‘Everything was on the move’

Michael Kustow, director of the ICA, 1968–1973

In 1967 Sue Davies was thirty-four years old and living with her husband, jazz musician John Davies, and their children in Buckinghamshire. She was working when Julie Lawson offered her a job the Institute of Contemporary Arts. Davies was an experienced arts administrator and manager and by then she was adept at juggling a full and lively family life with an energetic and committed approach to her work so she eagerly accepted Lawson’ offer. It was a decision that would lead her to open London’s first ever non-commercial photography gallery three years later – aptly named The Photographers’ Gallery.

The ICA in flux

The ICA was entering a period of change and financial duress when Davies joined as a member of a new team brought in to manage the Institute’s move from its first venue in Mayfair to the heart of central London. The ICA founders, poet and art critic Herbert Read and Surrealist painter and collector Roland Penrose were both wealthy philanthropists and determined to be free of official funding so the ICA was set up as a foundation, Living Arts Ltd, with charity status that was almost immediately freighted with an on-going search for patrons, sponsorship, and increased membership. At the inaugural exhibition in 1948 Read described their vision of an ...’adult play centre, a workshop where work is joy, a source of vitality and daring experiment’. The Institute’s hallmark exhibitions nourished cross fertilisation in the arts and sciences with a lecture and discussion programme accompanying each exhibition. This resonated for artists in post- war London and the ICA was quickly heralded as the most avant-garde organisation in the capital. It was also the earliest venue to show and discuss photography and it held the dialectic on photography in the 1950’s and 60’s, alongside the Slade School of Art.

A profound change in the arts in the 1960’s prompted the Institute’s management to reconsider its structure and exhibition programme. As this tallied with the expiration of the Mayfair lease the organisation decided to relocate. The Arts Council, its key funder, pressed the ICA Management Council to move into Nash House, a spacious and vacant building on The Mall. Under Wilson’s government this period is perceived as a golden time for arts funding, with Lord Goodman as chair of the Arts Council and Jennie Lee as Minister of State for the Arts. But there were shortcomings. The Arts Council grant was £400,000 less than the ICA’s ambitious exhibition and event programme had planned for its prestigious new venue.

The ICA reinvents itself

It was January 1968, a couple of months before the ICA’s relocation, that 28-year-old Michael Kustow left the Royal Shakespeare Company to succeed the ICA’s director, zoologist Desmond Morris. Davies considered Kustow ‘just a kid’ – but much later she acknowledged that ‘the ICA was always reinventing itself, it was always dependent on its director, and she observed how Kustow ‘knew how to work people – and the press.’ His sharp intellect and voracious appetite for the arts was to prove invaluable.

By 1968 ‘Swinging London’ was long deflated and the optimism sparked by the re-election of Harold Wilson’s government in 1964 was drained by the devaluation of sterling in 1967 and an international monetary crisis in 1968. Wilson had promised a new and confident Britain, which failed to materialise, Kustow was savvy and knowing that contemporary art had become attractive for sponsors he planned to develop sponsorship as an important income strand.

‘It was an exciting time’ Davies recalled ‘and things happened’. Visitor numbers grew exponentially, attracted by the location, the café, the bar, the cinema/auditorium and a new membership structure that made the ICA financially accessible for a larger and more diverse audience. Wealthy members and patrons were drawn to the Regency elegance of 12 Carlton House Terrace situated above Nash House, with its bar, dining and clubrooms. But funding issues remained rife and the end of his first year as director Kustow wrote ‘...we are not in intention, or by the level of our subsidy, an amenity institution like the Tate or the Royal Festival Hall.’

A confidential memo from the newly created Programme Group to the ICA Executive Council in November 1968 outlined the situation. ‘We have no money to pay for the £11,800 deficit from the Japanese exhibition; the rent; next week's wages; and the hundreds of pounds of furniture being ordered for the new offices.’ A list of nine emergency steps followed. Kustow wrote a crisp letter to the Arts Council pointing out the impossibility for any temporary exhibition, however successful, to cover its real costs, which included rent, services and overheads. He then prepared a report in response to the Executive Council’s demands for low-budget exhibitions with guaranteed costs.

