Geraldo de Barros concentrated on photography within two periods of time, each resulting in a significant body of work.

The Fotoformas, produced between 1949 and 1951, inaugurated his reception within a modernist critical milieu. The Sobras (Remains) were produced comparatively recently, over the last two years of his life between 1996 and 1998.

The two series are each connected in different ways to significant public moments. At the Museu de Art Sao Paulo the exhibition ‘Fotoforma’ (1950-1951) was an opportunity for de Barros to consolidate the process of photographic experimentation he began in 1946 – and the series gained that title through this process. ‘Fotoforma’ also marked the provocative and decisive intrusion of the medium into critical debates previously centred on painting and sculpture. As such it also contributed to a change in the reception of photography in Brazil – which was cemented by the inclusion of a selection of work by members of the Foto Club Cine Bandeirante at the II Sao Paulo Biennale in 1953.

The Fotoformas were shown again as a complete series four decades later (but for the first time in Europe) at the Musee D’Elysee, Lausanne in 1993. The reception of this body of work coincided with a process of return that de Barros had commenced gradually since 1988, when he started to work through boxes of prints and negatives first unearthed from storage, by his daughter, in 1975. The Musee D’Elysee exhibition was followed by a retrospective in Sao Paulo, a year later. After the impetus of a public re-embrace of his photographic work, de Barros tentative photographic re-workings picked up pace and certainty, resulting in the production of the Sobras.

Sobras is a series of work that de Barros began at the end of his life, but it is also one provoked by a need to recall his first motivations for engaging with photography. It was formed by a process of looking back that acted against both both nostalgia and narrative, inviting the intrusion of the present. What Remains, the first retrospective of Geraldo de Barros’s work in the UK, takes this moment as its starting point. It hopes to convey the attitude of an artist who, fortunate enough to be witness to the beginnings of his own historicisation, chose to submit his photographic practice to a further degree of chronological disobedience.

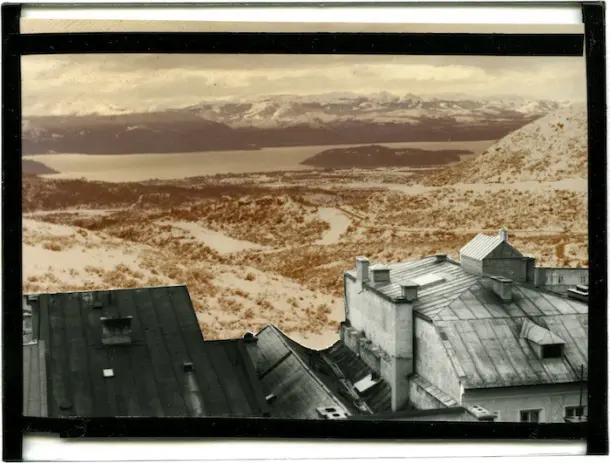

Sobras includes series produced by using three different techniques. The most numerous are images produced from negatives cut-into and remounted on glass plates. The negatives began life as snapshots, the informal documentation of a life-time of holidays and road-trips. On the surface of fresh, altered prints, shapes subtracted from each negative intrude forcefully, disrupting an (apparently) casual gaze. The composition that more intuitively directed the framing of original images is re-emphasised by cut-out spaces and drawn lines. Spaces, abstracted and impenetrably black, meet the photo-real images that they outline and isolate; reflective surfaces are reversed.

The set of Sobras subtitled Vidros (Glasses) emerges from the process used to compose images on glass but begins from the faded image rather than its negative and results in a series of photo-objects. Slices and glints of light (or rather, shapes made by windows, opened doors, sun on water) are excised to form openings within the surfaces of the paper. The foreground of one snapshot is made to co-exist with the background of another, an anachronism that is emphasised where monotone meets colour. The final group, photo-collages on paper, creates the most explicit connection from the Sobras back to the Fotoformas. The source material for works amongst this series are reproductions of his earliest images – produced for a book published when the Fotoformas were shown in Sao Paulo in 1994. Amongst these, two stand out by performing a significant reversal – recomposing the most abstractly iconic of the Fotoformas into sail boat collages. Images that have been frequently interpreted as the search for linear geometry are released, freely following a chain of figurative associations.

