… a photo is a literary narrative, ya know what I mean…— Garry Winogrand

… as I watched the play of shadow and light on the fine bone structure of Joyce’s face, I thought of the portrait I could do of him that very moment.

Gisèle Freund

Brian Dillon describes the non-method of essay writing — because it’s not strictly a form that has method — eloquently in his recent book Essayism (2017), which takes something from Anne Carson, E.M. Cioran, William H. Gass and a whole host of other stylish essayists, fusing scholarly research with autobiography. This philosophy — because essay writing is a way of living, too — is also present in Dillon’s essay Photographs, and in the work of many other literary essays on photography, including Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida (1980) to name merely the obvious. Perhaps some of the most pleasurable essays on photography are to be found as fragments in Carol Mavor’s Black and Blue (2012). In chapter 4, Summer Was Inside the Marble, in a section titled I REMEMBER, Mavor writes on a c.1851 photograph by William Henry Fox Talbot and Guillaume Apollinaire’s 1918 poem Il pleut (It’s raining):

I am looking for summer inside a black marble.

I see raindrops like black marbles, like Talbot’s photomicrographs of plant stems.

I see; I hear the calligraphic rain of Guillaume Apollinaire’s Il pleut:

It’s raining women’s voices as if they died even in memory. And it’s raining you as well as marvellous encounters of my life O little drops [o gouttelettes].

I taste the black light, like Barthes’s drops of black milk, like Apollinaire’s drops of black rain.

Writer Marina Warner notes that Carol Mavor has ‘developed a unique way of responding to images and to their uses by artists and writers: with appetite and fastidious delicacy, she brings the full sensorium synaesthetically into play.’ Indeed, Black and Blue is a complex and beautifully composed book, which considers writing on various photographs as a task both for scholarship and for the urgency of personal experience. The essay becomes the vessel in which, as William H. Gass writes in Finding a Form (1996), experience collides with insight to produce language which is ‘the very instrument and organ of the mind.’

