"Seeing symbols of my own culture in an art institution – which I yearned for during my adolescence and adulthood – was a moving moment."

– Zula Rabikowska

Polish is now the second most spoken language in the UK after English, but when my family and I first moved to the UK in 2001, being “Polish” carried very different connotations than it does today. We left Poland after a decade or so after the Berlin Wall came down. Poland was emerging from the post-communist hangover, and many people were leaving the country in search of a more promising future. The decision to leave Poland was not my own; we followed my mum’s academic work abroad. She spoke English, but my sister and I arrived without a word of it, clinging onto the language of our Slavic ancestors.

We first moved to Glasgow, and at the time, many people couldn’t even locate Poland on a map. My classmates associated it with huskies, wolves and the North Pole, while older generations held onto Cold War-era images of Soviet shortages, harsh winters and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. After Poland joined the EU in 2004, Polish people quickly became the punchline of jokes about plumbers, fruit pickers and other so-called undesirable jobs. By 2016, during the Brexit referendum, Poles were turned into convenient scapegoats in anti-immigration propaganda. Many globally acclaimed figures of Polish origin are still rarely recognised as such – among them Copernicus, Maria Skłodowska-Curie, Chopin, Joseph Conrad and Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit.

Growing up in the UK, I rarely saw cultural references that reflected my own experience. The 2025 UK-Polish Season celebrating Polish culture across the country, felt like something the Polish diaspora in the UK has been waiting for. The first decade as an immigrant, especially when you are learning the language, can be deeply isolating. When we first moved, it was pre-social media, pre-WhatsApp or budget flights to Europe. Upon our arrival, we lacked a community we could connect with, we didn’t have a support system and there was no representation of the Polish experience in any media, school syllabus, let alone art and culture. At Easter we painted eggs and carried salt, ham and horseradish to a nearby church, which raised many eyebrows from locals, especially as this was before we moved to London. Our lunchboxes were often filled with gherkins, pickled herring or an occasional beetroot soup, which proved to be prime material for bullies, which sometimes turned out to be classmates, at other times teachers. This was before the appearance of the soon to be beloved Polski Sklep, so when in the run-up to Christmas, we tried to find somewhere to buy carp (preferably still alive), butter beans, or hay to put under our Christmas plates, shopkeepers were left startled by our bizarre requests. As a child and teenager, and later a young adult in the UK, I observed an ongoing lack of representation of the experience that I was having.

The UK-Poland season brought with it a wave of art commissions, exhibitions, performances and community events – moments of visibility and recognition that have long felt overdue. Among them is Zofia Rydet’s retrospective at The Photographers’ Gallery, a landmark exhibition honouring one of Poland’s most significant photographic voices. Seeing symbols of my own culture in an art institution – which I yearned for during my adolescence and adulthood – was a moving moment.

