On the night of 29 January 1963, Tony Mella staggered from the dimly lit Bus Stop strip club he owned in Dean Street with three gunshot wounds, to bleed kerbside into one of his hostess’s laps. Mella was a hard man, said to be responsible for keeping the Kray Twins out of Soho, but this night changed that. He had been shot by his minder, Alfred Melvin. After discharging his handgun three times into his boss, Melvin blew out his own brains with one careful shot under the chin. As Mella lay bleeding, photographers from the Daily Herald were quickly dispatched. The resulting bleak, direct-flash picture shows the police, their Triumph motorcycles parked up, having arrived expecting a routine gangland shooting only to be faced with a personal attack. The photograph looks strangely Weegee-esque, suggesting a New York crime scene rather than London Town. Clip joints like Bus Stop promised punters no-holds- barred stripteases and strong beer, but in reality both the beer and the performances were watered down. These were wallet-stripping rackets with no recourse to complaint. Soho, a square mile in the heart of the city, stained by police corruption, had become a law unto itself. A 1957 picture-led feature in VUE magazine described it as ‘the world’s wickedest mile’ and ‘like a cancerous sore’ [2] while contemporary sociologist Dick Hebdige recognised the area’s unfettering qualities: ‘Soho became the perfect soil on which thriller fiction fantasies and subterranean intrigue could thrive.' [3]

Emerging from the greyness of 1950s post-war rationing, Soho lay behind the sweeping classical curve of John Nash’s Regent Street, designed to create a kind of architectural modesty panel between posh Mayfair and a debauched hinterland. A Historic England archive photograph of Regent Street in the 1860s – sun awnings extended, horse-drawn traffic flowing – shows the curve fulfilling its function admirably. The cocaine-fuelled clubs of the 1920s like The 43 on Gerrard Street had been lively enough, but by the 1960s Soho was outperforming even its own reputation for sleaze, overrun with ‘fixed’ roulette wheels, one-armed bandits, adverts for ‘French lessons’, three-card trick teams and bent coppers. Sensibly, the UK’s first all-night store, Boots the chemist, was conveniently positioned on Piccadilly Circus – visitors could pick up French letters before venturing into the area. All components of the market economy – speculation, concealment, exploitation – existed in Soho in microcosmic form. Soho’s emergence as the international epicentre of youth fashion, pop, rock and punk was still to come.

Today’s Soho – with its juice bars, galleries, retro stores, chain shops and thriving LGBTQ+ community, and now bracing for the footfall explosion that will result from Crossrail’s new stations – seems a world away from that fateful 1963 night. Its porn shops have faded, now numbering just a dozen or so, with those that have survived seeming like quaint heritage features. Institutions like the Gay Hussar (haunt of Leftist politicians), Madame Jojo’s, the Valbonne (a Jagger and Hendrix hangout with decadent heart-shaped pool, chronicled by Fleet Street’s first female staffer, Doreen Spooner) and Hopkins, Purvis & Sons (purveyors of artists’ pigments and dating back almost to when Canaletto attempted to sell his paintings from his Soho home) [4] – all these monumental slabs of Soho history are gone, and a total collapse of community is now feared. There are survivors, such as the immutable pocket-sized Bar Italia, Ronnie Scott’s jazz venue (captured in Val Wilmer’s moody 1969 image of drummer Andrew Cyrille), the Groucho Club (whose golden era in the 1990s drew David Bowie and George Michael) and I Camisa & Son delicatessen (est. 1929) on Old Compton Street, the mingling smell of Parmigiano and Milanese still inciting passers-by.

The area retains a high level of historical colour and entrenched political resistance. Soho was, after all, where Karl Marx thought through Das Kapital. It was also the birthplace of groundbreaking feminist magazine Spare Rib (driving issues of the day such as domestic violence), the home of Private Eye (perfecting speech-bubble satire) and the site of the invention that took the world by storm: television, with its first public transmission from the garret of what is now Bar Italia. In the 1960s and 1970s, offbeat characters like Soho stalwart Jeffrey Bernard – infatuated by the anarchy of the place and its watering holes – could be seen with Francis Bacon, Dylan Thomas and Marlene Dietrich. It is no surprise, then, that Soho has been crisscrossed by so many great photographers, including Margaret Bourke-White, Ernst Haas, Ida Kar, Kurt Hutton, Jill Freedman, Henry Dixon, Robert Doisneau, Henri Cartier-Bresson and even Beaumont Newhall, the father of what turned out to be a quite flawed history of photography. This truncated list is astonishing for just one square mile and allows Soho to be analysed from contrasting temporal perspectives.

