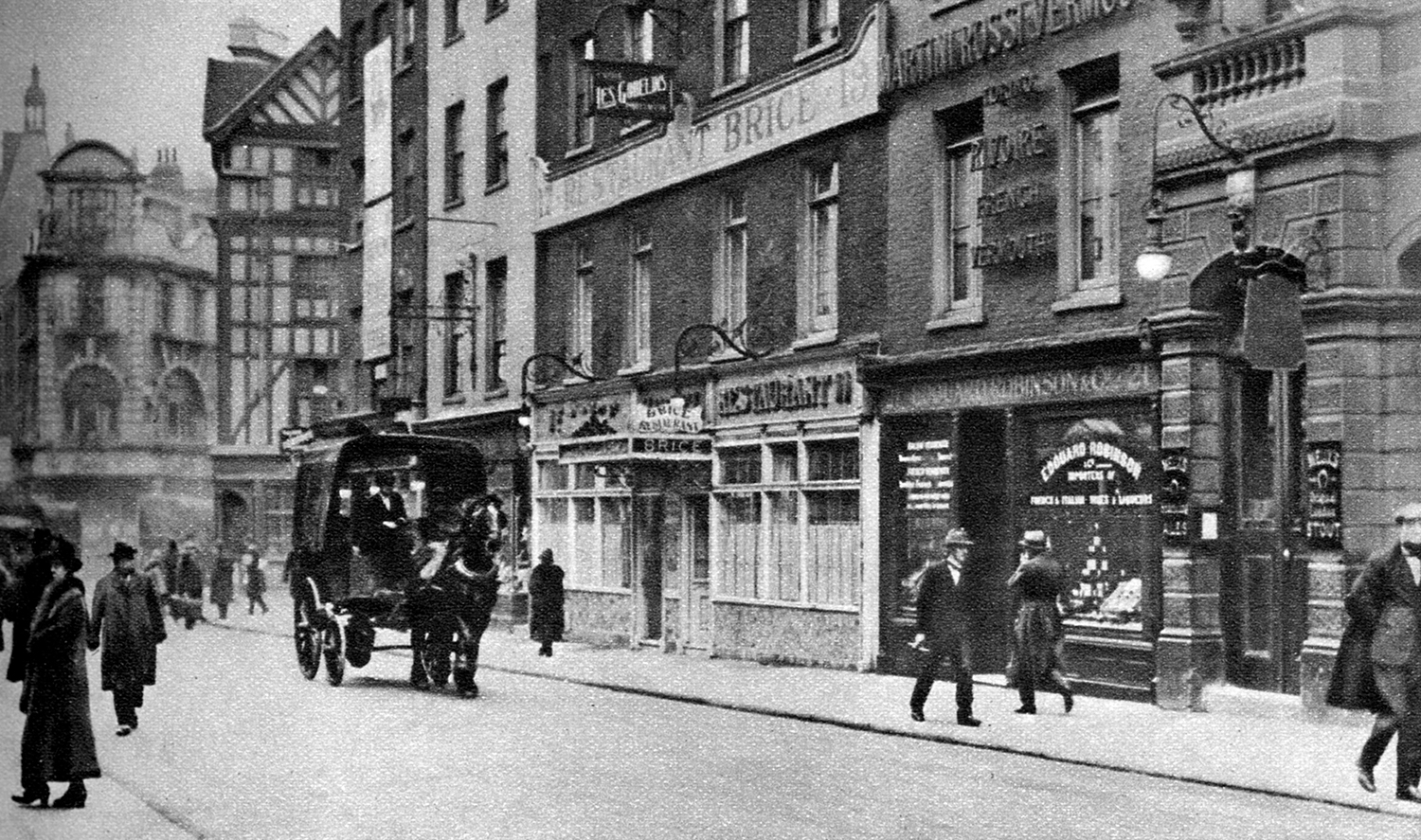

Claudio Mussi: The top floor of the Piccadilly Restaurant, I used to sleep.

One room, with a meter in the corner where you used to put the odd penny, in order to have electricity. There used to be a bath on the second floor, again, we used to have to put pennies in the meter, turn the meter in order to get the gas to have a hot bath. We used to work six and a half days a week, for six pounds a week. The restaurant was a snack bar at the time on Great Windmill Street.

Leslie Hardcastle: When I used to go to the original, number 35, I used to go to the front door and you’d meet a Greek tailor, he used to say, “Buttons! Your colleagues love buttons! They cannot make button holes! Young people cannot make button holes!” And I’d say, “Yes, yes, yes, yes…”

So I’d pass him and then I would meet Bernie Levine and he’d say, “Did I ever tell you the time I saw Jack Spot stabbed, I was buying a cabbage in Old Compton Street and he came in and he fell down and I got blood on my cabbage!” I later found out that was a complete lie because he was actually stabbed in a club.

And then behind him we had Oscar Oswald, a magician, who was an ex-policeman and he used to sell tricks. And he blew up on a Saturday and nearly set the building on fire. But then you’d go up the stairs and there were five pieces of Welsh slate screwed on the side of the building, as an afterthought, for a loo. And that was shared by these three people downstairs, ourselves, the people above us and the people above them.