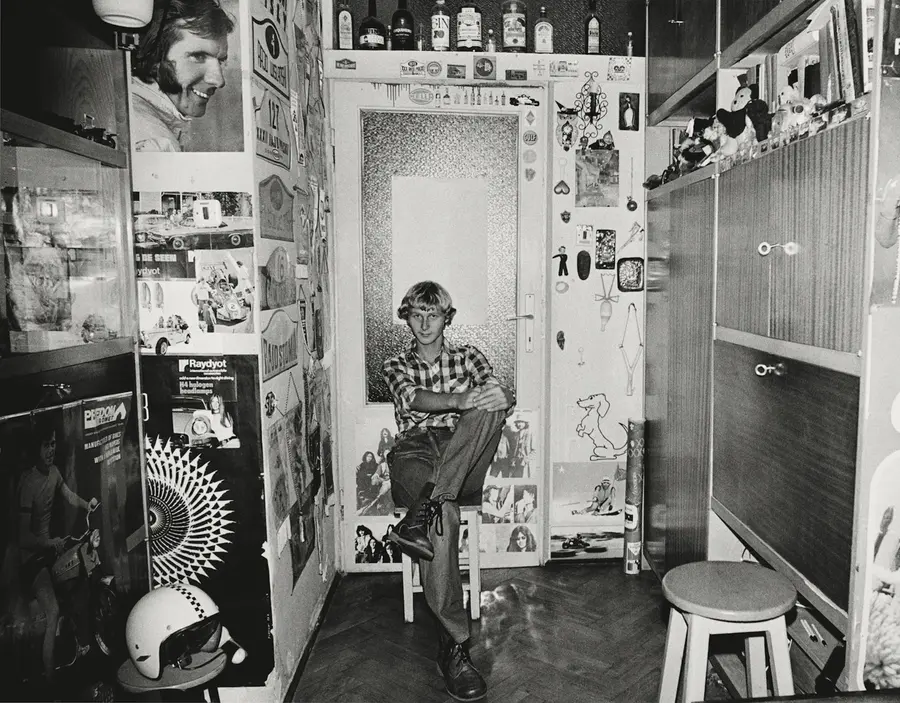

Rydet is best known for The Sociological Record – an extraordinary lifelong project documenting thousands of domestic interiors and portraits across Poland from the late 1970s onwards. Her work captured the nuances of everyday life during a time of rapid social and political change, revealing how identity, class and belonging were expressed within the home. For me, Rydet’s photographs are a commentary on a particular period in time, a transition from communism to capitalism, a shift from rural to the urban and a way of seeing that span the personal and the collective.

In the context of the UK-Polish Season, her retrospective feels particularly relevant - a moment to reconsider how Polish culture is represented, both within Poland and abroad. Attending the opening at The Photographers’ Gallery was a particularly meaningful experience – Polish was being spoken, journalists from Polish media were present, and I met colleagues and peers from across the industry who were interested in Polish history and culture, not something I have experienced outside of very niche audiences. It was invigorating to hold conversations in Polish within a major art institution, a space where I usually navigate my professional life in English. Seeing Rydet’s black-and-white photographs offered a way to embrace my duality as a Polish immigrant in London. Though her images depict a version of Poland that no longer exists, their recognition feels vital – a bridge between memory and the present.

I discussed Sociological Record with my mum who also visited the exhibition. We were both deeply moved by the large vinyl image of a straw house surrounded by smaller photographs of other homes. It is heartwarming to see such intimate, everyday experiences documented and acknowledged in the Gallery – moments that resonate deeply with many Polish people living in the UK.

The recurring presence of John Paul II in Rydet’s work also struck a familiar chord; his image continues to appear in Polish households both in the UK and in Poland, carrying with it layers of cultural memory, belonging, but also conflict. Some of Rydet’s portraits – with their lace curtains, tablecloths, patterned rugs and carefully arranged family photographs – reminded me of our own home in Poland. They share an aesthetic and emotional language that feels instantly recognisable: the way ancestors’ portraits watch quietly from the walls, the mix of pride and modesty in how people present their space. To see this visual culture acknowledged and valued within a major British art institution feels both affirming and long awaited – a recognition of a Polish history that has long existed yet has rarely been seen.

My migration journey is at the crux of my personal identity and professional practice. Living between two countries, languages, histories and cultures has shaped how I see the world, and consequently how I am sometimes othered. Whether that’s because of my name, accent or cultural traditions British and Polish society demand to know where I am really from. A lot of my work stems from trying to locate Eastern Europe, exploring borders and a yearning for home.

Living and creating within this liminal space inspired me to seek out other artists who share similar experiences. From this desire for connection and dialogue, the Rethinking Eastern Europe Collective emerged. I founded the collective to challenge outdated perceptions of “Eastern Europe” and create space for more nuanced stories from the region, where artists can exhibit, screen films, enter into a dialogue and contribute to a knowledge exchange. What started off as a pop-up one-day exhibition in the Photo Book Café in May 2024, is now a collective of 50 members from 20 different countries in Central and Eastern, as well as the Balkans, the Caucasus region and various diasporas and artists who reside internationally and make work linked to the region.

The UK-Poland Season and Zofia Rydet’s Sociological Record offer a hopeful sign of change – a reminder that Polish voices and experiences are becoming an integral part of the UK’s cultural fabric.

Get to know Zula Rabikowska

Zula Rabikowska is a London-based documentary photographer, videographer and artist exploring themes of migration, identity, and LGBTQI+ communities. Drawing on her Polish heritage, she creates intimate, community-based portraiture and collaborative projects across Europe and the Balkans. A member of the Association of Photographers and Women Photograph, her work has been exhibited internationally and published by outlets including BBC, BJP, The Guardian, and Rolling Stone. She is also a co-founder of Rethinking Eastern Europe Collective and lectures photography at Kingston University.

Website: https://zulara.co.uk/

Zula Rabikowska IG: https://www.instagram.com/zula.ra/

Rethinking Eastern Europe Collective:

www.instagram.com/re.thinking.eastern.europe/

Zofia Rydet: Sociological Record is part of the UK/Poland Season 2025. It is co-curated by Karol Hordziej and Clare Grafik. It is produced by The Photographers’ Gallery in partnership with the Adam Mickiewicz Institute and the Zofia Rydet Foundation. UK/Poland Season 2025 is organised by the British Council, the Adam Mickiewicz Institute and the Polish Cultural Institute, financed by the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Poland.