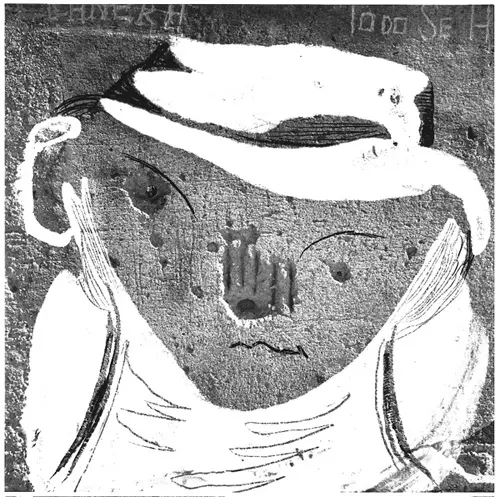

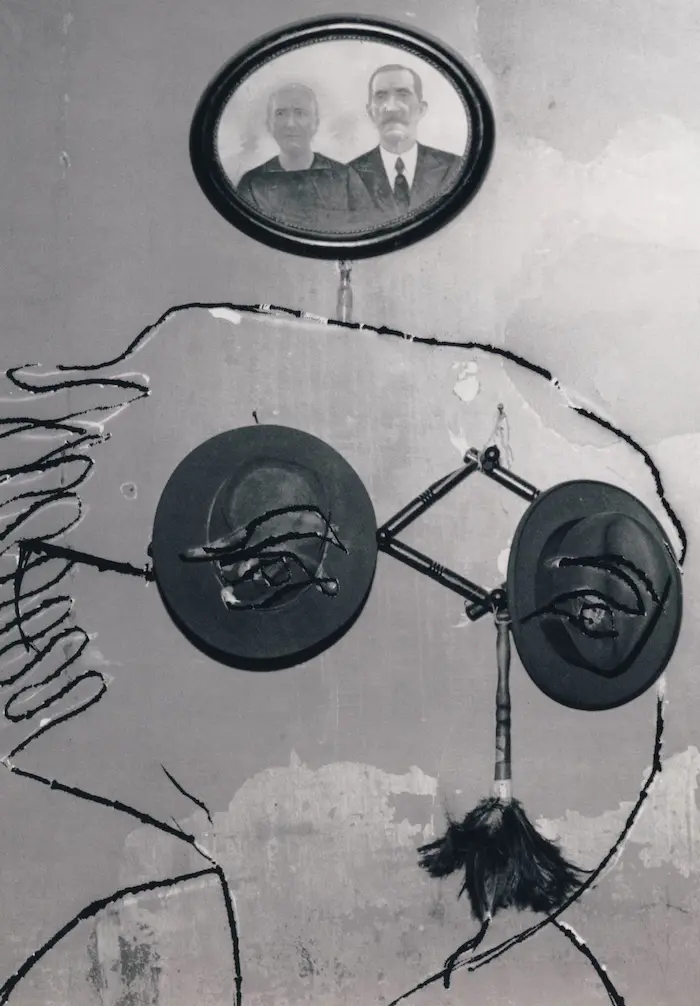

The process of cutting into the negative surface was an echo of one used widely within the Fotoformas. In works such as Untitled, Fotoforma, 1949 circular sections of the negative were freed from orientation by cutting, turning and re-placing. In numerous others, the cut is a crop. De Barros produced many of his most celebrated (apparently ‘straight’) photographs after re-framing, re-composing and therefore improving upon the original moment of their capture. This decisive cut was rehearsed, by outlining his intentions in pen on contact prints. To produce certain Fotoformas de Barros drew directly on to the surface of the negative. The figure (a bird, a cat, a portrait) suggested by found configurations was transformed into a permanent record and the reproductive process flattened drawn and photographic line into representational equivalence.

De Barros therefore confined neither his skills nor his or aesthetic judgements to the precise moment of photographic capture. And neither did he privilege the reality imprinted by that time. The decisive moment was not sacrosanct and he was concerned with technique only to the extent that it was ‘necessary’. What he did choose to master, however, was chance. He invited error. This attraction to risk demanded a greater degree of dexterity than the ‘cults of technical perfection’ that also emerged within fields of photographic experimentation at the time of the Fotoformas.The results of de Barros decidedly non-anxious mastery of chance are particularly evident in images composed semi-blind. Using multiple exposure he superimposed changing fragments of the ironwork roof spaces of Sao Paulo’s iconic Luz station, as well as the particular shapes formed by light intruding through an open door (the latter resulting in images that confound any immediate understanding of either technique or referent).