Violet Trayte: Now when I came with my husband he was living in Silver Place with his mother. But apparently they had to move because there were children over their head and the mother couldn’t stand it.

So the Sir Richard Sutton Estates gave them a place at number 13 Ingestre, so she had the top flat which was two rooms, their own toilet on the landing and the kitchen was out on landing, if you understand my meaning, where they had the cooker. So the son had the back room for himself, and his mother had a put-you-up bed that she used to sleep in. And then when she died, we managed to get the flat.

Leslie Hardcastle: Then you’d go into our room, which was a magnificent room. It was about 15 feet square and about 12 feet high. And one side of the room you used to fold back the shutters and you used to into the next room, where they used to have receptions, when it was a big house belonging to one person.

But now, you’d go in there and you’d open the little folded door, and you’d see our bed and then you’d see our sink and you’d see our bath and a piece of string with a curtain, hiding the bathroom view. And then you’d see our kitchen. So it was like that.

And above us we had the Italian Augusti family who used to have this fantastic row every Sunday and ‘crash, bang’, “I’m gonna leave, I’m gonna leave – you’re dominating me!” The mother used to be very dominant, she was a widow, and she used to say, “Your father wouldn’t allow this!” And actually, there was a cartoon of the father on the wall, because he was a chef at the Savoy.

And I said to this boy one day, “Well, are you going to leave?”

And he said “Yes, I’m going to leave.”

“Well, how old are you?”

“48.”

[laughter]

And then above, there was a pilot, a Comet pilot. You only saw him occasionally. He always seemed to have a different wife every time he went up. And the whole lot was like that.

Violet Trayte: We got married in 1960. A French lady made my wedding dress, and it was a plain dress, that was all, with some Freesia for me to hold. And that was lovely. We had the reception at the Trocadero restaurant, it was beautiful.

Lovely carpet as you went in, big chandelier. We had a lovely hors d’oeuvres, then a main meal. Then we had champagne. Then after that we all walked back to the flat. And we all had a chat and what have you. And then in the evening I had 40 people come into that little flat in Ingestre Place. And they were all sitting on the stairs where I had my wedding cake and the brioche with everything in it for the evening meal.

The block of flats where I was was a block of ordinary flats owned by the Council, with the big gates on the door. And you had the courtyard. But you still didn’t have any bathrooms, but you had your own toilet which was nice. And we used to have a blue plaque on that building, in Ingestre Place, “This building is for the working class”.

Leslie Hardcastle: And there was, right down to the end of the street on Great Pulteney Street, going into Brewer Street, coming up on Bridle Lane, you had six houses and probably a dozen shops. It was a Georgian group of houses and Sir Richard Sutton Settled Estates decided to sell it or lease it to somebody. And all these people got together and formed a tenants’ association.