Stephen Fry, who co-founded the Save Soho campaign in 2014, commented in a BBC radio interview: ‘‘It’s the most creative square mile on the surface of the planet [...] such a magical place – there’s nowhere else like it.’[5] From the beginning, Soho had been a Georgian experiment in racial liberalism, with the area being transformed from green hunting land into a commercial powerhouse mostly by French Huguenots, first- rate artisans and speculators despite their sober outlook. ‘Invention’ became part of Soho’s DNA, mysteriously passed down through centuries. Soho became famous for piano makers, camera manufacturers, diamond cutters and, later, home to recording studios, advertising agencies and the film industry (Soho stories providing a scriptwriter’s heaven).

Photographs, such as those from Historic England, make evident the loss of industry that has taken place. These include a 1905 image of Wardour Street’s Mitchell Motor Works car park, which ferried theatregoers’ cars over five storeys via a system of lifts and turntables, through to the majestic Salle Erard concert hall on Great Marlborough Street, a bronze medallion head of Mozart visible on the front elevation (the child composer having lived and performed in Soho in 1764–65). A print showing this long-gone building is preserved in City of Westminster Archives, and the materiality of this photograph when held in the hand adds to the sense of loss. Just around the corner in Argyll Street, Edith Garrud trained suffragettes in jujitsu martial arts,[6] the photographs providing a fascinating glimpse into the women’s preparedness for physical confrontation with the police.

The Second World War temporarily put a damper on Soho. Photographs of the Blitz – bomb damage on Ramillies Street (home to The Photographers’ Gallery); St Anne’s Church missing its nave; a spectacular crater on Charing Cross Road; gas mask training on Shaftesbury Avenue – show how destructive the air raids were. The Windmill Theatre, famous for French-inspired burlesque, prided itself on never closing its doors. Bill Brandt was there on assignment in 1942, to prove it to readers of Lilliput magazine. While not averse to staging a deceptive moment, Brandt produced brilliant wartime pictures of Soho that demonstrated the area’s resistance. His caption for an image showing Windmill dancers peeping out at the servicemen in the audience reads, ‘They are as nervous as troops going over the top’.[7] His 1942 picture of a waiter delivering a silver-service lunch amid bombed streets exemplifies Soho’s resilience. A Hulton Archive image of the Windmill dancers in 1940, their outfits completed by gas masks and hard-hats, stands testament to the difficulties of the decade.

By the late 1940s recovery was signalled by new arrivals like Dean Street’s Colony Room Club (opened by Muriel Belcher, with Francis Bacon as a founding member). A sign behind the bar that read ‘Violence and Sensation’ seemed to sum up Soho well. Forty years later, photographer Clancy Gebler Davies would be given full access to the club when working to pay off her extensive bar bill, leading to candid photography of the shenanigans of Brit artists like Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst and Gavin Turk.

Benefiting from the post-war boom, it was business as usual by the 1950s and the internationalisation of Soho was in full flow. Jazz and Jamaican vibes rose from basement clubs; photographs like Sergio Larraín’s 1958 image of a Soho pub perhaps conceal the complexities of racial tensions. The annual Soho Fair with its traditional waiters’ race was joyful – even ‘art’ photographer Jean Straker, who later brushed with the Obscene Publications Act, had a float in 1956. Writer Frank Jackson commented in 1959: ‘It’s unlikely that anywhere else can you buy, in addition to all the usual things, meat from a Pakistan butcher, killed Muslim style, or such Far East delicacies as Salt Fish Pickles, Gulab- Jamun and Rosogolla and Formosa Jasmine Tea.’8 Willy Ronis’s dreamy 1955 shot of the French House pub on Dean Street shows a lazy sun-drenched afternoon, inviting contemplation of what creates tangible atmosphere in a photograph. And, following in the footsteps of the original Chinatown in London’s Limehouse, Soho developed its own around Gerrard Street, new restaurants cashing in on returning servicemen’s cultivated taste for East Asian food, fusing business growth with the needs of the local Chinese community.

By 1966, Soho’s time in the international limelight had arrived. Carnaby Street became minted. The force of Mary Quant, Twiggy, Justin de Villeneuve and Leonard of Mayfair drove a new fashion-led counter-culture, culminating in punks and New Romantics. Carnaby Street, however, soon became a victim of its own success, a jingoistic tour-bus destination. Burt Glinn’s 1969 photograph of a shopper in a flower-power minidress gazing into Carnaby’s first women’s boutique, Lady Jane, relives the best times, along with a memorable shot of the trend-setting John Stephen, ‘King of Carnaby Street’, outside his shop.

