South Africa is my country. But is also my hell.

- Ernest Cole

Below are the longer versions of the text by Ernest Cole from each of the chapters in House of Bondage, as featured in the exhibition Ernest Cole: House of Bondage.

Click on each section below to read the longer texts written by Ernest Cole (unless otherwise stated). Please note: much of the language used is specific to South Africa and the time it was written. Some terms included are offensive today.

Introduction to House of Bondage at The Photographers’ Gallery

This exhibition revisits House of Bondage (1967), the groundbreaking publication by Ernest Cole (1940–1990) that chronicled the brutal reality of Apartheid South Africa. The book was one of the first bodies of work to expose the injustices of Apartheid to the rest of the world.

Born in 1940 in a township in Transvaal, as a young Black man Cole experienced the daily humiliations of the system from the inside. The Bantu Education Act (1953) was introduced while Cole was still in high school and caused him to leave his schooling, instead continuing his education via correspondence courses. His family also suffered ‘forced removal’ from his childhood home in 1960. Cole stated, “Three-hundred years of white supremacy in South Africa have placed us in bondage, stripped us of our dignity, robbed us of our self-esteem and surrounded us with hate.”

In his early twenties, he became one of a small minority of Black South Africans who secured a bureaucratic ‘reclassification’ from ‘Black’ to ‘Coloured’ (also changing his surname from Kole to the less ‘African’ Cole). This meant he no longer had to carry a ‘pass book’ for the authorities to check, could obtain a passport, and work as a photojournalist.

Cole photographed the precarious living conditions of Black South Africans, from mine labourers to domestic workers, as well as the state of the transport, education and health systems. He was one of the first Black freelance photographers in South Africa, documenting everyday life including assignments for Drum magazine and The New York Times, all the while shooting and planning House of Bondage.

In 1966, Cole fled South Africa and smuggled out his photographs, travelling through the UK and Sweden before settling in New York. House of Bondage was published in 1967 and resulted in Cole being permanently banned from his home country.

This exhibition covers all 15 original thematic chapters devised by Ernest Cole in his book. An additional chapter ‘Black Ingenuity’, not published in the original edition, has also been included. Almost sixty years since it’s publication House of Bondage continues to exert an influence all over the world.

1. The Quality of Repression

Today I think the split between black and white in South Africa is irreconcilable. The whites are certain that it is our heart’s desire to be integrated into their society as social and economic equals, but they are wrong. The cruelty of apartheid – separateness – has infected us as well as them: We believe as fervently as they that there should be as little contact between the races as may be possible. For only by a separation more absolute than the most ardent racist could wish does there seem to be a chance of freedom from the suffering and oppression that living beside white men inflicts upon us.

It is an extraordinary experience to live as though life were a punishment for being black. No day passes without a reminder of your guilt, a rebuke to your condition, and the risk of trouble for transgressing laws devised exclusively for your repression. Some of these are merely petty and mean-spirited, others terrible in their severity and injustice. They deny the small comforts of a park bench and a drinking fountain, they make essential permits subject to the caprice of hard-eyed bureaucrats, and they countenance imprisonment without charges, drumhead justice, and political exile.

Legal indignities eventually become part of the reality of your existence – onerous, but unavoidable. What frightens and freezes are the sudden direct attacks on you as a person. The white man’s fear of blackness – and whatever it symbolizes for him – goads him unmercifully. His hatred erupts on slight provocation. One slip, one fancied slight, one ill-considered act or hasty word, and he is upon you, an enemy ablaze with rage and emboldened by his immunity. All blacks have seen white men and women thus. All have been tongue-lashed.

For want of anything else, anger becomes a motivation and a refuge. Superficially you must stay cool, however hard it is to do so. Retribution is swift for cheeky Kaffirs. But inside there is fire. You rise in the morning filled with sour thoughts of your poverty under the white economy. I remember days when I was so broke I could not afford the little gas I needed to go here or there to shoot pictures with the film I nearly starved myself to buy. Whenever I could, I accepted invitations to the homes of white liberals for the food they offered – until it stuck in my throat at the thought of how casually they could regard it.

You may escape, but you carry your prison smell with you. Where parks are free and benches available, you do not want them. Good food does not impress you. Vacations are for fools. You do not try too hard or expect too much of yourself, for it is still a white man’s world and you feel your difficulties are the result of being black. You boldly meet the white man’s eye – and bite your tongue when it slips and calls him baas.

Written by: Ernest Cole

2. The Mines

South Africa’s wealth is rooted firmly in great mineral resources: diamonds, platinum, iron, copper, uranium, and above all, gold. Gold was discovered a century ago and today the ore still pours from fifty-five operating mines. Most of these are located in the Witwatersrand of Transvaal, the ore-rich hills upon which Johannesburg, the “Golden City,” has risen. The mines produce about seventy per cent of the free world’s supply of gold. In 1966, the output was nearly thirty-one million fine ounces worth nearly $1,100,000,000.

I was about twenty at the time, aspiring to be a photographer, but working meanwhile as a layout assistant for Drum, an English-language magazine published in Johannesburg for African readers. Drum was unusual in having a racially mixed staff and widely popular for its exposes of the injustices of apartheid. But the wealthy white South African who owned the magazine also owned mines. Thus, when the editor announced one day that the Chamber of Mines wanted to run an advertising supplement in Drum, we were asked to cooperate.