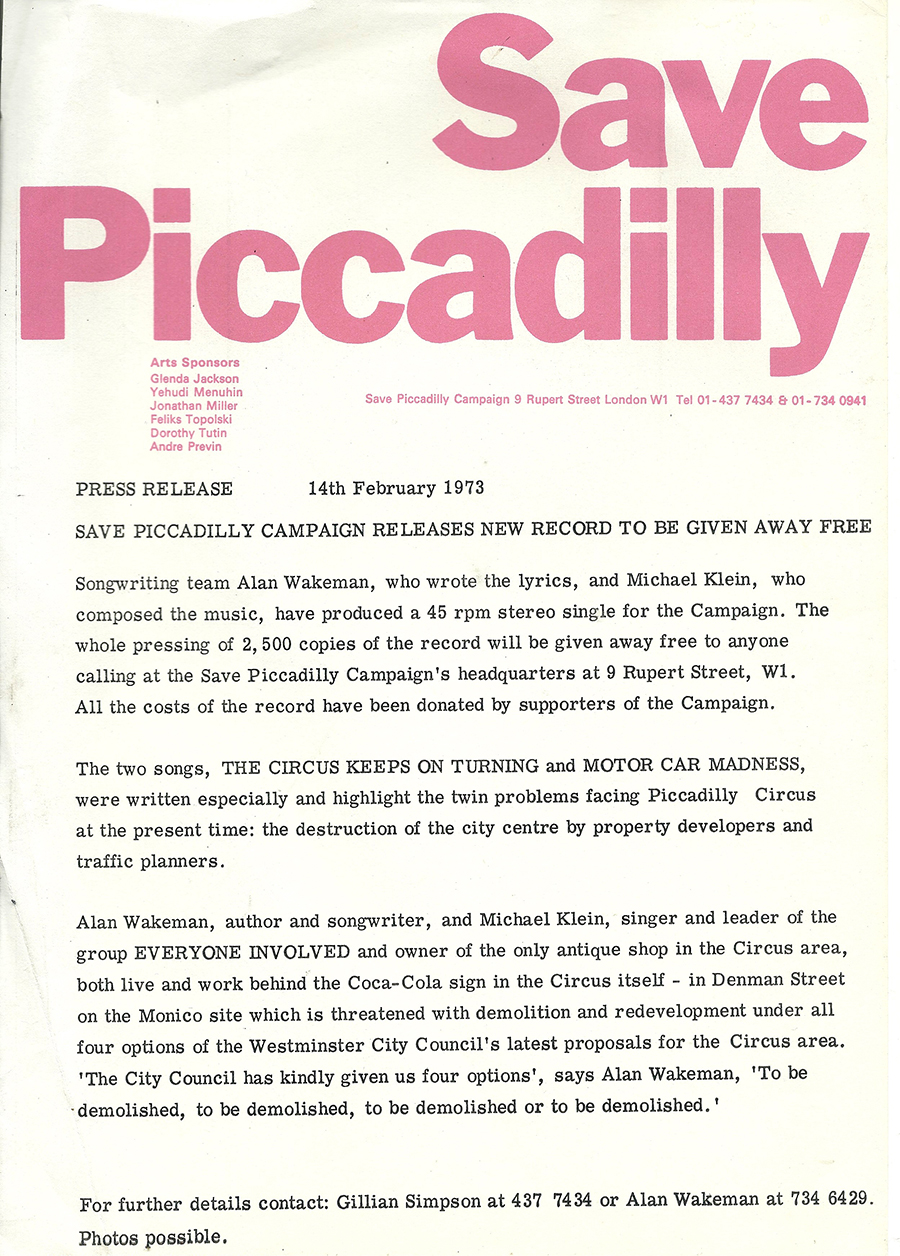

Michael Klein: Alan Wakeman – who lived above me and who was like a brother – he and I started writing songs in 1967 and Alan’s always been the campaigning sort of person. And I was sort of drawn into his world of campaigning.

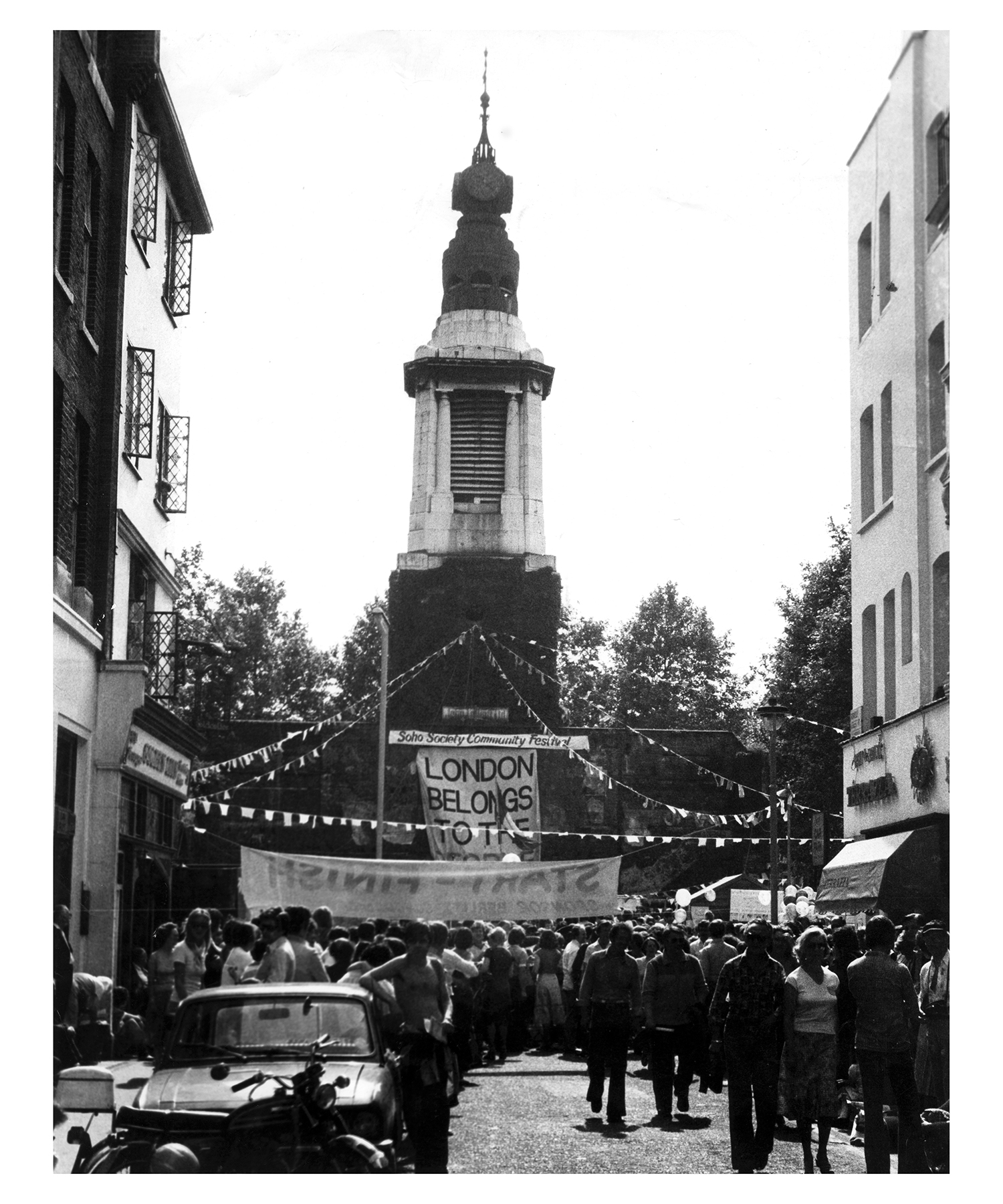

Leslie Hardcastle: The early photographs you see of the Soho Festival, we’d got this big banner saying “London belongs to the people”. There was a big march called ‘London belongs to the people’ and we took part in that as well. And that was our banner, we walked down Regent Street, ‘round Trafalgar Square, because what was happening at that time, there was an office building plan going through the whole of London.

