There is a quiet murmur in The Photographers’ Gallery, as visitors glance from image to image. On the fourth floor, is the display of Lindokuhle Sobekwa’s photobook I carry Her photo with Me, in multiple formats. The sound, music titled: Meditations for Ziyanda: Siyokukhumbula (2021) composed and performed by Nduduzo Mahkathini plays, encircling the gallery space. Images flicker as they are projected on a wall. A selection of framed photographs from the photobook faces the projection.

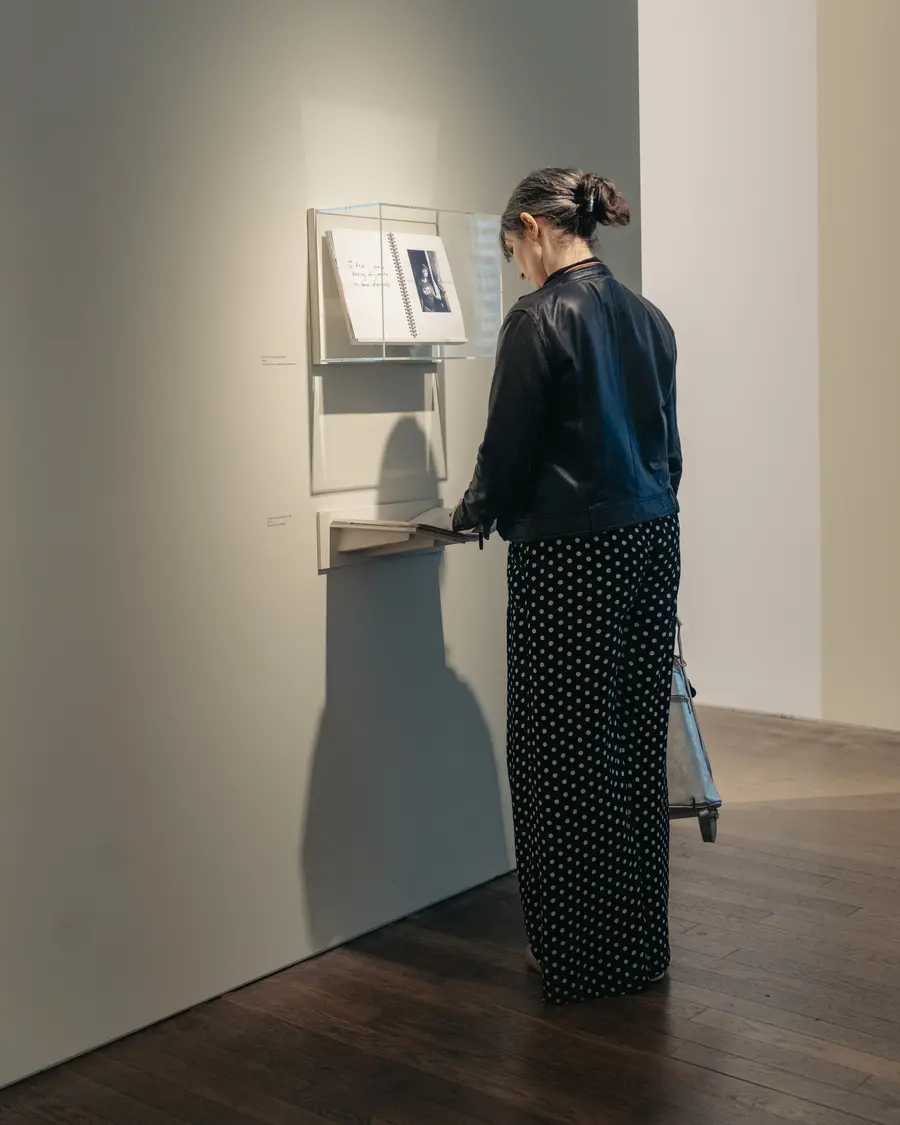

There are two copies of the book itself. One, the original maquette, shows a portrait of a young woman gazing directly into the lens with the words “I felt I was seeing Ziyanda in her friends” written on the opposite page, encased in glass. Her arm rests on a window sill, and a shadow envelops part of her profile. The other copy of the book sits directly below it with lightly worn pages on a stand. People move through the space, they examine the images on the wall, they read the text, they sit and watch the projections - but with the book itself, they are hesitant.

