To respect the camera’s “candid, detached vision”, and to develop “a photographic imagination – the ability to visualise the world in "photographic terms”

The young man, tall, serious looking in his black polo neck jumper, hair parted and swept neither fashionably nor unfashionably to the right, turned the corner into a West London Street. It was 1956 and in his 27th year and despite living not far away, he had never come this far out of his neighbourhood before. As he crossed the line between the ‘good areas’ and the ‘slums’ – which is how his mother, in horrified tones, referred to streets like these – he was hit first by the noise and then the sight of children. They were everywhere, it seemed: laughing, howling, screaming, crying, kicking balls and playing games. Women sat gossiping on doorsteps, smoking, playing cards whilst the men lounged languidly, joking with each other or trying to catch the attention of some passing girl. This was a world apart from Cambridge where he was born – where the streets were silent and family interaction, such as his was, took place indoors – and he loved it. Here, life exploded chaotically but beautifully onto the pavement; and on that Saturday morning, with all its disorder and decline, it looked to him a near perfect evocation of how life should be.

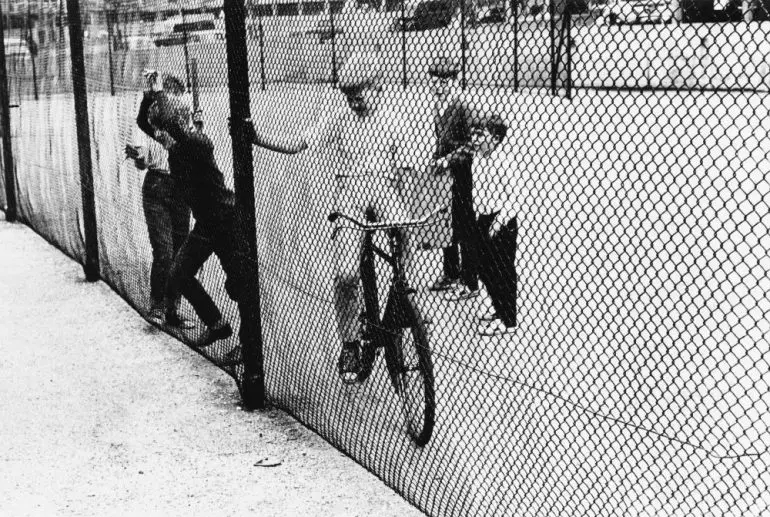

His first thought was to capture it on film – for the bulldozers had already ploughed through similar locales to make room for the modern council estates that he found so cold, structured and formal. He didn’t belong on these streets but nobody seemed to mind him being there and he’d long ago learnt the art of being present yet invisible. Falling into the street’s shadows, he took out his camera.

Roger Mayne took 64 photographs that first day on Southam Street and returned frequently, shooting around 1,400 negatives between 1956 and 1961 before it was demolished to make way for Erno Goldfinger’s Trellick Tower. Many of this first batch were exhibited (alongside his pictures of Teds and street gangs) in Photographs from London, his first London solo show, at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in June 1956.

Self-taught, Mayne took up photography while studying chemistry at Oxford University in the late 1940s. His student days saw him open up artistically, assimilating the photography of Walker Evans, Paul Strand and absorbing the work of Matisse and watching ‘serious’ films by such figures as Akira Kurosawa. Later, in 1952, he would acquire Henri Cartier-Bresson’s new and hugely influential book The Decisive Moment, which ignited the humanist direction of his work.

It was also during this time that he met Hugo van Wadenoyan, one of the most enduring influences on his work. Almost forgotten today, Dutch-born van Wadenoyan was a professional studio photographer and author of practical ‘how to’ photography books. In 1951, Mayne had made his debut in Picture Post with a photo essay in colour on the making of a ballet film. Wadenoyan encouraged him, recognising his talent and providing Mayne with perhaps the single most important and liberating lesson of his career: to respect the camera’s “candid, detached vision”, and to develop “a photographic imagination – the ability to visualise the world in "photographic terms”.

—Anna Douglas

This essay can be read in full in Volume 3.1 of Loose Associations, The Photographers’ Gallery’s printed journal on photography and image culture, available here.

Anna Douglas is an independent curator and researcher drawn to post-war culture. She was curator of the Roger Mayne exhibition at The Photographers’ Gallery, March – June 2017, and previously curated the touring exhibition, Shirley Baker: Women and Children; and Loitering Men, shown at TPG in 2015.