Tim Miller: You know, it was absolutely wonderful to see the slogan ‘London belongs to the people’, in our differing ways, and coming from our differing backgrounds. We all individually believe it, because Soho’s bang in the centre of London and it was the only non-rich bit in the centre of London. You know, it was shabby.

Michael Klein: When we heard the transformation of Piccadilly Circus plan, which was clearly going to affect Soho, which proposed a dual carriageway, highway, going under Piccadilly Circus. We didn’t want that, we thought that Piccadilly Circus was the heart of London.

Leslie Hardcastle: Most of Soho, they thought, was past its use and should be pulled down completely. And something entirely new should happen there. It was called the Jellico Plan, and that plan was actually passed, which covered the whole of Soho or most of Soho with a big platform, with five towers and a heliport on the top and somewhere underneath were the people.

Michael Klein: Surely the property developers could see this. But, of course, they didn’t. Property developers never see anything but the buck at the end of the road. And, of course, with the support of Westminster City Council at the time, they thought they were going to push through this enormous development.

Thankfully common sense prevailed. And I like think that we had a small part in it. We all contributed to saying, “No… We are not prepared to accept this, we live here. There are 5,000 people in Soho. This is a residential part of London, which is what gives it it’s charm and perspective.”

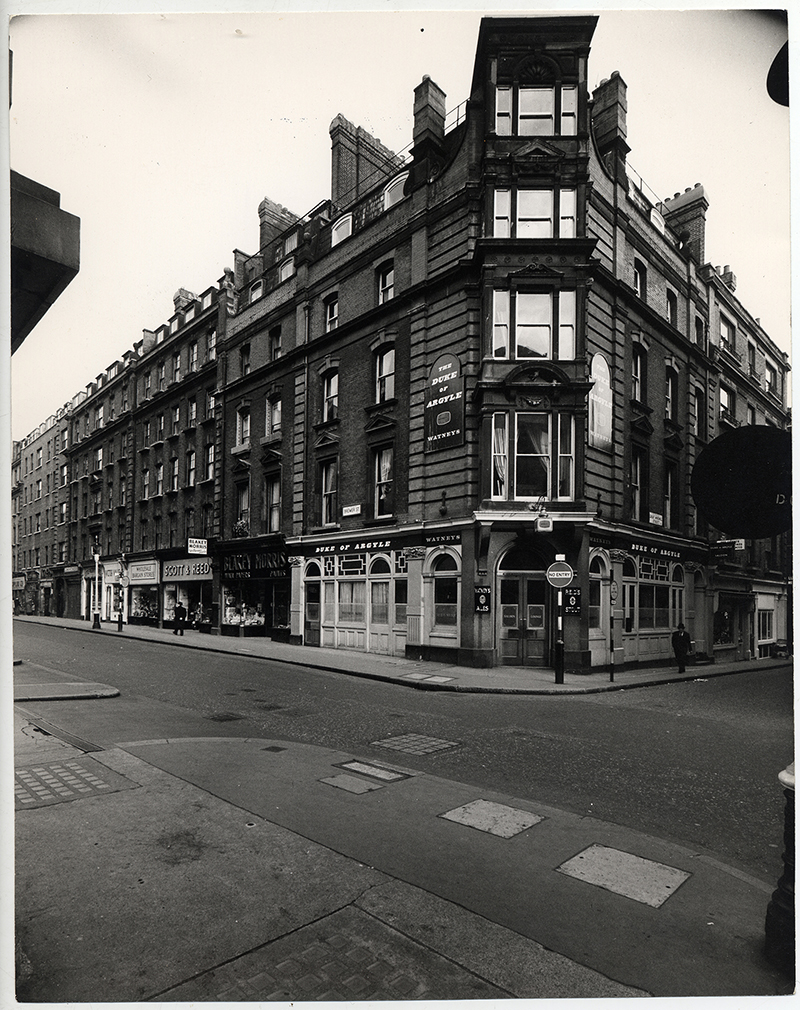

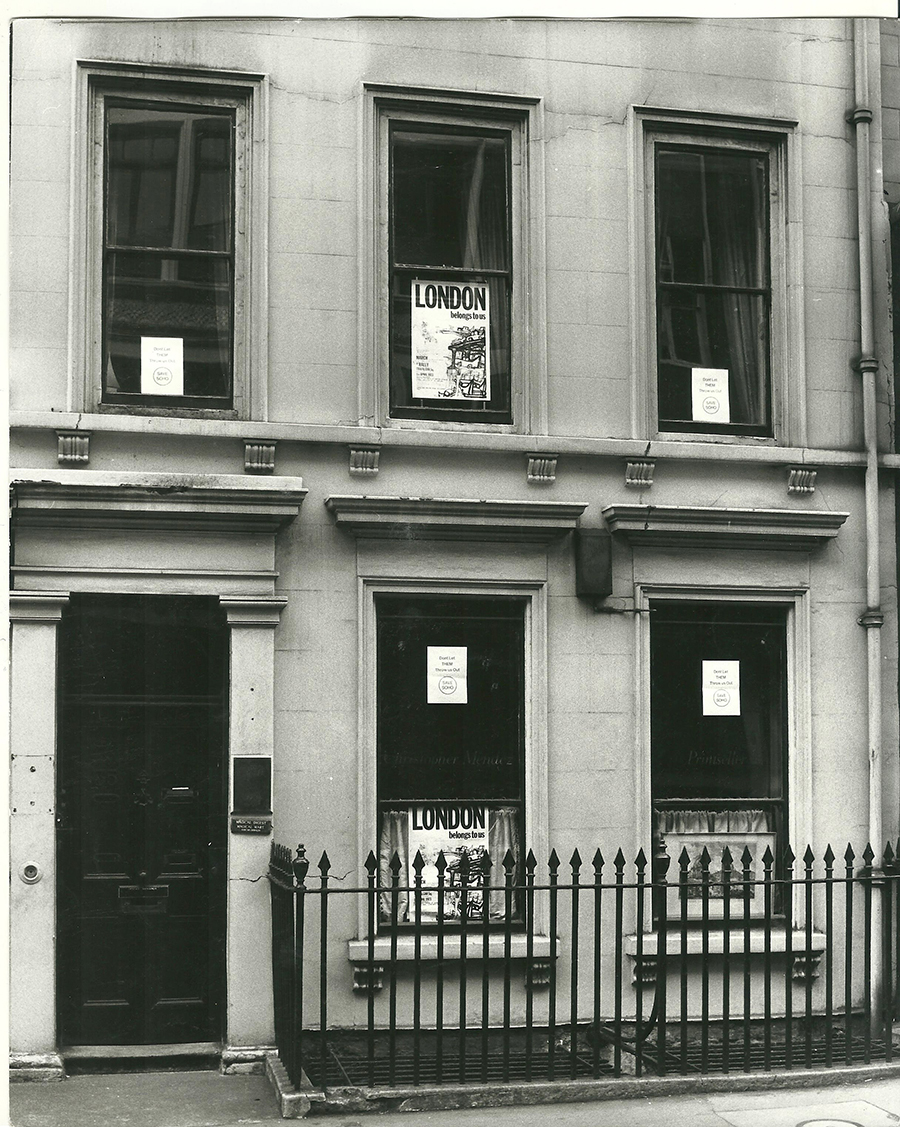

Leslie Hardcastle: That particular building [above] is where we live. And like all the rest all the windows are walled up because they were going to try and get us out. We were living behind that and fighting to save the building.