One day the photographer could not go and I was chosen to stand in for him. We were picked up by a Chamber of Mines official and driven to the WNLA depot. The official conversed easily with the white reporter and ignored me. The labor comes to the WNLA depot, contract in hand, ready to dig the treasure underground. That first day I saw them standing in their patient lines, some queuing up to be fingerprinted, others stripped naked for mass medical examination.

I resolved to learn more about the mines, and in the years that followed I made my way to ten or more big mine compounds in the Rand. Sometimes I made friends with an African guard at the gate who would let me in. Sometimes I showed up so often the guards assumed I worked there. Once in, I was rarely interfered with. To the white guards, as to the mine official, I was just another Kaffir and they paid no attention to me. As a result, I had considerable freedom to see what I wanted to see.

The yard was swarming with African men. There were Zulus, Swazis, Xhosas, airsick Barotses flown in from Zambia in a mining-company plane, Shangaans from Mozambique, and Kwanyamas and Ovambos from South West Africa. All had signed on for a stint in the mines, although not many could read the contract in their hands. Read or not, each man was committed to an initial work period of nine or twelve months.

He would work nine or ten hours a day, six days a week, and his starting pay would be forty-two American cents a day. (That was 1961. Now it is up to forty-six cents a day). The most he could look forward to, after many years in the mines in the highest grade he could attain, was $38, one sixth of the beginning pay for novice white miners.

The African can be discharged, but he cannot quit. If he tries to escape he is branded a deserter and mine detectives from a special squad are sent to track him down. The living conditions of the men who work the mines of South Africa are miserable almost beyond imagining - worse even than in the worst slums of Johannesburg: blank and indistinguishable days, a circumscribed existence, cramped and inward-turning lives. At the end of his contract, the worker can sign on again, this time (and each subsequent term) for six months, or he may go home.

There are also the men who never reach their contract’s end. These are the unlucky victims of mine accidents or of phthisis, a deadly and so far incurable disease of the lungs, which is prevalent among South African miners. In either case the man is returned to the WNLA depot for hospitalization, cancellation of his contract, and discharge.

Written by: Ernest Cole

The Mines (cont'd)

The scale of compensation is frugal. For losing two legs above the knee, and thus his livelihood, one fellow I saw received $1,036, which was being paid out at a rate of $8.40 a month and was supposed to last him the rest of his life. However they leave – sick, injured, worn out, or hale and hearty with the savings of twenty years’ work at $38 a month – they are never missed. For as they go out of the gate, there always are new men coming in.

Written by: Ernest Cole

3. Police & Passes

The standard by which the police operate is cruelly simple: every black man is a criminal suspect. In a technical sense, the police are not far off the mark to be so suspicious. The laws of apartheid are a far-reaching tangle of restrictions, reaching so deeply into everyday life that it is a rare African who does not violate some law.

A typical crime under apartheid relates to the passbook: A policemen may at any time call upon any African who is sixteen or older to produce his reference book. If the African fails to produce it, or if his papers are not in order, he is committing a criminal offence and is liable to a fine or imprisonment. This is the nub of the infamous “pass laws,” a complex mesh of rules and regulations that restrict the freedom of movement of Africans. Compared to some of the other oppressive statutes of apartheid, the pass laws on paper seem modest enough. But in practice they are the keynote on which enforcement of the entire apartheid system is based.

The Government can “pull” a man’s pass at anytime for any reason, or for no reason at all. Simply by “stamping him out,” it may expel him from the city, even if he was born there and has a home, job, and family there. Such a man is “removed” to the tribal district of his forebears, even though he himself has never lived in that district and has no friends there or hope of employment. By keeping him in constant dread of losing his permission to stay, the pass laws succeed in their avowed purpose of never letting the African forget that he “doesn’t belong” in the urban areas. They reduce him to something less than a human being; he becomes merely a unit of labour.

Most pass arrests are made by black policemen; these African cops are resented by urban Africans as much or more than the white ones. If the charge includes vagrancy, the prisoner is in trouble. In South Africa, ‘vagrancy’ is not a minor crime, it means unemployment, or at least the lack of an employer’s signature in the black man’s reference book, and can have serious consequences. When the magistrate sees that a man’s pass lacks the employer’s signature, he demands to know, “How do you live?” If the answer is not satisfactory, the defendant may be jailed for as much as two years, and on his release escorted out of the area.

To avoid this, Africans who are in danger of being arrested often throw their passbooks away. It is better to be picked up for “losing” or “forgetting” your pass than for the unforgivable sin of unemployment.

On any day the prison population of South Africa totals seventy thousand men and women – almost four-fifths of them black. Per capita, almost four times as many prisoners as in the United States. Penalties are harsher, too. In 1965, 124 prisoners were hanged – all but two of them non-white. By comparison, in the U.S. only one prisoner received capital punishment in 1966.

Written by: Ernest Cole

4. Black Spots

In South Africa today a “black spot” is an African township marked for obliteration because it occupies and area into which whites wish to expand. The township may have been in existence for fifty years and have a settled population of twenty-five or fifty or seventy-five thousand people. Nonetheless, if the whites so decree, it can literally be wiped off the map and its people relocated in Government-built housing projects in remote areas.

