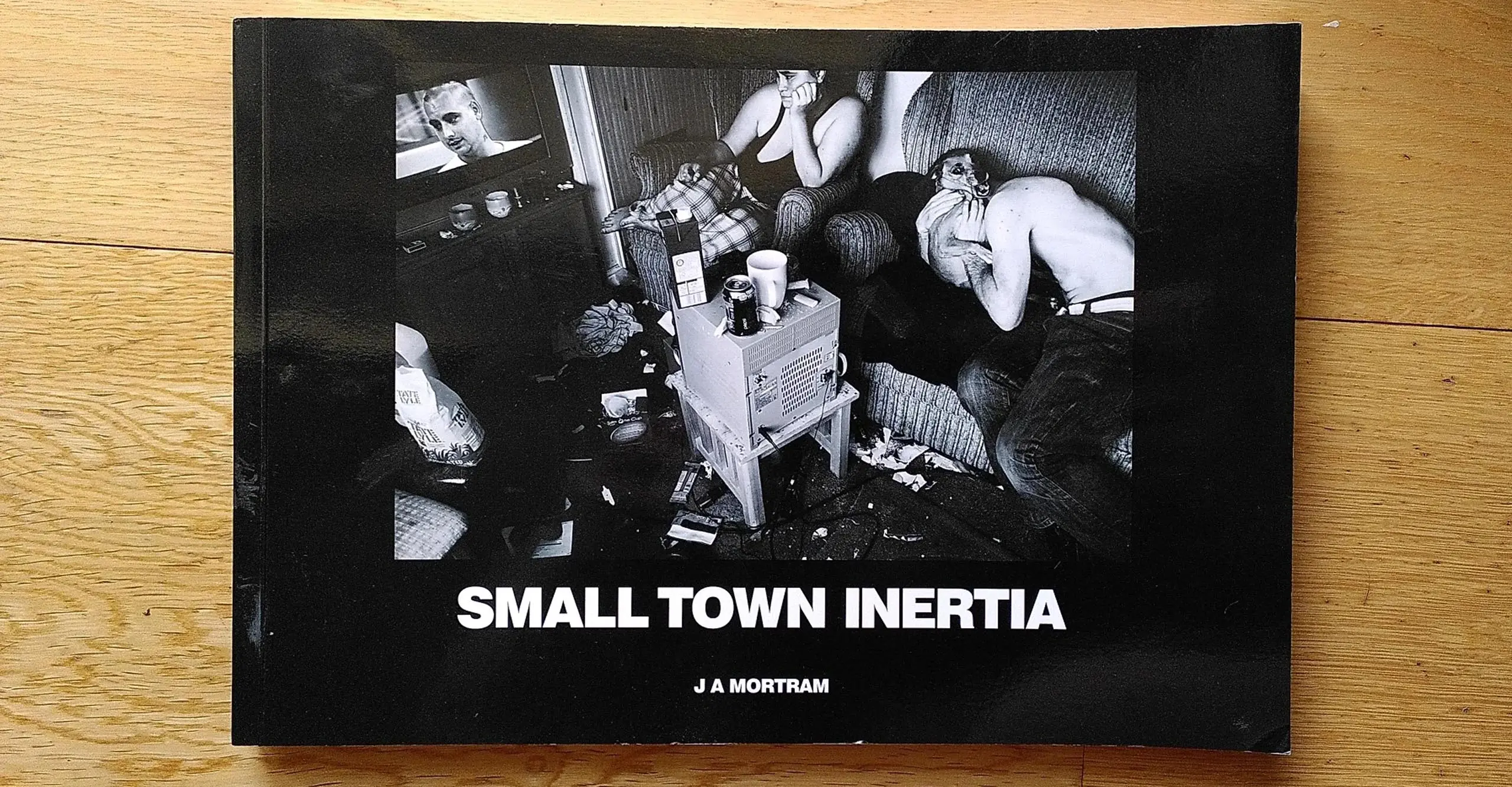

Josephine Ellis reviews the photo book Small Town Inertia by Jim Mortram.

Jim Mortram’s Small Town Inertia is an intimate exploration of the people living in his hometown of Dereham in Norfolk, England. As one of Norfolk’s most deprived towns, Dereham serves as a microcosm reflecting a broader narrative of British communities struggling in the face of welfare and health care cuts. Mortram’s subjects consist of people united in their shared experiences of poverty and social exclusion, yet simultaneously isolated in navigating their personal pasts and present challenges. Mortram immortalises these people’s lives in the act of commemoration - their faces and voices suspended in time as a form of oral history, testifying to political failures.