Michael Klein: And so we did what we could. We wrote about it. We screamed about it. We wrote songs about it, singing our Piccadilly Campaign song, ‘The Circus Keeps on Turning’. We said “no” and we said “no” in the best way that artists could.

Leslie Hardcastle: And just when that was happening, the Act for Listed Buildings came in and we fought to get these buildings listed. And we only got the houses listed, six of them, the rest went. The shops went and the stables behind the big houses also went.

But within those stables and those shops we had something like about 60 different crafts people, because Soho was full of crafts people. You could get anything you wanted made in Soho. And I can quite confidently say, that building’s there because of Wendy, my wife, and myself and the probably 15 to 16 people that really fought for that building.

We held on so long that the property developer, who had taken a contract out from Sir Richard Sutton Settled Estates, went bankrupt. And by this time we had formed the Housing Association, and that was the first building we actually bought out of a grant.

Lucia: I first came on my own to Soho in 1982. My name is Lucia, I’m 53 years old.

Tim Miller: I’ve lived on the edge of Soho some 50 years which is about the length of time that I’ve been involved in Soho. My name is Tim Miller.

Lucia: So the first time I went down there I went down Carnaby Street and that was the place to go if you were a mod or a skinhead, and I was a skinhead at the time. And it wasn’t anything like when you go up there with your friends and you’re in a group, it was quite lonely. And lots of people, lots of tourists around. And I didn’t really know what I was doing or where I was going.