The Government pays for the property it takes, but the sums are paltry and often tardy in coming. Sophiatown, a lively center of African life and home-ownership in Johannesburg, was bulldozed into a flat expanse of rubble. The new white township that went up in its place was called Triomf. Afrikaans for “triumph.”

One morning in 1960 the Government bulldozers came clanking down the road into the neighborhood where I lived. This was in Eersterust, a black freehold township ten miles east of Pretoria. Some would call it a slum and parts of it deserved the label. But I loved Eersterust. Our house was not fancy, but it was built of brick and had six rooms. I had lived most of my twenty-one years in that house, in that neighborhood. My father, a self-taught tailor, and my mother, a washerwoman, had raised their six children in the house. Most important, we owned the buildings and the land beneath them. In fact, the property had been in my mother’s family for half a century, since 1910. This was no mean achievement for an African family. The property represented the labor and savings of several lifetimes. To us it was a proud heritage.

Once the bulldozers began their work, they were quick about it. Within minutes the black spot had been eradicated. Our neighborhood was rubble, our house a pile of bricks. For our heritage of half a century we were paid $840. My family, along with all the belongings we could carry, moved to Mamelodi, a new black “location” which the Government had put up on the far eastern-edge of Pretoria. We were renters, now. The privilege of owning land was forever lost to us. We had been poor before. We were poorer now. The Government had put a roof over our heads and, by its own reckoning, owed us nothing more. The houses were incomplete and soon began to crumble. The four small rooms had no doors, no plaster, and dirt floors. There was no running water; it had to be fetched from a tank in the street.

Toilets were outside and used the bucket system. The stench was suffocating. The destruction of Eersterust had smashed the relationships we had enjoyed with our neighbors. Friends of many years’ standing went out of our lives, for in Mamelodi we were not permitted to settle down with neighbors of our own choosing unless they happened to be of the same tribal background.

In time we rebuilt our lives. But it was never the same, for with Government housing came Government supervision.

Written by: Ernest Cole

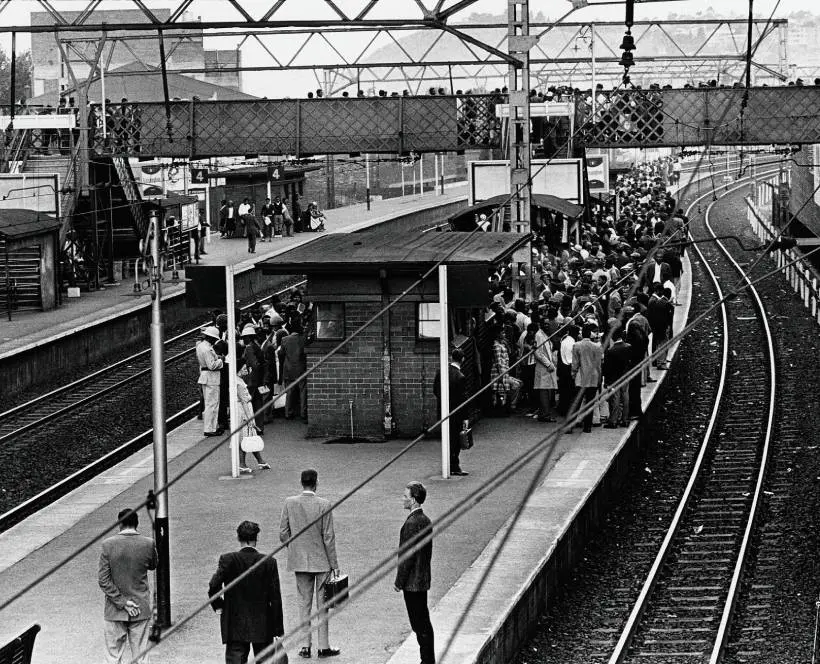

5. Nightmare Rides

Getting to or from Johannesburg by railroad is a nightmare if you are black. Trains are too few, too full, too slow. Some African commuters must leave home as early as 5 a.m. to be sure of reaching their city jobs by 7:30. Some are unable to catch a train back to their black township before 7 at night. These people may never see their homes in daylight, except on holidays. Twice each day, at the morning and evening rush hours, the segregated station platforms are a bizarre sight. At one end, a few white travelers stand about, surrounded by space. At the other, a dense mass of Africans is congregated, crowded and compressed.

Finally a train pulls in and the doors open. If it is a white train, the few white passengers step aboard leisurely and choose a seat, for perhaps eight of the eleven cars will be exclusively for them. If it is to or from a black township, all cars will be for Africans, but always they are jampacked and always there are far more people than even the most congested cars can hold.

Within seconds the cars are full – every seat, standing room, even the overhead space where passengers literally hang from the rafters. Dozens of others have crowded onto the couplings between the cars or cling to precarious hand- and footholds on the outside. “Washing” they call it.

For when a train goes by at speed these passengers look like clothes hanging on a wash-line. It is no exaggeration to say that this wash hangs on for dear life. In one recent year, about one hundred and fifty Africans were killed riding the Johannesburg trains alone.