There is a hesitancy when invited into another person’s grief, especially when it is situated in its wider historical and socio-political context of Apartheid and colonialism in South Africa. Sobekwa plays with light and texture beautifully and the materiality of touching a photobook this profound and reflective can be overwhelming. We are not often allowed to touch an image in a gallery space. Upon opening the book, I found myself moved immediately to tears, reminded of those sacred ancestral family albums taken off the shelves during special occasions. I moved slowly from the first to last page. Grief is something only those who have experienced it can fully recognise in another.

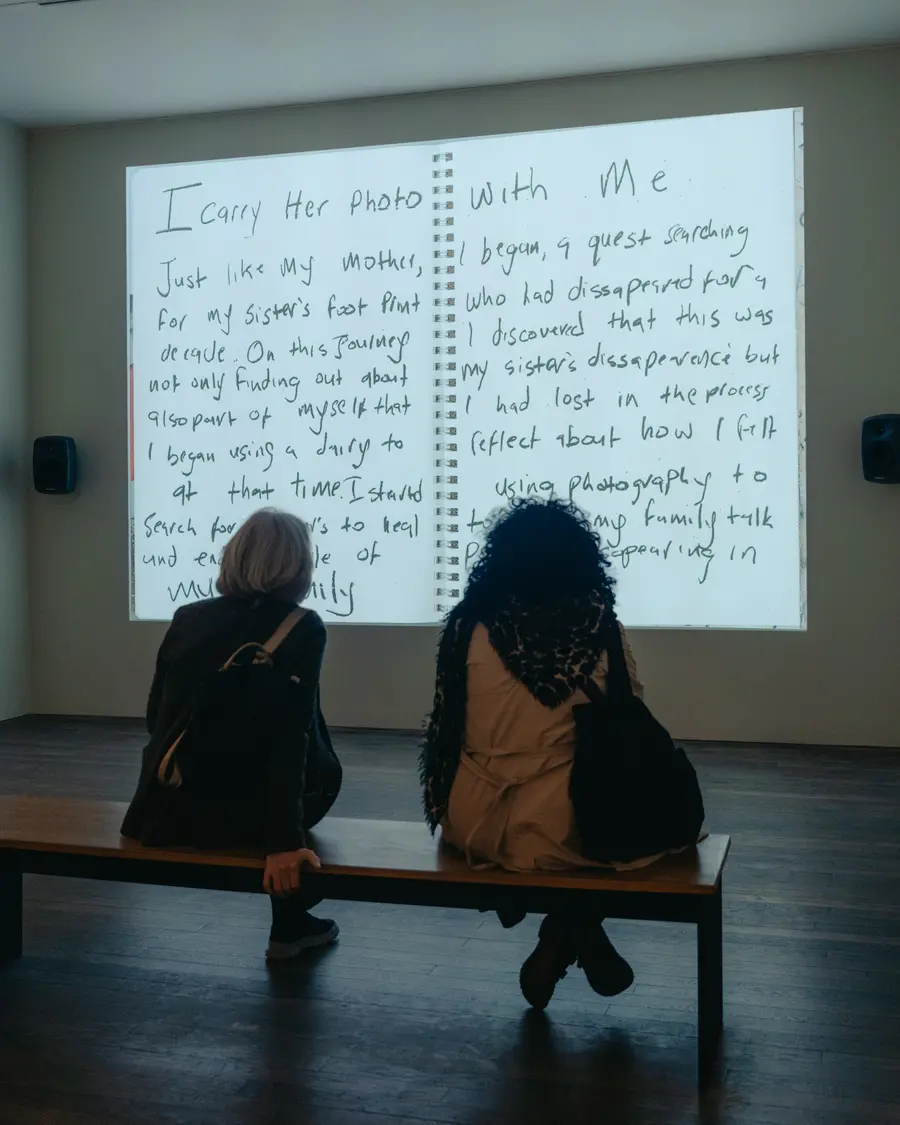

The intimacy of witnessing an artist process a loss - the magnitude of the loss of a sister. Ziyanda’s disappearance shaped his life. Her return further shaped it. Then her death. Sobekwa’s annotations provide alternative accounts and offer diaristic-style thoughts to the already moving frames he captures. Revealing criticisms, reflections and thoughts to an audience is a level of vulnerability that invites us to participate in the processual nature of photography, beyond merely technical steps, adding layers of meaning to a work - inviting engagement in multitudes. The most vivid of the annotations is a photograph that he has scrawled on with red crayon. This mass of red - almost violent in its vividity - has a child-like, but also forensic quality to it. Tacked to the wall amongst the glossier framed photographs, larger in scale, it disrupts. One immediately knows it is a core moment in the artist's life.

The medium is time travel, and the annotations that Lindokuhle Sobekwa scores across the pages communicates the atemporality of grief whilst attempting to piece together parts of his sister Ziyanda’s life.

So often when we are from contexts where imperialism, violence and systematic oppression have shaped our political landscapes, material conditions and familial life, artists find ways of processing and communicating these violences by making the trauma an object. Sobekwa refuses overt imagery - in fact, his textured frames, and

portraits, respect the agency of his subjects. Ziyanda did not like to be photographed in life, so the one small frame of her face, cut from a family portrait, is nestled between many other images near the end of the book. Ziyanda’s face is not reconstructed or reimagined through each friend, Sobekwa extends his respect for his sister, to those of her friends who also wish not to be photographed.

There is honour and dignity in this project.