And then I spotted a mod in a parka, and I thought, “Oh, I’ll follow him and see where he’s going.” And he went into the flea market. And at the top of the flea market, there were lots of really cool kids hanging around. And somebody started chatting to me, one of the skin head lads. Everyone was just really friendly, probably a little bit older than me, two/three years older, I was sixteen at the time. And I was just wandering around with a friend, I didn’t really know what I was doing. I’d had a massive row with my mum, I’d run away from home, was determined not to go back. And this was the only place I knew in London. [laughter]

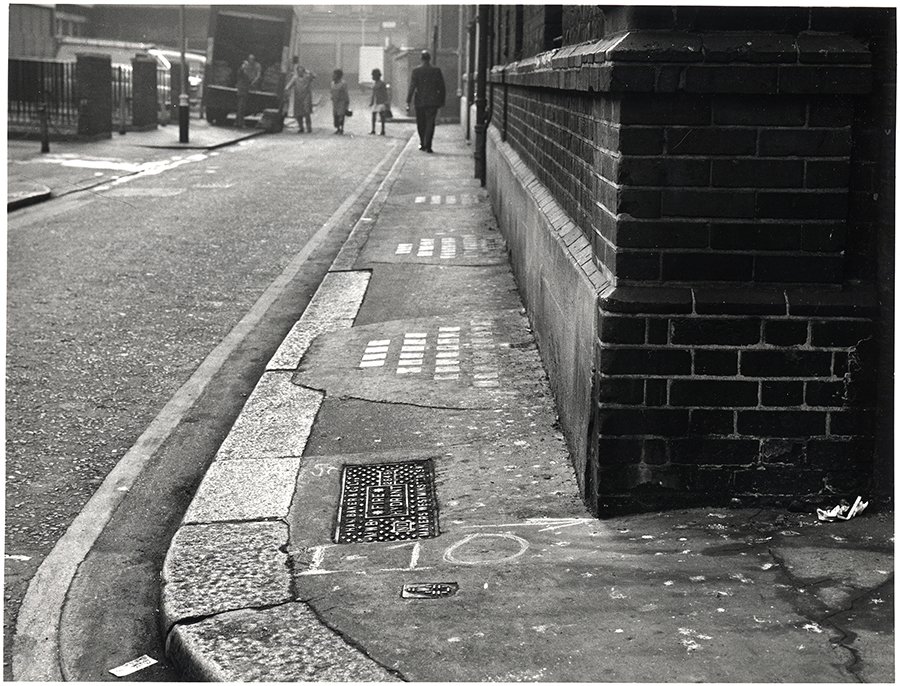

Tim Miller: There were an awful lot of homeless kids on the street. Then people saw what they hadn’t seen before which was a lot of kids sleeping against the hot air ducts outside the Savoy Hotel in winter, for instance.

Lucia: My mate decided she was going home. She got the train back and I was left there on my own. Now, if it hadn’t been for these people that I spoke to in the flea market, I’d probably have been on the streets a lot sooner. But they took me under their wing and they were like, “You got to be careful in the West End because under 18 you’re classed as a ‘juvenile at risk’ so you’ll get arrested. So you can’t be seen loitering and hanging around the streets like tourists do.”