Africans have become commuters more by law than by choice. The law requires non-whites to live far from the white residential and business areas where most of them work. The idea is to keep the black population out of the city environment, but not so distant as to reduce its effectiveness as a labor force.

The nightmare rides that the African endures not only sap his strength but strip him of individual dignity. Yet as a disenfranchised sub-citizen he has no recourse. Unlike so many lands, where public transportation operates at a loss and must be heavily subsidized, South Africa’s black-supported railroads cost the taxpayer nothing. Instead they turn a profit of $10,000,000 a year for the white Government.

Written by: Ernest Cole

6. The Cheap Servant

White homes are the crucible of racism in South Africa. Here the races meet, face to face, as master and servant. But unfortunately they do not mix. Nowhere is there more animosity than in the everyday relationships between household domestics and their employers. The Africans, for their part, are bitter over what they consider to be degrading treatment and poor pay. The whites are baffled when servants seem lazy, resentful, and ungrateful. White women, particularly, spend hours conferring among themselves on the problem, apparently beyond their powers of comprehension, of how to “handle” their servants.

Needless to say, all servants under discussion here are black and all masters white. I have never seen or heard of a white servant in South Africa. Black help is abundantly easy to come by. In Johannesburg alone, there are seventy thousand black servants. Even a Boer of the poorest white class, a railway line worker, for instance, will have a servant. On the job he may only be a laborer, but at home he’s somebody’s boss.

Pay, pay, pay. That is the basic issue. There is hardly an employer who does not take advantage of his help. Typical pay for a live-in servant is $15 to $20 a month, plus bed and meals. A few earn more. Many earn less. The employer’s attitude is, “I feed you, I house you. You have no other responsibilities, so what more do you need?”

It is a wry joke among Africans that, for all the practice they get and the time they devote to talking about it, white masters and madams still don’t know how to deal with their black help. The trouble usually is that the employer insists on treating the African as a subhuman being, devoid of feelings. What is your madam like, I asked one experienced cook. “Rude, raw, and impossible from the core,” she said. “And hard to please. Whites think that with their money they can buy everything, even your feelings.”

In the long run, the employer pays a price for the shoddy treatment and low pay he dispenses. Little or no sense of loyalty develops between servant and master. One of the ironies of the system is the role of the black nanny. The visible affection that flows both ways between a nanny and the white children in her care can be a wonderful sight to see.

But even that relationship is doomed. Home after all is the incubator of racism. Children watch how their parents treat the black “boys” and “girls” and soon the youngsters realize that they can get away with the same conduct. Servants obsequiously call the children klein baas (small boss) and nonnie (small madam). The kids soon get to like this. The lessons they learn at home are carried into the streets, into offices and factory and Government post. Thus the awful heritage of racism is perpetuated.

Written by: Ernest Cole

7. For Whites Only

The infectious spread of apartheid into the smallest detail of daily living has made South Africa a land of signs. They are everywhere, written in English or Afrikaans or in a local native dialect as the situation may require. But always their purpose is the same: to spell out the almost total separation of facilities on the basis of race. Until recently the signs used the euphemism “Europeans Only” or “Non-Europeans Only.” Now as the Government seeks to emphasize South Africa’s own heritage, independently of its historic European ties, the wording of the signs is changing to “White Only.”

The signs point to racially segregated public toilets, to drinking fountains, phone booths, and station waiting rooms (where only one of anything has been provided, it is, of course, White Only). Post offices are marked with separate entrances leading to segregated windows for selling postage stamps. Parks are often reserved for whites only. Those the blacks may visit have white-only benches. The African who wishes to rest must sit on the curb.

At the blood bank, black and white plasma is kept carefully separated, although in an emergency the doctor would not hesitate to use whatever blood is available because, chemically, there is no difference in the blood of whites and blacks. (He’d never tell the patient, of course.)

The temptation is strong to tear down the signs or deface them. (One trick guaranteed to cause confusion is to alter a sign that reads “NonWhite” by scraping off the “Non.”) But in South Africa it is a serious offence to damage the signs of apartheid. The offender may be fined or jailed or even whipped.

Written by: Ernest Cole

8. Below Subsistence

In the midst of South Africa’s abundant economy, forty-five per cent of the black families live on incomes below the subsistence level. We call it living “below the bread line,” living on less than the bare-bone minimum of food, shelter, and clothing required to keep a person alive and moving. A survey made in 1959 concluded that a South African family of five needed a minimum monthly income of $77, without provision for medical care, education, furniture, or holidays. Inflation has been fierce since then, so that the minimum has gone up, but the African has only been left farther behind. His average family income is barely $50 a month.

One popular myth is that Africans can live much more cheaply than whites. That’s a bad joke. A saying in the township goes: “We are paid as Africans but we have to buy as white men.” Food costs no less for the African.

Most non-whites live in a chronic state of partial starvation. They cannot afford to buy enough of even the plainest food to properly sustain life. The result is widespread malnutrition, sickness, deformity, and death. One black infant in every four dies before its first birthday because its mother cannot provide the necessary food and hygienic surroundings to keep it alive. One half of all black children die before they are sixteen.