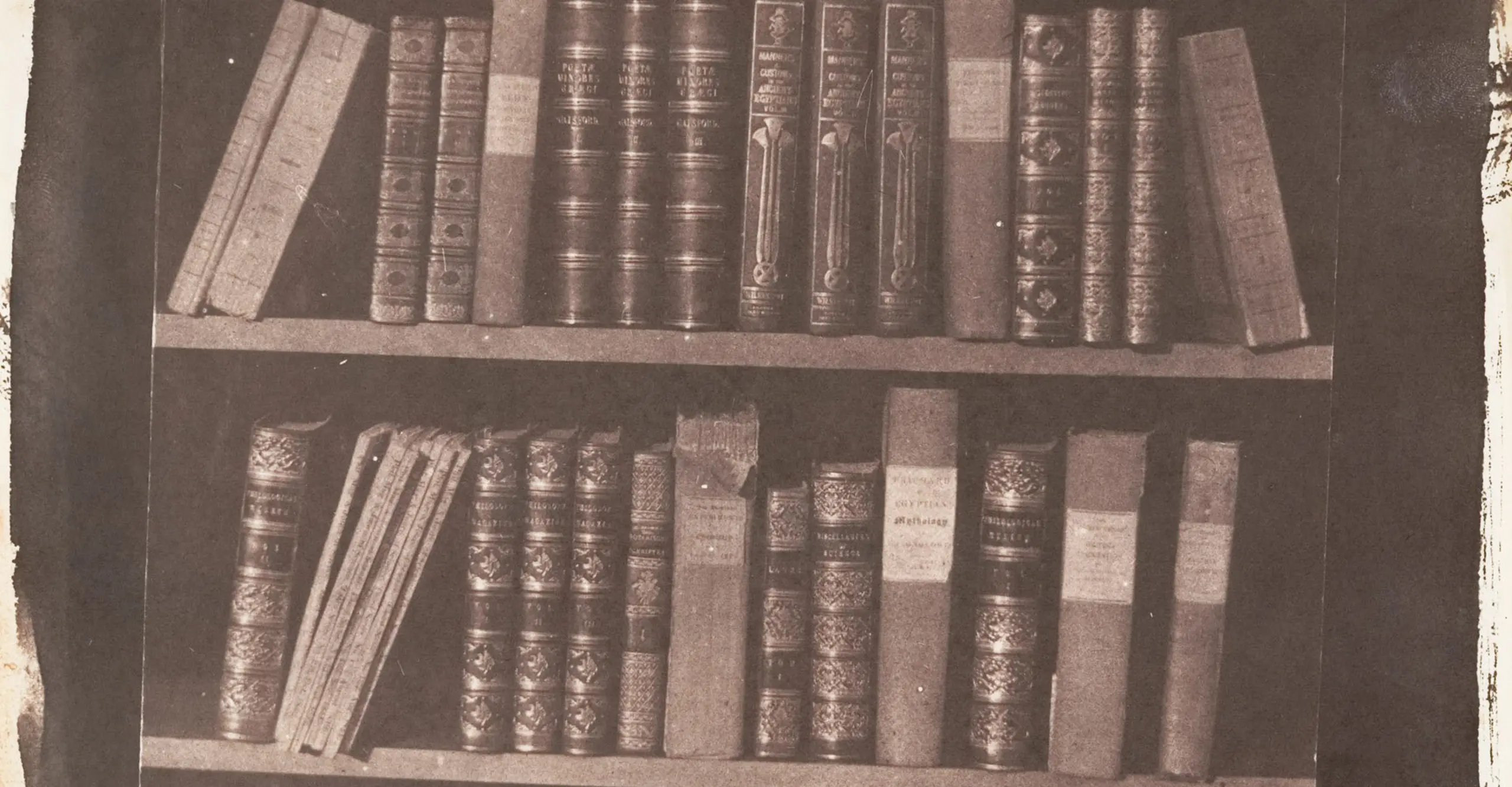

The relationship between the ways in which the photographic might describe literature, and the literary might describe the photograph is a regular occurrence in the history of photography, as we shall see. Carol Mavor describes Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time (1871-1922) as “photographic”; Virginia Woolf writes of Julia Margaret Cameron that her photographs ‘reflect her literary friendships and tastes’; William Henry Fox Talbot associates photography with literature — because books sit still, such is their wont to be photographed — in the above image from 1845, which I borrow from the first page of Jane M. Rabb’s Literature & Photography (1995), where it sits uncaptioned in the form of a visual epigraph — which is to say, a conjoining of the literary and the photographic.

Various historic conceptions of the photographic image have seen it described as the act of “writing with light”. One interpretation of the etymology of the word photography in Greek translates into “light writing”. In considering photography (Greek: fotografía) is the production of images made with light (Greek: phōtós) and finds a relation to the word writing (Greek: grafí), it is no wonder that various photographers have had literature in mind when making images. In his essay Photography or Light Writing (1999), Jean Baudrillard asserts: ‘… no matter which photographic technique is used, there is always one thing, and one thing only, that remains: the light. Photo-graphy: The writing of light.’ Walker Evans wrote that he turned to photography — following his infatuation with the writing of authors such as Flaubert and Baudelaire — as it was, in his mind, the ‘most literary of the graphic arts.’

Conversely, various writers have had photography close at hand when putting pen to paper. The American writer William Carlos Williams was deeply interested in photography due in part to his friendship with Alfred Stieglitz who, incidentally, Walker Evans thought was ‘too arty’ a photographer. Henry Fox Talbot suggested the word “skiagraphy” for his own invention, which conjoins “skiá” (shadow) to “grafí” (writing). Thus, photography is a compound, both linguistically and culturally. To an uncertain extent — lest we over-egg the pudding — photography is writing, be it in light or shadow.

Photography changes nothing. Violence continues, poverty continues. Children are still being killed in stupid wars.