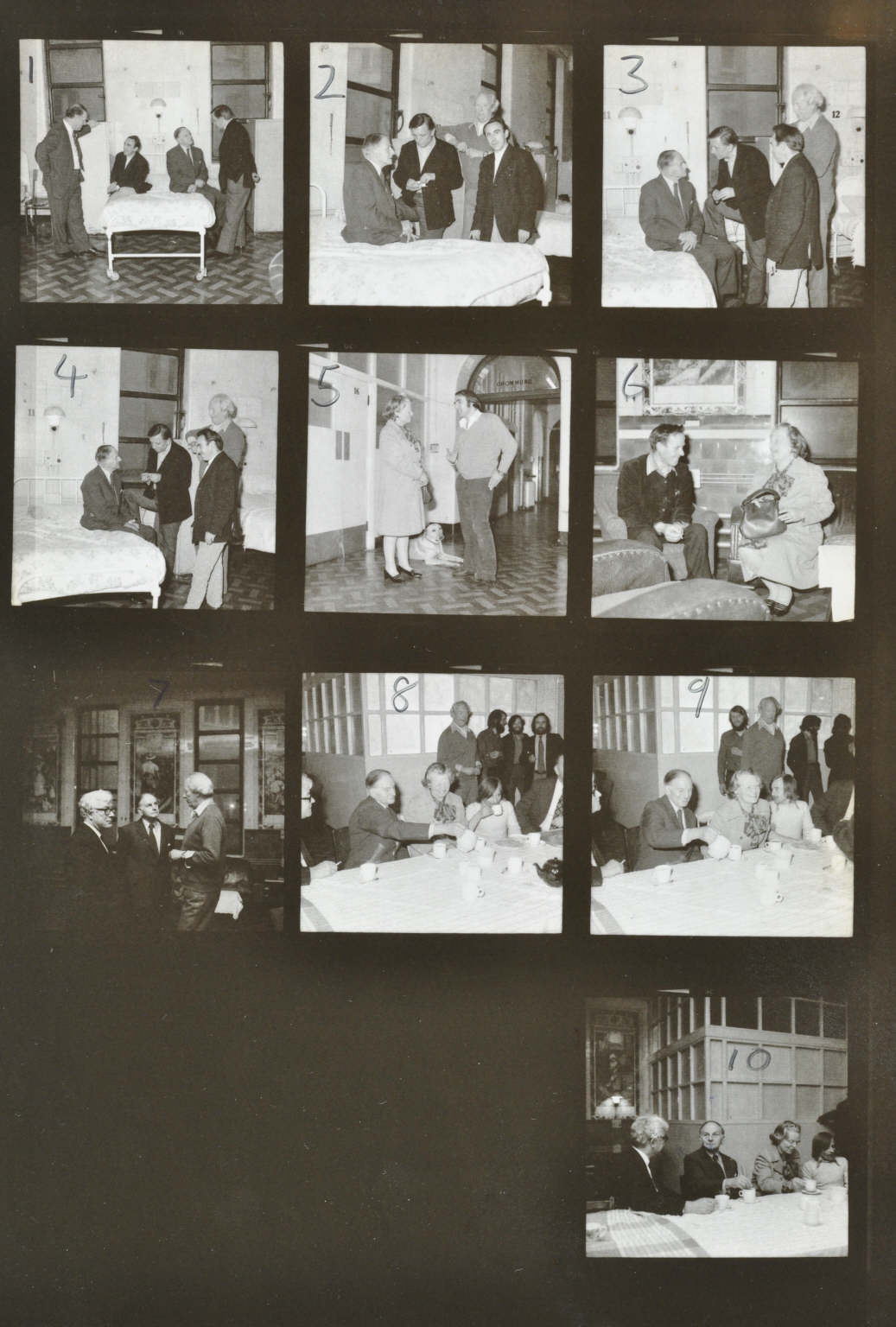

Tim Miller: If they were under 16 there was a legal obligation to contact the police. So everyone claimed to be over 16. There was a group of small charities. Centrepoint was running this night shelter. The Soho Project which was in Charing Cross Road, an office in Charing Cross Road, was working in the street. New Horizon was in Maplin Street in Covent Garden, but worked on the street.

Lucia: Then one of the girls said, “Where are you going?” and I said, “Well, I haven’t got anywhere to go, I’ve run away.” And she said, “Well come with us” and we ended up somewhere in Seven Sisters somewhere in a squat which was like hideous. I really [believed] the old thing of “the streets are paved with gold”. I was squatting and hanging around, sleeping in cardboard boxes at Charing Cross Station, getting moved on by the police, being in doorways and getting moved on. And if that happened we used to hang around in a café by Trafalgar Square. That was always open really, really late.

I was warned quite early by a lot of the lads not to hang around Piccadilly because of the people trying to get teenage prostitutes and rent boys and things. I really [believed] the old [saying], “The streets are paved with gold”. Through one of the girls I came across somewhere called Centrepoint.

The first couple of nights I went there I queued up, I was right at the back of the queue, I didn’t realise that you had to be there two hours early to get at the front of the queue. I couldn’t get in, it was too late. And then you just have to wander the streets.

Tim Miller: It opened at 8, and the team came in well before 7, after their ordinary day’s work and you have to be ready to stay there ‘til midnight.

Lucia: So we used to wander ‘round different cafes and things and that’s where Soho came into its own really because it’s [got] a real, late night buzz about it. Lots of places are open ‘til really stupid o’clock, there’s lots of people around, so there’s safety in numbers as well.

Tim Miller: The difficult thing was ‘doing the gate’, and the gate you had to – through the old gate on Shaftsbury Avenue – people had to be interviewed in a very rudimentary style, to try and see whether they wanted to come in to sell drugs or whether they wanted to come in because they were desperate or they wanted to come in because they were hungry.

Lucia: It was really really dark. It was absolutely teaming down with rain and there were these big gates, quite ornate, but like they were trying to keep everything hidden. Which I suppose along that road they would do, the amount of tourists and things you get there. But the queue of people was really, really long and they were mixtures of all ages and things. And in fact probably, as probably one of the youngest at that point, I didn’t realise Centrepoint was for young people. I thought it was for all homeless people because I think what I didn’t appreciate then was though they might have looked older they actually weren’t that much older than me.

Tim Miller: Every young person that came in was interviewed. They were given a large mug of coffee or Bovril. The main thing was to make them feel safe and make them feel welcome. But that was difficult because quite a lot were on the run from something.

Lucia: So they used to take all your name and details and everything and then they’d go in doors and you’d think, “Oh…” and they’d say to you, “We’ll be back in a little while, we just need to check some information.” And then you’re panicking because you’re thinking, “Well, what are you checking? Are you checking with the police that I’m a teenage runaway? Are you going to find my mum and dad?”

But I didn’t really have anywhere else to go so it was a case of putting up and waiting. Eventually they’d come back, so I was intimidated and scared in the beginning, without a doubt. I really thought they were going to ring my mum, and I was going to get dragged back home, you know. I just couldn’t go back there. When they came back and they say, “Oh, yeah, you can come in.” And they used to give you bag with a toothbrush and a little toothpaste and little bits and pieces.