Along with hunger and disease, another sure by-product of artificial black poverty is crime. It takes only simple arithmetic to figure that if a family’s income is below the bread line, and yet the family survives, it must be making up the difference somewhere. The answer too often is petty thievery: shoplifting, stealing from an employer’s home or his warehouse. It is one more little irony inflicted on the white master that he must live surrounded by thieves and can trust no one. But he must ask himself, how else his underpaid employees stay alive? Of course small, silent crime can expand, often merely by accident, into big, bloody crime. As one hard-pressed family provider told me, “When the struggle gets too savage, you must become savage, too.”

One afternoon in Mamelodi, one of the large townships of Pretoria, I saw a little girl who couldn’t have been more than six. She was carrying a baby sister on her back. Children caring for children is a common sight in township streets, but I watched this one, bowed under her load, wander over to a ramshackle house and hand the baby, who was crying now, over to an older girl, who looked as though she should have been at school. “What are you doing home?” I said, somewhat severely, because many children stop their schooling before they should. “I have no proper clothes for school,” she said, and began to cry.

Her name was Grace Matjila. She was ten years old. Because of her ragged condition she stayed home and “baby-sat” for her little sisters. In effect, Gracie’s childhood was over.

Written by: Ernest Cole

9. Education For Servitude

“When I have control of native education,” said Dr. Hendrik F. Verwoerd in 1953, “I will reform it so that natives will be taught from childhood to realize that equality with Europeans is not for them.”

Under the Act, the Minister explained, the Bantu would be given no more education than he needed to perform his menial function in the South African economy. “It is of no avail for him to receive a training which has as its aim absorption in the European community … What is the use of teaching a Bantu child mathematics when it cannot use it in practice? … That’s absurd.” The child simply grows up to be an “imitation European.”

Each days some two million young Africans, neatly turned out in the compulsory uniform of white shirt and black pants or jumper, enter segregated Bantu schools to be educated for servitude.

Writing, music, and simple hygiene are among the primary subjects taught, although the schedule permits no more than twenty minutes to be devoted to each one. In such conditions learning occurs by accident, if at all. “It’s impossible to hold the children’s attention,” one teacher told me. “In a very full class I cannot even walk through the room to get to those in the back. I would have to climb over children who are sitting on the floor and in the aisles.”

School is not compulsory for Africans, nor is it free. A tuition fee is charged. Pencils and paper are extra. Uniforms, too. The typical hand-to-mouth African family must sacrifice to pay for even this rudimentary education of its children. Conditions at home may combine with conditions in the classroom to encourage truancy and dropping out. If there is no money for school fees or no parent at home to enforce attendance, a youngster’s schooling may halt when he is nine or ten.

There are three tribal colleges for blacks, controlled by the Government, administered by whites, and located only in the Bantustan reserves. Academically, they are little better than high schools, although even at that they are short of qualified applicants. From these emerge the few black lawyers, teachers, social workers, and professional men permitted in South Africa’s closed society.

There is a subtle difference between discriminatory education under the British and that under the Afrikaners. The British, and the succession of pro-British Governments after Union, were not any more eager to educate the black man than the present Government, although it might have seemed that they were because they encouraged the African – and themselves – to believe that in a misty, future Someday there would be a multiracial South Africa with equality for all. Educated blacks were a token of that promise, but too many of them would have been intolerable. So there were fewer schools than there are today, and fewer children in school, although the school day ran full time and the intellectual level was higher. The Afrikaners, of course, want a South Africa in which there is no future for blacks, except in Mr. Verwoerd’s terms.

Written by: Ernest Cole

10. Hospital Care

Most Africans are treated by white doctors at public outpatient clinics in the black townships, or at one of the provincial hospitals designated for them.

Everyone would go elsewhere if they could. Africans approach the clinic with reluctance, the hospital with fear. This is because every African knows the ordeal that lies ahead of him when he seeks medical treatment. It is like going to prison, except that the hospital may be worse.

The wards are so jammed that newcomers must sleep on chairs, or on felt pads on the floor. The white chief administrator of one large African hospital; was quoted as saying: “Natives prefer to sleep on the floor.” Hardly so, although it might be true in hospitals I have seen where mattresses are blood-stained and sheets not changed between the departure of one patient and the arrival of the next. The food is meagre and disgusting. It is barely edible. I have choked it down and I know.

Nursing care is minimal, grudging, and callous. This shocks many patients, for the nurses are themselves Africans. But it is a sad business, nursing. The girls are undertrained and overworked. The preparation they get in their segregated schools is inferior to that given white nurses. They learn nothing of the psychology of nursing, nothing of human relations, nothing of the special needs of patients. They observe the doctors’ brusqueness with their cases and soon learn to act the same way.

My own introduction to hospitals came a few years ago, when I was involved in a motorbike accident in downtown Johannesburg. The time was a few minutes after noon on a Saturday. Both my legs seemed to be broken and I could do no more than pull myself to the sidewalk and sit there. Police came to investigate. Two and a half hours later an ambulance came and picked me up. Eventually we were taken to Johannesburg General. This hospital has two sections, for black and for white, and at that time was used mostly for emergency cases. A doctor there declared that both my knees were shattered and I would have to be admitted to a hospital. But not Johannesburg General. I was left on a stretcher to “wait for transport,” as they say, until another ambulance came for me. This one took me to Baragwanath.