Fotoformas contain variations not only in terms of photographic technique. As a set of images they move fluidly across a range of approaches to realism (all of which were being competitively contested, within art criticism as well as the circuit of amateur Fotoclubs that lent de Barros his formative context as photographer). At one end of this scale are images that are often loosely aligned with the orthodox Concretist paintings that de Barros produced as a member of the Ruptura movement (1952-59). Occupying a contradictory position are the expressionistic, free-form images formed by drawing on to negatives. Between the two are those that extract form and geometry from the intersections and shadowed layers of recognisable day-to-day objects (windows, doors, vessels, pylon lines, balloons, people). Another set depicts found writings and images (dice, balloons, boats) anonymously scratched into walls.

For their first exhibition at MASP, de Barros’ contradictory representational arguments were explicitly brought into relationship with one another. He selected the works himself and employed display devices that re-invented and radically altered them (yet again). A group of four images, for example, was collected within a frame suspended from the ceiling. The selected photos alternate in representational style and further complication is added by the intrusion of both opaque painted squares and openings – which capture fragments of exhibition space. An actual background behind the ground of the images themselves and their frame was drawn into the overall composition. An image of a window seems to extend into the actual window of space behind it. Individual images were also mounted at the corners of painted boards or fixed onto the vertical metal tubes normally used as display board supports. A group of Fotoformas produced by cutting photographic prints – according to outlines lent by both drawn or photographed forms – were displayed on plinths as if sculpture. This heterodox method of display and juxtaposition created contiguities between modes of realism – from those contained by the photographs themselves towards a perception of the situation within which they were being viewed and the indeterminate reality of the photograph itself, which was presented as both image and object.

De Barros‘ approach to display suggests that the series was deliberate in its internal contradictions. This is not, however, a characteristic of the Fotoformas often emphasised by art historical narratives, many of which have been oriented by relation to his subsequent turn – from photography to abstract painting. De Barros was involved in the formation of the Concretist group Ruptura shortly after returning from a year in Europe (1951-1952). In Paris he had enrolled in the École National Superiéure de Beaux Arts and studied print-making with Stanley Hayter. From there he had travelled to Spain, Scotland, Germany and Italy – and to Zurich to meet Max Bill.

Bill was a key influence on the development of Concretist art in Sao Paulo and an artist whose work de Barros had seen for the first time at MASP shortly before his departure. The Ruptura manifesto, authored by Waldemar Cordeiro and signed by all members including de Barros, outlined a rigorous approach to abstraction. It defined Concretism as resolutely objective and deliberately anti-representional. With no trace of either gesture or referent, it was to be restricted to primary colours and compositions that prevented the picture plane being perceived as figure and ground. The manifesto asserted a search for the new, which would be achieved through a break with the old, namely “all the varieties and hybridizations of naturalism’ including the “mere negation of naturalism i.e. the “incorrect” naturalism of children, mad people, “primitives”, expressionists, Surrealists etc”.

De Barros’ meeting with Bill, followed by his turn towards painted abstraction, lays a tempting narrative into place, one that views the Fotoformas as a ‘proto-abstract’ journey towards the Concretist conclusion and thus privileges the more overtly geometrical images within the series. De Barros post-Ruptura trajectory however, does not invite a reductive interpretation of his photographic practice. He remained a member of the group until it 1959 dissolution but it was not the sole centre of his activities and later turns were yet to come. That is not to say that his prolonged exploration of Concretism was forgotten, it acutely heightened his understanding of form and composition, which informed his graphic and furniture design (as well as the Sobras), and re-emerged definitively at later moments. His formative interest in abstraction does occur within the production of the Fotoformas – but the series as a whole cannot be defined by this. The Sobras, as a deliberate return to photography, again marked out the distinct parameters of his approach to this particular medium.

De Barros did not adhere to the specificity of photography in terms of its being a privileged imprint of time truth or memory. He viewed it as ‘print-making’ and invited different means of capturing experience, such as drawing, into its documentary surface. Photography however is specifically pursuasive as a representational form. It locates itself – undeniably- within day-to-day experience. This medium in particular lent a certain emphasis and orientation that allowed de Barros to interrogate relationships between other varying forms of capturing experience, to overlay document with the making visible of imaginative or formal associations – and to collapse different moments of time into a single image (one that could also be cut into and apprehended as a material object in space). This interrogation of representation was marked out by both the Fotoforma exhibition and even before this – by the first set of images he composed with his 1939 Rolleiflex – produced when he set out to photograph the same scenes and situations that previously he had painted. As a final testiment of engagement with photographic practice in particular the Sobras deploy the same willful heterogeneity.

— Isobel Whitelegg

Dr Isobel Whitelegg is an art historian, lecturer, curator, and Programme Co-Director, MA Art Museum and Gallery Studies, University of Leicester