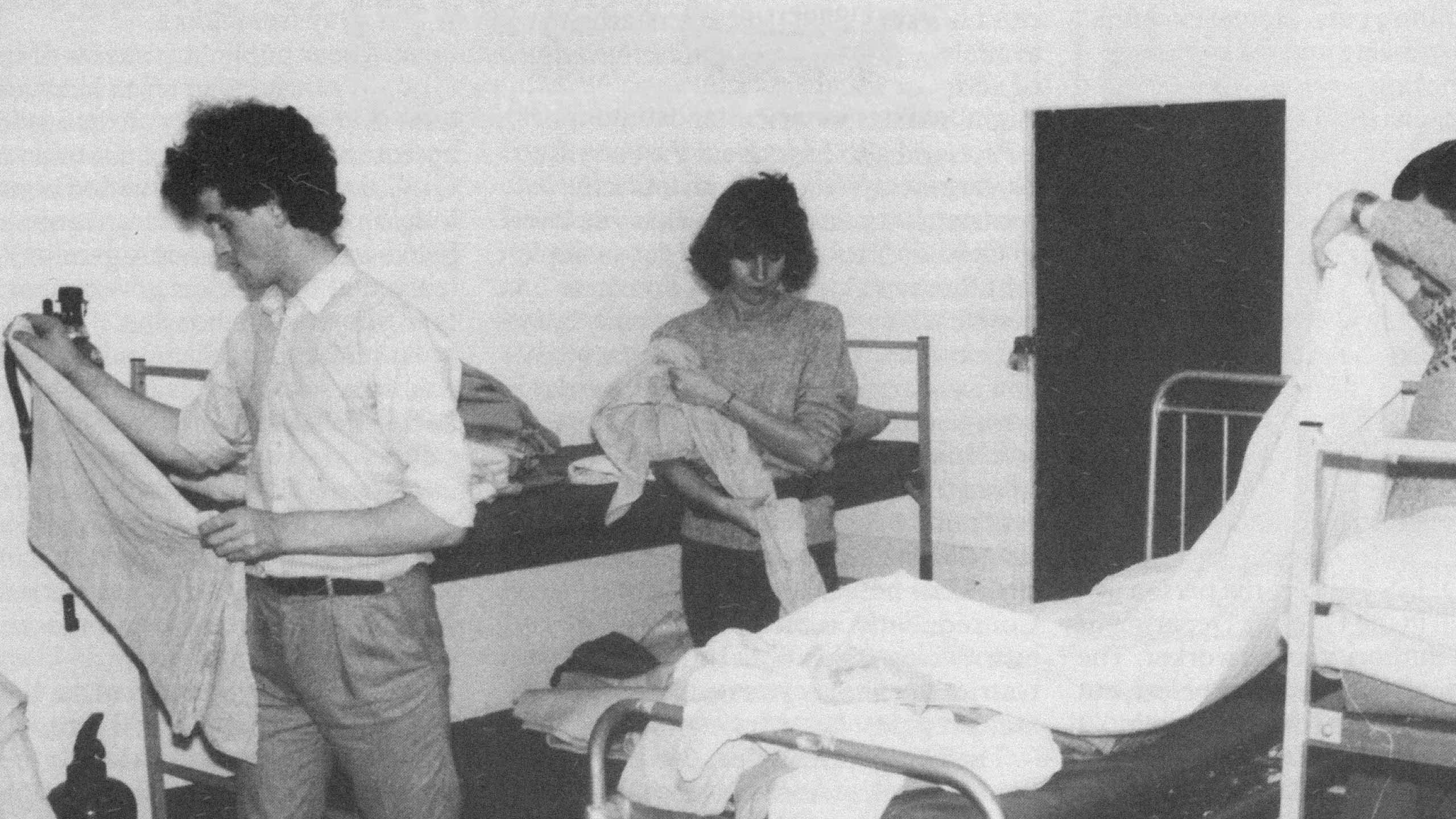

It was a big basement room. It was like a huge basement. It wasn’t pretty. It was just a bog-standard basic room with rows and rows of little camping beds with little pillows and blankets on them. There was at least a blanket on every one of them. And there were showers, as well.

And I just remember sitting back and thinking, “What on earth have I done? What have I let myself in for by coming in here?”

But actually, the staff in there were brilliant.

Tim Miller: And after midnight just a few stayed to give the people there breakfast and to see them safely off at 8 o’clock in the morning.

Lucia: You come out in the morning and you’ve been in this really dark basement. And you come out and it’s light outside and it’s grey and it’s dull and it’s cold and it’s wet and you think, “Ok, where are we going to start wandering now?”

And they used to give you luncheon vouchers, they used to give you luncheon vouchers and you could go and get some food at a caf or something. I can’t remember how much they were for – not much but enough that you could get a sandwich. Different cafes used to have signs in the window saying ‘Luncheon Vouchers’.

Tim Miller: I think Centrepoint did a lot of pioneering work and that all came from Ken Leech and the people he knew.

Lucia: I know that they were trying to persuade me to go home, that it’s not as bad as you think it is. And actually they were quite right. So, yeah, Soho was a really cool place to be.

Leslie Hardcastle: Save Soho!

--

You’ve been listening to the voices of Rina Rottonda, Violet Trayte, Claudio Mussi, Leslie Hardcastle, Michael Klein, Lesley Lewis, Lucia and Tim Miller, with added field recordings made by the Radio Enrichment Group at Soho Parish School. Soho Then is a photo-based podcast produced by Clare Lynch and commissioned by The Photographers’ Gallery, a Soho-based public gallery dedicated to photography. Soho Then is s financially supported by The National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund and #MyWestminster Fund. With thanks to National Lottery Players.