The following Friday – six days after my accident – I was operated on. The orthopedic surgeons operated at Baragwanath but once a week. Altogether I was in the hospital for twenty-six days. It was long enough to educate me. Most of that time was spent in a so-called convalescent ward. The nurses had a more accurate name for it: the “dumping ward.” They dumped you there and forgot you until they were ready to operate, or until you were well enough to go home.

The first day that I could walk again I walked out of Baragwanath. But I went back, many times, to that hospital and to others. Sometimes I just walked in during visiting hours with my camera concealed. Other times I slipped in after hours, dodging the guards who did not want stories published about the hospital and who would stop and search anyone they suspected.

Written by: Ernest Cole

11. Heirs of Poverty

The streets of Johannesburg, Pretoria, and the rest are overrun with little African boys who have left home to make their own way. “City orphans” we call them. There are so many of them that they are unremarkable, commonplace, a part of the landscape. Some are as young as seven, but most are ten or twelve. They drift through the streets in small packs, like rubbish blown by a breeze. Their clothes are ragged, their bodies undernourished. And they beg from whites.

“Please, baas, penny. I hungry. Please, baas.” Some whites reach into their pockets and impersonally toss a coin or two. Others brush by. Once in a while, a choleric man will cuff a boy for displaying his misery so openly and without shame. The slap will sting, but the rebuke is meaningless.

In a few years, the boy very likely will become a tsotsi – a tough teen-age delinquent – living on the proceeds of thievery, assault, and any other low-grade criminal opportunity. Tsotsis take their name from the U.S. zoot-suiter of a generation ago, and they act the part. They are the street-corner dandies, lounging in the doorways of vacant stores, idling in the train stations and bus terminals, giving passersby the hard eye. They are the scourge of the black townships, where there is no police protection, and their own people, therefore are the easiest and most vulnerable targets. The weekend is their favourite time for robberies, muggings and knifings. Slashed victims may be seen at the hospitals and clinics any Friday or Saturday night. The police don’t care as long as whites are not attacked. “Just Kaffirs killing each other,” I have heard investigating officers say. “It doesn’t matter.”

They lived very well by stealing from black and white alike, although they preferred the white pigeon. “These whites carry money and lots of it,” one young pickpocket explained. “Their pocket money is enough to pay you or me for a year in a regular job. I can’t see the sense of working six days a week for a white man and have him give me an envelope [an empty pay packet]. I can steal many times as much in six seconds.”

The pickpockets may operate alone or in teams. They are uncanny in their ability to spot who has money and where it is being carried. Their methods vary. One approach that works well is to walk up to a white man and chuck him insolently under the chin. People outside of South Africa have no idea how infuriated a white man can get from being touched in any way by a black. The tsotsis know that in his rage he won’t even feel the wallet being lifted from his back pocket by a confederate.

Criminal life admittedly is dangerous, but the rewards are tempting and, anyway, what has an African got to lose? For the whites, the only refuge is behind the steel bars at their windows, the only security in private watchmen and a revolver by the bedside. It is their purgatory that they must live their days in an armed camp, under a siege of their own making.

Written by: Ernest Cole

12. Shebeens & Bantu Beer

Two kinds of drinking are found in South Africa today: legal consumption of brandy and Government-produced Bantu beer in barren, city-run beer gardens, and illegal drinking of hard liquor and strong beer in privately run hangouts called shebeens.

The shebeens came first, in reaction to the “European” prohibition against African drinking. Actually, the African’s taste for drinking was well developed long before he came into contact with the white man. Drinking of homemade beer was an integral part of the religious, social, and economic life of old tribal Africa. But for the most part the African took his drinking casually. The concoctions he brewed for ceremonial use from cereal, fruit, and honey were mostly mild and rarely made him drunk.

It is not surprising that prohibition proved no more enforceable in South Africa than it has anywhere else. Shebeen operators managed to stock their speakeasies with bonded “European” whiskey and brandy acquired, at a price, from white boot-leggers. Raiding police broke up hundreds of shebeens, at least temporarily, poured a tidal wave of illicit hooch into the gutters, and arrested thousands of otherwise law-abiding Africans. But they failed to stop the drinking.

White South Africans, whose own social drinking is carried on without legal handicap, or any other noticeable restraint, professed a highly moral attitude toward African drinking. Under the guise of “protecting the native from himself,” they voiced disapproval of the admittedly shabby and loosely run shebeens, where the old tribal etiquette of separate drinking for men and women was violated, where pickups could be arranged, and children were idle spectators of their parents’ behavior.

Beginning in 1938, South Africa’s white-run municipal governments plunged into the beer business. City-run breweries, using old tribal recipes much like the ones that had been forbidden for home use, began producing vast quantities of so-called Bantu beer. It is thick, sourtasting drink, purplish in color, and containing only a piddling two per cent of alcohol.

Prohibition on hard liquor ended in 1962. Since then, Africans over eighteen have been permitted to buy liquor and beer-to-go in bottle stores. There now are bar-lounges, as well, where an African can buy liquor by the drink. Like the beer business, bottle stores and lounges for Africans are a Government monopoly.

Despite the end of prohibition and the appearance of Government-sanctioned drinking establishments, the urban African still takes much of his business to his favorite, unlicensed, illegal, friendly neighborhood shebeen. Perhaps it is the feeling that this is his sanctuary, a place where he isn’t feeding the Government coffers every time he buys a drink, a place where he can sit at ease among his own kind and talk, drink, and be himself.