Letizia Battaglia

One might identify at least two modes of writing the photographic image. Although distinguishing between the following may be unproductive, here I want to think about photography’s specific relationship to the essay, as opposed to fiction. This is not to suggest some kind of specious separation between essays on photography as things that deal in reality, and fiction writing on the photographic image as a thing bound to the make-believe, but rather to concentrate on the convoluted relation between two things that cannot be fully separated. The photographic image is both a document and a fiction all at once. Likewise, the essay seems to have a hard time staying in the realm of reality, whatever that might be.

Returning to Adorno’s The Essay as Form, he suggests that where meaning is produced in the essay it does so through the ‘spontaneity of subjective fantasy’. As is the case with the photograph, we might also conceive of the essay as the writer’s meandering consanguinity with the real world. But not only the real world, as the essay strays into reverie, speculation, ignis fatuus — things not altogether real. The essay is a mode of writing that might be produced in order to understand the meaning of photography, but also a form — as it takes various shapes — that writes on the photograph, to the photograph or with the photograph as a means to get closer to it. Essays might describe the bone structure of things, but they also — I think in their most appealing shape — engage the play of light and shadow in considering a particular subject or phenomena. The stuff around the edges; the tertiary; the unexpected. Like Lucretius’ flying simulacra, the essay engages ‘atom-thin and lightning fast’ images as they slip off the surface of the objects they once constituted and float around looking to be interpreted. At least that’s the way I see it, if you’ll permit me the spontaneity of subjective fantasy.

One history of photography is a history of writing. Rabb’s Literature & Photography demonstrates this well as she traces the interactions of the photographic and the literary from the middle of the nineteenth century to 1990. Containing a number of essays on photography or photographers by notable writers, alongside fiction writing in which photography plays a crucial part in character or plot development, Literature & Photography confirms, in no less than 100 examples, the various reciprocations between two celebrated cultural forms. In a 2009 book, Photography and Literature — which swaps around the word literature with the word photography to form its title, and prefers the less ornate “and” to the ampersand — the French writer François Brunet suggests: ‘the invention of photography must be envisioned squarely in its written condition.’ In a review of Brunet’s book, the American writer Alan Trachtenburg notes: ‘photography frees itself from painting, aligns itself with writing, and then, in the current condition of “interaction,” arrives at a hybrid state between the visual and the written, now charged with the mission “to image literature”’.

In her The Miracle of Analogy (2015) — the first of a two-volume history of photography by the American writer Kaja Silverman — the well-trodden notion that sees the photograph named as an indexical or representational thing is replaced with a description of the photographic image as the linguistic and literary form of analogy. Instead of the photograph offering meaning through memoriam or remembrance — as an image that traces linear time from past to present to future — Silverman’s photography is trapped between similarity with the real world and ontological difference to it. Profoundly, the photograph is an ‘authorless and untranscendable thing’ that structures Being. She quotes Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass (1902) in order to expand her definition of this “in-between” state of photography, and thus makes a second allusion to things literary. Silverman’s Whitman-like photography is ‘spherical’, ‘grown’, ‘ungrown’, ‘gaseous’, ‘watery’; tied between being all lives and all deaths; all civilisations and all languages — both human and computational — across all time. Moreover, citing the philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Silverman calls her photography as analogy a “chiasmus” — like the upside-down image of the camera obscura, this photography places the very nature of Being crosswise. In this sense, photographs are back-to-front sentences, syntactically disordered; forever inversed and transposed.

Let’s surmise a strange parallel. In order to make a photograph, one might undertake similar mental and physical processes as when one writes (simply, identify a position and compose it). Or alternatively, we might talk about photographs and come to an understanding of their meaning in the same way as we do with writing: we can consider the semiotics of the photograph, or the image-as-text, as several have done before, including Roland Barthes, Allan Sekula and Laura Mulvey. In a 2009 essay, Ari J. Blatt uses the word “phototextuality” to refer to the hybridisation of photography and literature. We can also conceive of the digital photograph as a written code, a machine language, a series of 1s and 0s. Binary code forms the image as data and the digital photograph is constituted by what programmers refer to as low-level or high-level language. Indeed, the hottest topic in contemporary photography theory might just be discussions had between those that advocate a “semiotic reading” of the photograph, and those that are bit-by-bit building a philosophy of the photograph as an “image of computation”. What is linguistic about the photograph is constructed, and what is visual about the photograph is projected, or conjured in relation to whatever we might call reality (which some neuropsychologists posit to be a construction too). Photography and writing can’t be precisely the same thing — be the relation literary or computational — but there are evident parallels nonetheless.