Soho was also developing serious pop and rock credentials. Photographs from inside Trident Studios on St Anne’s Court show their sought-after Bechstein grand piano, cradle of 1970s hits including ‘Life on Mars’, ‘You’re So Vain’, ‘Hey Jude’, ‘Without You’, ‘Walk on the Wild Side’ and ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’, the piano much fancied for its brittle timbre. In 1969 Ray Stevenson captured Trident’s laid-back vibe with a picture of David Bowie, John ‘Hutch’ Hutchinson and Hermione Farthingale (recording as Feathers) unwinding with guru Tony Visconti, an Evening Standard planted on Hutchinson’s lap with the headline ‘“Go Easy on Pot Smokers” Jim is Told’. We are fortunate to have documents showing The Beatles (wearing kaftans), The Yardbirds, Joan Armatrading, Marianne Faithfull, Jimi Hendrix, Led Zeppelin, Sex Pistols and The Jam, as well as earlier artists like Tommy Steele and The Vipers Skiffle Group (all finding their feet at the 2i’s Coffee Bar), Georgie Fame (an auspicious portrait at just sixteen by Roger Mayne), Sammy Davis Jr and Frank Sinatra, all of whom could be seen performing in Soho.

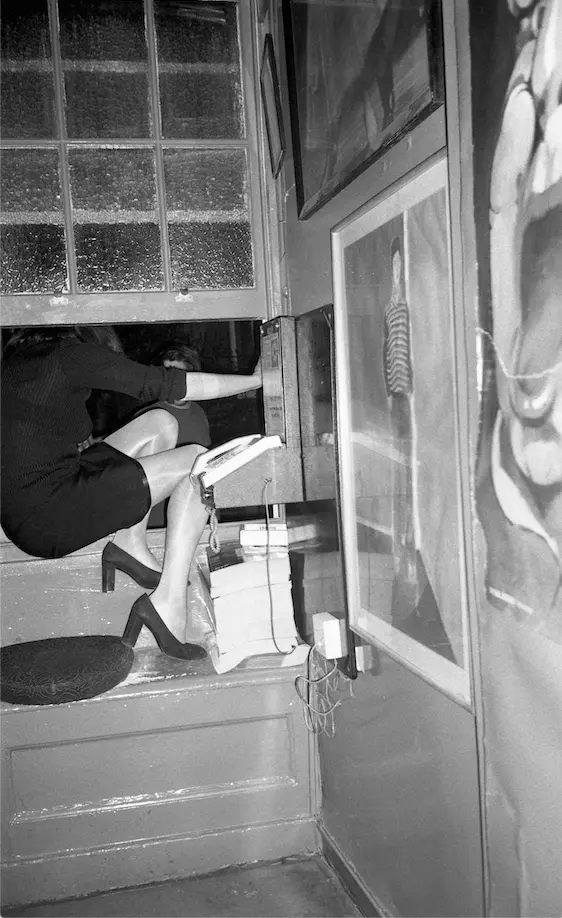

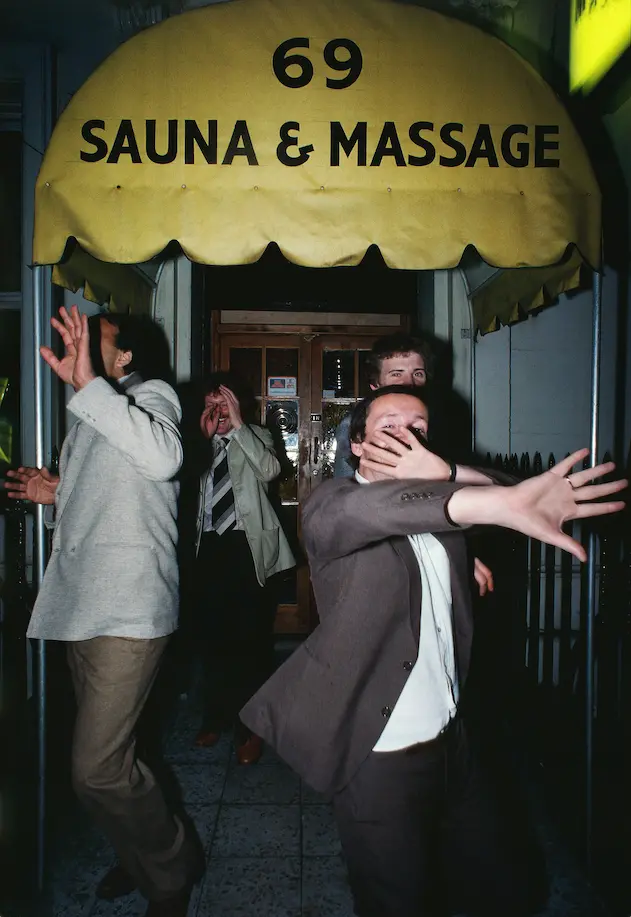

In the 1960s and 1970s, news photographers had to be hardened to operate at Soho’s criminal edge. Sunday Times staffer Kelvin Brodie’s physicality and hard-as-nails look made him a perfect fit. Describing his Times photographers, editor Harold Evans said: ‘[They] struck me rather like Battle of Britain pilots, lounging around with their cameras around their neck ready to take off on hazardous missions at a moment’s notice.’[9] East Ender Brodie was in great company: Bryan Wharton, Sally Soames, Philip Jones Griffiths and Don McCullin had all put their lives on the line in global conflicts. Brodie was persistent, working up close to his subjects without impacting circumstances and making the most of low light despite the limitations of film. His Soho work from the late 1960s – as he worked alongside West End Central police, sweeping for drifters and extricating young teenagers from Soho’s dirtier clubs – really gets under the skin. His work also went into the trailblazing Sunday Times Magazine, which was working to proprietor Roy Thomson’s principle that ‘there was money to be made in Britain with colour’.[10] Evans recalls, ‘We weren’t aware of it at the time but the magazine was itself a tiny chip in the mosaic of the swinging 1960s.’[11] Investigative and unflinching, the magazine’s photo spreads and grids (shaped by art director Michael Rand) still look fresh today. Pictures, often shocking, jumped off the page straight onto Sunday breakfast plates. In addition to the staffers, international giants including Eve Arnold, Bruce Davidson, Eugene Richards, Brian Duffy, Lord Snowdon, David Bailey, Terence Donovan, Diane Arbus and William Klein were commissioned, all attracted by the magazine’s reputation. Soho fortuitously got the irreverent Klein in 1980; it was a match made in heaven. Back in 1956 Klein had shaken up street photography forever with his book New York, a series of ‘prototypes’ for how photography could bend reality rather than reflect it. In Soho he managed to strip back the square mile to bare essentials – the last gunmakers, strip clubs, punks, the local Rotondos family, the Raymond Revuebar and, of course, Francis Bacon – the feature abetted by Denis Herbstein’s clever words.