Written by: Ernest Cole

13. The Consolation of Religion

From the start, Christianity in South Africa has stumbled over the color line. Long before Government apartheid came into force, missionaries dispatched from Europe and the United States were preaching separation within the church. The only way the new African Christian could fully express himself would be within an all-black congregation.

The extreme position, and unfortunately a most influential one, is held by the Dutch Reformed Churches. The Dutch Church teaches apartheid as an integral part of Christianity. Its Golden Rule is that there is no equality between black and white in church or state.

Today’s black Christian wonders why his church remains so quiet on the subject of apartheid. Sunday preachers generalize about social justice, but they rarely bear down on the specific injustices their parishioners suffer day after day.

Many more Africans, especially the poor and the poorly educated, merely give up “white man’s religion.” They turn instead to other forms of worship that they find more gratifying. There are three categories of these: 1) the Ethiopian movement, 2) the Zionists, and 3) the return to ancestor worship.

The new, all-black, independent Christian churches were greatly influenced by the mission churches from which they sprang. But they refused allegiance to any European source of authority. Instead, they espoused the Ethiopian line, which at its simplest, is Africa for the Africans.

As a synthesis of the old ways and the new, Zionism offers the African many pluses. If a man is ill and the white man’s medicine does not help him, he may go to see the unlicensed tribal doctor without offending his church. The faithful take vicarious satisfaction in the opulent living practiced by the more notorious black clergy, probably because they are glad to see at least one of their own kind get ahead.

Before Christianity came to Africa, people believed that the spirits of their ancestors controlled their daily lives. The first of three general categories of medicine man is tthe Rainmaker, a function that always has been considered vital in rural Africa’s crop-and-cattle economy, which is perpetually endangered by a shortage of rainfall. Second is the Herbalist, a sort of general practioner who handles routine disturbances, such as contention in a family, money worries, and minor illness – including what white hospitals call “Kaffir poison,” a physical and psychological malaise that resists Western-style treatment.

If the bones indicate that the patient suffers a tormented spirit, such as Western medicine might diagnose as requiring psychiatric treatment, the case is beyond the Herbalist’s competence and he passes it on to the third and most potent category, the diviner.

One branch of Christianity that continues to make substantial numerical gains in South Africa is the Roman Catholic Church. The Catholics push hard on a grass-roots recruiting program. The priest in my own township increased his congregation from two thousand to six thousand in about five years. One reason for the Catholics’ success is that they preach nonracialism. The Catholics have their own problems, however. Their schools and seminaries have always been segregated. Until recent years, most orders of priests and nuns were closed to Africans.

At the township level I have observed a number of young priests and ministers who realize that the Christian church must roll up its cassock sleeves and work directly to improve the lot of the people in this life, as well as the next, in the earthly houses of God as well as in heaven.

Written by: Ernest Cole

14. African Middle Class

At the peak of the black population structure of South Africa there is a relatively privileged group that can be called middle class. The economically well-endowed include doctors, lawyers, merchants, storekeepers, and most likely some shebeen owners and other operators on, or over, the edge of the law.

The marks of their success are modest: a better home than the Government-built matchboxes of the townships and on a better plot of land, a car – sometimes an expensive one, decent clothes, a glow of health and wellbeing that comes from adequate diet. Some families have inherited old tribal wealth. Others are the descendents of mission-trained Africans and have known education and middle-class values for three or four generations.

When the white encounters independence or ambition in a black man he is surprised and offended. To attempt to improve oneself is simply being uppity, a form of misbehavior. “What right have you got to rise up?” he asks irritably. Ironically, as far as they are able, middle-class African families will try to behave like the English, copying their dress, their conversational quirks, their mannerisms, and the way they raise their children. The resemblance often is close, except that no amount of posturing can obscure the fact that they are black.

Perhaps most poignant is the effort to cross the great chasm and make friends with whites. A few churchmen, a few liberals, a few fellow members of a few biracial organizations will invite blacks to their homes for tea or tennis or dinner. There is little to be gained, except in terms of status. Gratitude for being welcomed across the barrier can lead to conviction that the leap has been made not symbolically or experimentally, but on merit, and the pursuit of invitations and the cultivation of white friends may become almost a way of life.

False values and muddled objectives have not only confused middle-class Africans socially, but weakened them as a political force and as a source of political leadership. Because of their emotional alliance with whites, they have compromised their own effectiveness. Today there is simply no role for middle-class Africans to play as mediators or peacemakers or exemplars or forerunners in leading the blacks out of bondage.

Written by: Ernest Cole

15. Banishment

Banishment is the cruellest and most effective weapon that the South African Government has yet devised to punish its foes and to intimidate potential opposition. Its legal base is a forty-year-old law, the Native Administration Act of 1927. This law empowers the Government, “whenever it is deemed expedient in the general public interest,” to move any individual African, or an entire tribe, for that matter, from any place within South Africa to any other place. In effect, this means that any African suspected by the white authorities of being, or thinking about being, a troublemaker can be summarily taken from his home and banished to a remote and desolate detention camp. No prior notice is required. No trial is necessary, no appeal possible, and no time limit set. Banishment can stretch into eternity.