What might this mean in terms of style where essays on photography are concerned, and what of it might be absorbed, or rejected? What I want to ask — but may not be able to properly answer here — is what is the politics of essay writing on photography? In my view, when we think about writing on photography, we are in essence thinking about the relationship between photography (object of enquiry), style (the form and manner of execution) and politics (the social meaning of the writing produced). As Ariella Azoulay demonstrates in Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography (2009), the photograph is political; and if the photograph is also literary, we find photography, literature and politics in close proximity if not complete amalgamation.

The reason I might both accept and resist the “principal elements of style”, as Strunk & White phrase it, aside having never formally learned any aspect of it beyond GCSE English (and therefore I count myself a keen novice), is because style also simultaneously reveals a politics; a way of organising the social world of writing on photography. Or put differently, style is socially constructed. Psychological research into the ways in which written expression takes place sees the process of writing broken down into three areas of inquiry: cognitive, social-constructivist and neuro-developmental. Sparing the detail here, and by offering a sweep of Kim Fitzer’s essay Review of Theoretical and Applied Issues in Written Language Expression (2003), her research specifies that the process of writing is dynamic. Writers move back-and-forth (like chiasmi, forms that criss-cross) between visualising, note-taking, planning, writing and editing in no particular order.

The social-constructivist view relates the principal elements of written expression as they are found in the university and in published works — vocabulary, knowledge of grammar etc. — to social privilege. This is where the question of style in writing gets interesting. The more privileged you are, i.e. the more access you have had to education, the more you’ll be able to demonstrate your ability to execute the canonical toolkit associated with “good writing”, whatever that is (I think good writing is sometimes Susan Sontag, but it is also Kendrick Lamar). One shouldn’t fixate on the vague and subjective definition of “good writing”, more on the possibilities and politics of the essay as a genre.

Unfortunately, this toolkit — a socially constructed academic vocabulary (because I don’t what to call it literary) — has been majoritively defined by men socialised white. If one looks at the literature on “writing and photography” most cited — take for example Mark Durden’s Fifty Key Writers on Photography (37 white men, 12 white women, 1 woman of colour), or Alan Trachtenburg’s Classic Essays on Photography (26 white men, 2 white women, 1 anonymous author, 0 people of colour), or most university reading lists produced in photography departments — one should justifiably ask where are all the women’s voices, the queer voices, the black and brown voices, the gender-fluid voices? As Jean-Jacques Lecercle writes in A Marxist Philosophy of Language (2006), ‘language is also a history, a culture, a conception of the world — not merely a dictionary and a grammar.’ What world has writing on photography conceived of to date, and what world do we want it to live in going forward?

There are some more positive exceptions to the rule of male-dominant bibliographies, including Karen Beckman and Liliane Weissberg’s On Writing with Photography (2013), which situates itself in relationship to, as the authors write, ‘a much broader view of what writing might mean, and in doing so, it makes room for different media, genres, registers and practices that have hitherto been somewhat overlooked.’ Various writers contribute chapters to this volume, including an essay by Xiaojue Wang on the Chinese writer Zhang Ailing that considers the spectral qualities of history and photography in the work of one of China’s celebrated modern writers. Similarly, Liz Heron and Val Williams’ Illuminations: Women Writing on Photography from the 1850s to the Present (1996) does important work demonstrating that writing on photography by women has always been a significant part of the history of the medium, despite numerous examples of obliviousness — ignorance, disregard — on the part of some men. In their introduction the authors ask the questions: ‘Why women? Why leave men out of this ample and capacious selection? It must seem perverse when men have such an active and prominent presence in the world of photography. One good reason is that very self-perpetuating dominance.’