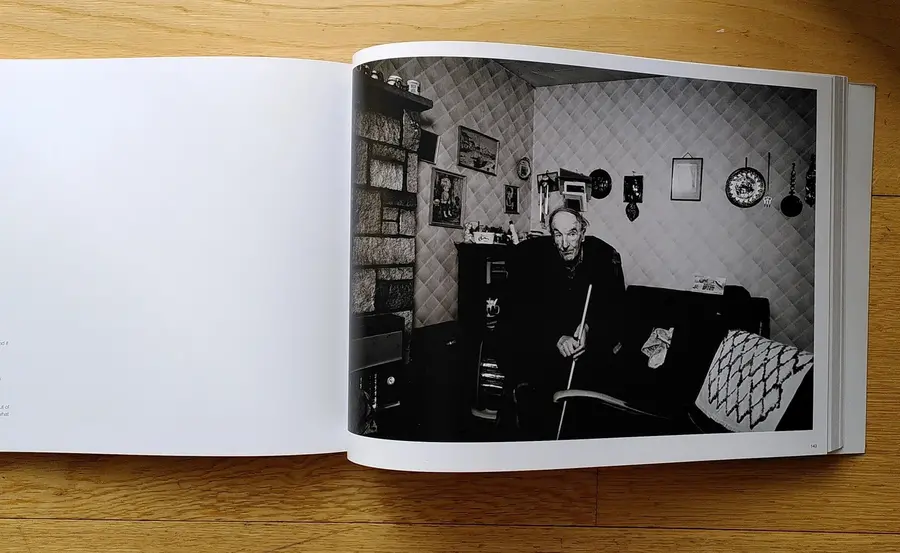

Small Town Inertia introduces us to a collection of people who repeatedly appear throughout the book, their histories and lives unravel, intertwined in a finely spun web of photo documentation. Mortram’s reportage, photo-documentary style allows for a sensitive navigation of people’s deeply personal stories, pervaded with struggles resulting from disabilities and abuse. We are introduced to David, with whom Mortram has developed a particularly close friendship. David is blind, and the death of his mother, Eugene, exacerbates his feelings of intense loneliness.

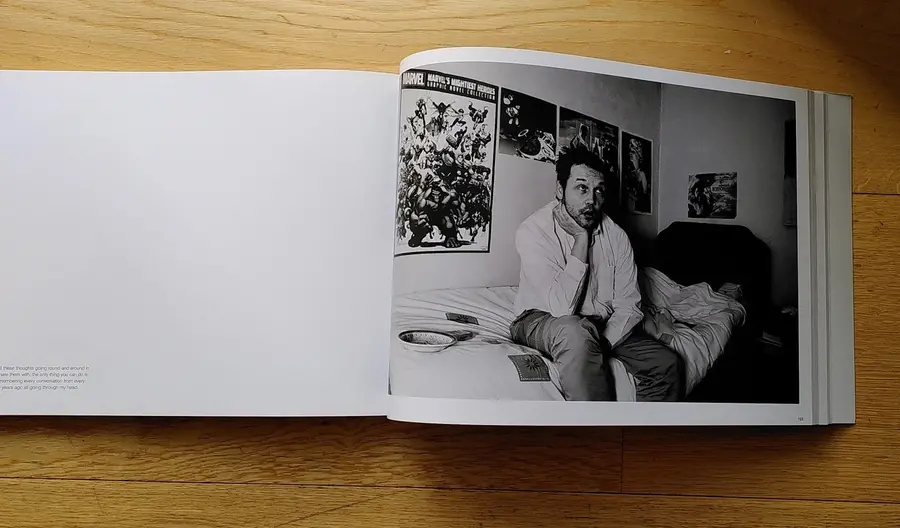

Loneliness is a persistent theme, and Mortram’s decision to photograph in black and white entrenches feelings of alienation in an aura of authenticity amidst a world overwhelmed by numbing colour stimuli. We are entirely absorbed in their worlds without the distraction of colour, roped in by minute particulars that establish a shared sense of humanity. Indexes of the highly personal naturally draw our eyes; focal points become facial expressions, posters on walls and objects on bedside tables, incorporating the reader into the folds of the pages themselves.

Hanging over Small Town Inertia is the long dark shadow of austerity and the resulting cuts to social care, a political sacrifice of one of the United Kingdom’s most vulnerable groups of people to counterbalance the losses of the most privileged. Mortram’s presentation of Dereham effaces the all too familiar tropes that serve as part of a broader political apparatus that stigmatises people relying on benefits. His photographic ‘subjects’ are barely ‘subjects’ at all and excerpts of conversations between Mortram and the sitters accompany most photographs. Thus, Small Town Inertia becomes an act of reclamation, restoring authorship to people whose stories mass media established in discourses of collective laziness.

There appears to be a perpetual sense of Mortram in the photographs. His deep connections with Dereham and his role of full-time carer to his mum gives him license to identify with the people he photographs. At the same time, Mortram’s presence is not overbearing. The people he photographs are autonomous, clever, acutely aware of their position, and Small Town Inertia manifests as a collaboration between the two. What Mortram’s subtle omnipresence does is let us engage with the conversations as they are revealed, temporally fragmented, seemingly both in the past and as life happens. This illusion means we enter the books with ease. Our own imagined conversations are somewhat unsettling. Such is the emotional complexity of Mortram’s photos that we reflect on our own position in relation to the people of Dereham, and you can’t help but feel personally complicit.

- Josephine Ellis