Since 1950 when the current Nationalist administration began implementing the law, some one hundred and forty African men and women have been banished. Most of them once were tribal chiefs, village headmen, or simply men with leadership qualities – in short, influential men whom the Government would wish to neutralize.

Today between thirty-five and forty Africans are still in banishment. The number is small; the enormity is that banishment can happen at all. Not many people are aware that it does. The only official recognition that the banished even exist is a list of their names pasted once a year in the House of Parliament. The banishment camp I selected was Frenchdale, an isolated outpost in the northern reaches of Cape Province, near the border of Botswana, reputedly the worst in the system. I made my trip in 1964, driving from Johannesburg.

When we eventually arrived at Frenchdale everybody in the camp came together to greet us. They were so glad to see us, to see anyone. There were six inhabitants – five men and one woman. The youngest was in his thirties. The others were much older. For five days and nights I stayed with these people. I shared their cook-fires and slept in their huts. As I listened to their stories, I got to know something of their feeling of emptiness.

The huts of the banished had dirt floors, concrete walls, and thatch roofs. There were no lavatories or baths, and no electricity. The only light was the feeble glow of a tiny paraffin lamp with a wick of string. The nearest water was three-quarters of a mile away, and early each evening, as coolness crept over the land, a trek was made to fill the water cans for the next day.

Aside from rare and bittersweet visits from relatives, the banished are almost entirely cut off from society. The Government’s lack of interest is profound. There have been cases when the officials in charge have not known whether a man had been released or was still vegetating in a camp.

Drowning in dullness, once-keen intellects rehash old grievances and engage in old arguments. For the banished an infinity of unremarkable days stretch ahead.

Written by: Ernest Cole

16. Black Ingenuity (written by James Sanders)

Ernest Cole appears to have prepared a tentative section for House of Bondage, loosely titled “Black Ingenuity.” Although we do not know why he abandoned plans to include the chapter, he gathered the contact sheets together into a similar grouping to the other chapters and marked a number of images for inclusion. “Black Ingenuity” examines the possibilities for black cultural production while also mourning apartheid’s suffocation of such spaces.

Historian Jacob Dlamini challenges the facile idea that “black life under apartheid … existed as one vast moral desert … as if blacks produced no art, literature, or music” in his book Native Nostalgia (2009). He explains, quoting cultural theorist Svetlana Boym, that reflective nostalgia “lingers on ruins, the patina of time and history, in the dreams of another place and another time.”

Ernest Cole in his intuitive way is trying to say something similar by concentrating on Dorkay House, the fabled home of the African Music and Drama Association and the Union of South African Artists. Cole is determined to acknowledge the Drum magazine moment in South African cultural history.

Cole was particularly attracted to areas of creativity that had been undervalued or dismissed by white audiences. I think it is fair to say that photography itself was one of those nodes of creativity – junction points in the popular arts. Some spaces of opportunity were undoubtedly in the sporting arena although Cole only devotes a small amount of his visual assessment to boxing and completely neglects football, which was, as now, particularly popular with black supporters.

Cole is insistent on portraying his subjects in acts of volition, creating and consuming black culture. The musicians, for example, are full of agency. The studious pianist is not merely performing or practicing, he is composing, writing music. Gibson Kente is directing actors and dancers in the rehearsal spaces of Dorkay House. The audience at the 1964 Castle Lager Jazz festival in Johannesburg’s Orlando Stadium, organized by Union Artists, is generous and celebratory as they acknowledge the groundbreaking talents of the Malombo Jazzmen.

Yet Cole is equally careful to expose the limits of black creativity – how easily black ingenuity can be manipulated, extinguished, or turned into an instrument of oppression. Cole seems particularly interested in how the black body is represented and who are the consumers of that representation. He demonstrates and challenges black culture as a space for agency in his pictures of the shoppers for African art who are primarily white, and shown both in an attitude of disdain and admiration. Cole’s portrayal explores the threat of stereotyping and marginalization by the dominant white marketplace.

Perhaps it is no surprise that Cole opted to drop the chapter. In 1967, it was difficult enough to tell the visual story of apartheid without opening the reader up to a nuanced, sophisticated understanding of black cultural production and representation and the inherent contradictions of black life in South Africa.

Written by: James Sanders

Ernest Cole: House of Bondage is realised in collaboration with Magnum Photos. Curated by Anne-Marie Beckmann and Andrea Holzherr, and adapted for The Photographers’ Gallery by Karen McQuaid, Senior Curator.

This exhibition is supported by Cockayne Grants for the Arts, a donor-advised fund held at The London Community Foundation and Gerry Fox.

In 2022, House of Bondage was re-released by Aperture with an additional chapter. The book is available to buy in the Gallery bookshop.

A selection of materials from London’s Anti-Apartheid protests, drawn from The Bishopsgate Institute Special Collections and Archives, is also on display on the 4th floor.

Explore more of Ernest Cole's work in Ernest Cole: A Lens in Exile at Autograph. The first exhibition of Cole's photographs documenting New York City during the height of the civil rights movement in America. Now on until 12 October 2024. autograph.org.uk Tube: Shoreditch High Street / Old Street