A discussion of photography and the essay must take these questions into account. Language is, after all, not used innocently (the artist Alfredo Jaar says the same of images). To paraphrase Lecercle and quote Jaar directly: words, like photographs, represent an ‘ideological conception of the world’. Following a similar political logic, Lucy Lippard and Carol Naggar have written on the idea of de-colonising photography, and 2002 saw the publication of Deborah Willis’ Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photographers 1840 to the Present. Such important scholarly work, and also such excellent writing, asks for a consideration of the way the histories of marginalised people are thought, taught and read. The work doesn’t stop at the tokenistic statistical novelty of diversifying reading lists or collections of essays on photography, but in what I want to call the “de-centring of literary whiteness”. In their Reading, Writing and the Rhetoric of Whiteness (2012), Wendy Ryden and Ian Marshall note that various scholars of critical whiteness studies have considered writing as a space that could — and this sounds like part of what the essay form already does — ‘retain a faith in the quotidian’.

With this in mind, we should embrace diverse use of vocabulary and not suppress forms of colloquial language that often remain invisible in spaces such as public art galleries and universities. This position is not to be confused with an anti-intellectual polemic against the stylistics of “literary sophistication”, but instead to make a socialist point with regard to the inclusion of various idiolects in coming to an understanding of what writing on photography has been, and might become. Valuable work has been done with respect to language ideology in the field of linguistic anthropology, and the conclusions are not pretty (white dominance; white denials of complicity). Despite what Strunk & White say, and in opposition to what George Orwell would later write in an essay celebrated for all the wrong reasons, Politics and the English Language (1946), let’s forgo the rules. As Kendrick Lamar suggests, ‘build your own pyramids, write your own hieroglyphs.’ Idiolects are, after all, individual, subjectively developed phenomena.

As Elena Gualtieri writes in a discussion of Virginia Woolf, the essay has ‘become in modern times a vehicle of vanity and exhibitionism, encouraging its writers to indulge their taste for a good turn of phrase without providing any food for thought’. This gets to the heart of the essay-gone-wrong (Woolf calls it small-talk); the essay which says nothing, baroque as it stumbles along, drunk and well dressed. Instead, better essays might be conceptually idiosyncratic and simultaneously grounded in research, but they should not reject pleonasm, because we want more than information from language, don’t we? A wide vocabulary is good, when paired with something else substantial (form and substance are chiasmi too). Essays probably should have something to say, even if that something is no particular single thing, more a cluster of apothegms. Images float and the essay floats with them. These issues are far from simple, and politics is never far away when one confronts them.

With the language ideology of writing on photography in mind, I want to call the Strunk & White principles of style — held in such high esteem as they were — white-English-turn-of-the-20C-style. Tight, white sentences. A syntax of privilege. This particular politics of communication requires some sort of counterbalance. In Strunk & White’s discussion of the “necessary” use of definite, concrete language, they assert with respect to canonical writers such as Homer, Dante and Shakespeare that what makes them great is they have the ability to ‘call up pictures.’ Up to where, one might ask? Up to the elite highpoint of literary genius? “Great writers” sit on top of something and call their images up, so it would seem. How can this logic be reversed? It requires an antidote; a clamour of contemporary voices. ‘Nasal voices like a larynx infused with helium’ writes Harris Elliott in his essay Act Like a Wasteman, That’s Not Me (2016), might provide us a counterpoint from which to consider the various voices that constitute the history of writing on photography. In this way, the essay form reaches a heightened pitch at which words unravel into multiple cultural positions. The canon of essays on photography must become more diverse in order to pay homage to the original compositional incongruity of the literary essay, as pioneered by writers such as Virginia Woolf, who wanted essays to be protean and experimental. The form has always strived for stylistic diversity, expansion, multitudes.

When I speak or write, I visualise what I say in something like a series of photographs. But these are not the pictures of Strunk & White. Sometimes, to write personally on the photographic image is to pull down the brick wall of theoretical vocabulary. Or better, to combine flowery vocabulary with the lingua franca of everyday experience. We can have theory chat and literary parlance alongside colloquial speech, after all. This is what Lecercle gets at when he describes the complex ‘temporal layering’ of language, and it is, more generally, what the essay excels in.