A few months prior to Klein’s shoot, on a muggy August night, the mass murder of 37 people occurred in Denmark Street, a disaffected customer having taken petrol and rag to the club El Hueco (also known as the Spanish Rooms and popular with Latin Americans), [12] in the same street that saw the first Rolling Stones album recorded and which was home to La Giaconda, a café frequented by The Kinks, Bowie and Elton John. So rapidly did the fire spread that distressed Soho firemen attending the scene said, ‘People seem to have died on the spot . . . with drinks still in their hands.’[13] It is perturbing that there is still so little awareness of this attack that took the lives of many immigrant workers.

There are many striking photographs that have given form to the ever-changing moods and iconic figures that define Soho, ranging from Christine Keeler astride that chair (hers was the perfect Soho story, involving model, government minister and Soviet attaché) to an awkward Johnny Rotten on Carnaby Street. Captured moments of lust, celebration and hedonism are quickly overturned by outbursts of violence and desperation, as is the case in what might be two of Soho’s most affecting images: Neil Libbert’s photograph of the racist and homophobic nail bombing of the Admiral Duncan pub in April 1999 – surely a direct attack on the inclusivity that is synonymous with the area – and the monochrome image of boxer-turned-celebrity Freddie Mills sitting lifeless in the backseat of his Citroën DS in Goslett Yard.[14] As a collection, Soho photographs offer a heady mix of scrutiny and nostalgia. They show the street as stage and go a long way to identifying Soho’s neoteric disposition: a place in which instinct and interaction are at their most heightened.

– by Julian Rodriguez

Footnotes

2 ‘World’s Wickedest Mile’, VUE: America’s Photo Digest 10:1 (January 1957), n.p.

3 Dick Hebdige, Style of the Mods (Birmingham: Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, 1974), p. 6.

4 Roy Castle, ‘A Slice of Soho’, Sunday Times Magazine, 21 January 1968, pp. 24–25.

5 ‘Stephen Fry Stands up for Soho’, ITV News, www.itv.com/news/london, 13 January 2015.

6 Tony Wolf, Edith Garrud: The Suffragette Who Knew Jujutsu, ed. Kathrynne Wolf (Lulu.com, 2009), p. 67.

7 Bill Brandt, ‘Back Stage at the Windmill: Ten Minutes to the Show’, Lilliput 11:4 (October 1942), p. 329.

8 Jackson was writing in the 1950s and his choice of words is reflective of the era. Frank Jackson, ‘Shopping in Soho’, What’s On in London, Soho Fair supplement, 11 July 1958, pp. xiv–xv.

9 Harold Evans in conversation with the author, 8 January 2019.

10 Denis Hamilton, Editor in Chief: Fleet Street Memoirs (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1989), p. 104.

11 Harold Evans, My Paper Chase: True Stories of Vanished Times (London: Little, Brown, 2009), p. 344.

12 John Withington, London’s Disasters (Stroud: The History Press, 2010), p. 96.

13 Ibid., p. 98.

14 James Morton, Fighters: The Lives and Sad Deaths of Freddie Mills and Randolph Turpin (London: Time Warner, 2005), pp. 298–304.