What does it mean to construct a fragmented archive of a person who refused to be documented? Images themselves are fragmented across the spiral bound book. The bright yellow and red laundry is the opening photograph, and inscribed on the first page is an offering “for my sister Ziyanda.”

Each image whispers to the other, or to an iterative version of itself in another format. They are part of a bigger story that continues to unfold. No singular photograph is more important; they exist as a constellation, non-linear and conversational. There’s a striking image of the artist's grandmother, in black and white, tending to the land, as a tree and its bare, expansive branches stand tall behind her, almost protectively. There’s another, of telephone wires, and a golden landscape at dusk, taken in movement, likely from a car. A pink ruffle dress hangs against a green concrete wall. Sobekwa’s mother is a beautiful subject, as she sits on the edge of a bathtub, or reads her bible at night. Perhaps it is with this grace that we end.

I know that feeling that he writes of, about finding out about himself through this, mediating the most challenging of experiences through the camera. Thank you, Lindokuhle, for inviting us into your grief, you showed me a way of honouring the person in that grief.

Through these small frames from Lindokuhle Sobekwa’s life, we are invited to acknowledge the severity of the disappearances of young women in South Africa. Framing the socio-political context through this personal story implicates us in a visceral way that we cannot escape. It makes sense that in a small corner of the gallery space where people are invited to name their favourite for the prize, Sobekwa’s name is pinned over and over and over.

Find out more about Florenza Deniz İncirli

Florenza Deniz İncirli is a London and Cyprus based artist and researcher, working primarily with moving-image and textual based works engaging with memory, non-linear temporality and ritual performances. Informed by an MA Visual Anthropology and the Radical Film School, their work moves between ethnographic film, documentary and experimental methodologies, alongside public programming.

Florenza has shown work at Kontekst Fest (Set Woolwich), jetz.space, Alexandra Palace, programmed by Haringey Global Cinema Club, Good Wickedry (Tape Collective), BFI, F(r)ictions Tbilisi, Cyprus High Commission UK, Swansea University Egypt Centre, The Art Columnist, Cyens Thinker Maker Space, WIP Festival and Sessions Cyprus. In 2024, they co-founded the reading and research group Critical Coffee Reading, which focuses on the anthropology of Cyprus and other coffee-reading geographies. They have also recently begun refurbishing and public programming at a community centre in Stoke Newington.

Their practice is collaborative, exploratory and multilingual, grounded in community.