Take the photo above. That collection of books in Fox Talbot’s library, they all float around for me, forming a mental image that might be taken apart and analysed through description, association, analogy, even contradiction. In one sense, I must reconstitute the photograph in order to write on it, or write with it, or even through it, as if some tunnel made of paper or pixels. In considering this photograph I can smell dust; I think of, and I see, the books as brown although I know the image is fixed within the muddy tones of its salt-based printing process. They have patina, these books; they appear and are impressed upon me. They remind me of libraries, which are spaces I have never liked, but always liked the idea of. I’ve probably never read any of them, these books. I wonder what they are? What can I do with them, these books I don’t know, in a photograph? Like Strunk & White’s principal elements, the books here are orderly, lofty. When I write about them I want to take them apart and not put them back together as they are. I want to contradict the normative values of description, association: I want to reconstitute this image in order to understand its politics. I want to “call the image down”.

— Daniel C. Blight

Daniel C. Blight is a writer based in London. He is lecturer in Historical & Critical Studies in Photography, School of Media, University of Brighton; visiting tutor in Critical & Historical Studies, School of Arts & Humanities, Royal College of Art and co-editor of Loose Associations, a periodical of new writing on image culture published by The Photographers’ Gallery.

Bibliography

Adorno, T., “The Essay as Form” in Notes to Literature: Volume 1. New York: Columbia University Press, 1991.

Azoulay, A., Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography. London: Verso, 2009.

Baudrillard, J., “Photography or Light Writing: Literalness of the Image” in Impossible Exchange. Trans. Chris Turner. London: Verso, 2001.

Beckman, K. and Weissberg, L., On Writing with Photography. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Blatt, A. J., “Phototextuality: Photography, criticism, fiction” in Visual Studies, 24:2, pp. 108-121. London: Routledge, 2009.

Dillon, B., Essayism. London: Fitzcarraldo, 2017.

Dillon, B., “Photographs” in In the Dark Room. London: Fitzcarraldo, 2018.

Evans, W. cited in Rabb, J.M., “William Carlos Williams: Sermon With a Camera, 1938” in Literature and Photography: Interactions 1840-1990. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995.

Fitzer, L., “Review of Theoretical and Applied Issue in Written Language Expression” in Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 18:1, pp. 203-221, 2003.

Freund, G., Three Days with Joyce. New York: Persea, 1985.

Gualtieri, E., “The essay as form: Virginia Woolf and the Literary Tradition” in Textual Practice, 12:1, pp. 49-67, 1998.

Heron, L and Williams, V., Illuminations: Women Writing on Photography from the 1850s to Present. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1996.

Lamar, K., “Hiii Power” in Section.80 [Sound Recording]. Carson: Top Dawg Entertainment, 2011.

Lecercle, J-J., A Marxist Philosophy of Language. Trans. Gregory Elliott. Boston: Brill, 1996.

Mavor, C., Black and Blue: The Bruising Passion of Camera Lucida, La Jetée, Sans Soleil, and Hiroshima mon amour. London: Duke University Press, 2004.

Orwell, G., “Politics and the English Language” in Horizon, 13:76, pp. 252-265, 1946.

Rabb, J.M. Literature and Photography: Interactions 1840-1990. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995.

Ryden, W and Marshall, I., Reading, Writing and the Rhetoric of Whiteness. London: Routledge, 2011.

Silverman, K. The Miracle of Analogy or The History of Photography, Part 1. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2015.

Strunk, W. Jnr. And White, E.B., The Elements of Style, 4th edition. Cambridge: Pearson, 1999.

Trachtenberg, A., Classic Essays on Photography. New Haven: Leete’s Island Books, 1980.

Willis, D., Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photographers 1840 to the Present. London: W. W. Norton, 2002.

Woolf, V., “Julia Margaret Cameron” in Victorian Photographs. London: Hogarth Press, 1926.