"I chose to focus on ordinary, everyday scenes and the search for formal solutions to translate this mundaneness into photography."

Boris Mikhailov [1]

Even before seeing Ukrainian Diary at The Photographers’ Gallery, I found myself thinking about its title. The idea of a diary fits naturally with Mikhailov’s work: instead of creating a grand, official narrative inherent to Soviet photography, he developed an intimate and fragmented way of seeing. The term Ukrainian, however, is less straightforward. Some of his more recent bodies of work that directly address Ukrainian events: Parliament (2015–17); and Temptation of Death (2014–19), which adopts the Kyiv Crematorium as its binding motif, are not included in the exhibition.

Mikhailov began challenging Soviet photographic norms as early as the mid-1960s, working with a circle of like-minded friends. At the time, photographing “for no reason” could be equated with spying; showing Soviet life as anything less than ideal was seen as an attack on communist values; and photographing the naked body could result in prison. Mikhailov did all of this and more. He turned his camera toward mundane subjects, mixed genres freely and questioned photography’s claim to present an ultimate truth. By subverting idealised Soviet imagery, he proposed a raw, ironic, and unremarkable version of reality, always seeking to capture the spirit of his times through the everyday. Or, better yet, to condense that spirit for others, not through words but through a visual semantics of his own making.

Art historian Nadiia Bernard-Kovalchuk reflects on whether Ukrainian is an appropriate label for the Kharkiv School of Photography, of which Mikhailov is a founding figure. She writes that “the school’s activities stretch between two heterogeneous historical realities: on the one hand, Brezhnev’s ‘stagnation’ and the perestroika fatal to the USSR, and on the other, the economically brutal birth of the Ukrainian state.” [2] This dramatic time span, during which Ukrainians experienced long-awaited yet destabilising transformation, offers a more fitting temporality for understanding Mikhailov’s work in Ukrainian Diary. Geographically, most of his projects take place in what was first Soviet Ukraine and later became independent Ukraine. Temporally, however, they exist within a landscape marked by ruptures, discontinuities, and perpetual new beginnings.

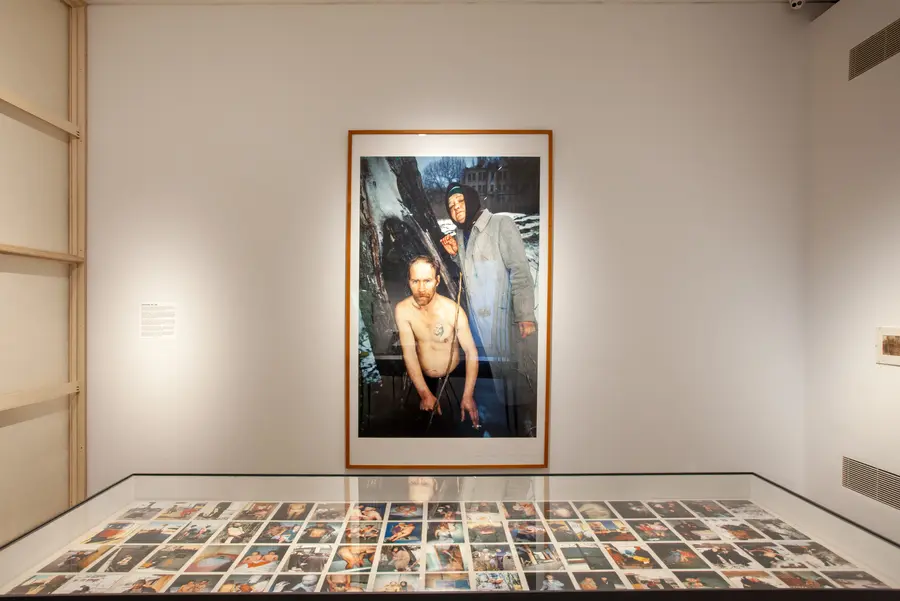

In the preface to one of his most audacious works, Case History (1997–98), Mikhailov reflects on the lack of a photographic record documenting complex historical shifts in Ukraine: “I was aware that I was not allowed to let it happen once again that some periods of life would be erased.” [3] After returning to Kharkiv from a year in Berlin, he was struck by the stark divide between the newly rich and the newly poor, a process already in full swing. Yet his aim in photographing the homeless did not follow the classic documentary model, such as the USA Farm Security Administration’s work, which sought to highlight a social problem and prompt state intervention. Instead, by showing the everyday lives of those most affected by the collapse, Mikhailov “directly assaults the onlookers’ sensitivity” [4] and “transgresses the acceptable limits of representation,” [5] His goal was not to provoke pity or shock though.

Rather, Mikhailov asserts something more fundamental: the individual’s right to exist and express themselves beyond convention. Through his unwavering attention to ordinary lives, he bears witness to massive transformations unfolding beyond any single person’s control. Ukrainian Diary, then, is not simply a national label or a chronological record. It is a testament to how one artist has persistently documented a world defined by instability, reinvention, and the fragile, but enduring presence, of everyday life.

Get to know Kateryna Filyuk

Kateryna Filyuk is a curator and researcher, who holds PhD from the University of Palermo. In 2017-2021 she served as a chief curator at Izolyatsia., a Platform for cultural initiatives in Kyiv. Before joining Izolyatsia, she was co-curator of the Festival of Young Ukrainian Artists at Mystetskyi Arsenal, Kyiv (2017). The co-founder of the publishing house 89books in Palermo, she has participated in curatorial programmes at Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo (Turin, 2017), De Appel (Amsterdam, 2015–16), the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (Seoul, 2014) and the Gwangju Biennale (2012). In 2023 Filyuk was a visiting PhD student at the Central European University (Vienna) and in 2024 a visiting researcher at FOTOHOF Archiv (Salzburg) and the Predoctoral Fellow at the Bibliotheca Hertziana (Rome). Currently she develops a two-year scholarly initiative – the Methodology Seminars for Art History in Ukraine in collaboration with the Bibliotheca Hertziana and the Max Weber Foundation’s Research Centre Ukraine.

Footnotes

- Boris Mikhailov, “Everyone has became more circumspect…,” in Tea Coffee Cappuccino (Köln: König, 2011), 230.

- Nadiia Bernard-Kovalchuk, The Kharkiv School of Photography: Game Against Apparatus. Kharkiv: Museum of Kharkiv School of Photography, 2020, 17.

- Boris Mikhailov, Case History (Zurich: Scalo, 1999), 7.

- “Symbolic Bodies, Real Pain: Post-Soviet History, Boris Mikhailov and the Impasse of Documentary Photography,” in The Image and the Witness: Trauma, Memory and Visual Culture (London: Wallflower Press, 2007), 58.

- Olena Chervonik, “Urban Opera of Boris Mikhailov,” MOKSOP, accessed November 25, 2025, https://moksop.org/en/urban-opera-of-boris-mikhailov/