Exhibitions

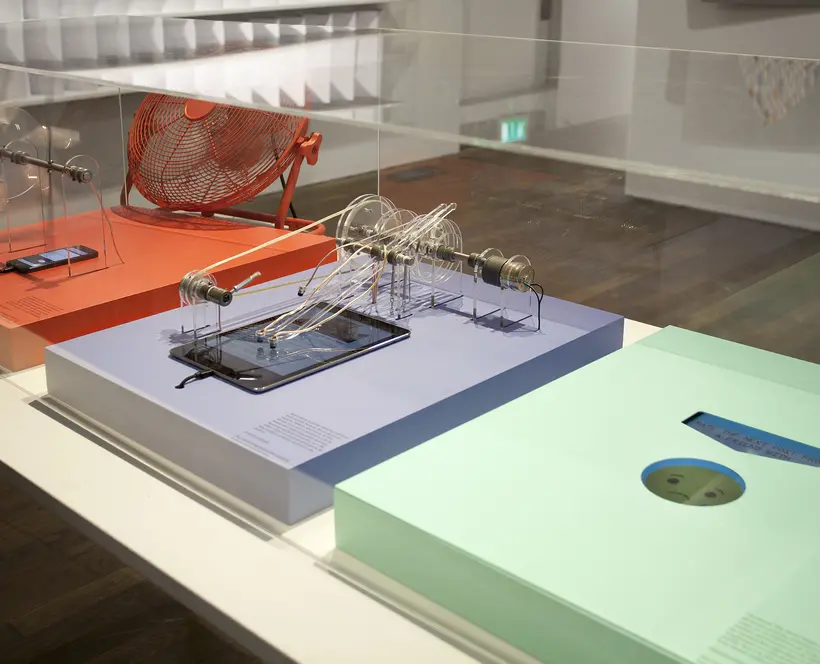

The director was well supported by the Programme Group and the four women who formed the exhibition team. Lawson had joined the ICA in the 1950’s and was appointed deputy director after the relocation. With a long ICA career she was a management linchpin, much liked her for her empathetic manner and natural charm and she invited Davies to work with her. Reichardt had worked at the ICA since 1963 in a role that would be understood now as curatorial. She was interested in the intersection of the visual arts and science and her ground-breaking exhibition Cybernetic serendipity: the computer and the arts in 1968 received rave reviews and drew and intrigued an enthusiastic and diverse audience, including children. Computers were rare then and the exhibits, created by computer scientists, poets, musicians and poets as well as artists, intrigued an enthusiastic and diverse audience, including children. It continues to be recognised as a pioneering show.

Reichardt followed it in the winter of 1968 with The Fluorescent Chrysanthemum, which showcased contemporary Japanese art, music, film and design – work that had never been seen in Europe before. Although Reichardt was expanding the notion of contemporary art, which the ICA, empowered by the Arts Council, was funded to show, the costs of these two exhibitions finally triggered the impending financial crisis.

Spectrum: the diversity of photography

Kustow had four months to conceive develop and install an exhibition and a programme events and he relied on Davies’ administrative and management skills to make it happen. Juliet Brightmore, who worked with Reichardt, described Davies in the parlance of the day as ‘the senior chick, running the show’. A shift in contemporary art at the end of the 1960’s led to the integration of photography the work of emerging sculptors, film into performance art and the appropriation of photographic imagery into Pop Art. Kustow acknowledged the ICA hadn’t explored this significant change and he set out to ‘open up the concerns and situations of photography today’. Spectrum: the diversity of photography was announced as the ICA’s first big photographic manifestation. It was conceived as five separate exhibitions with a concurrent programme of discussions, lectures and a film festival.

Woman, a touring exhibition sponsored by the German magazine Stern, was the largest of the five. The vast new gallery space could accommodate the five hundred photographs and Stern was providing the funding. It was heavily mediated in the style of The Family of Man and Kustow gave Davies a three-day deadline to oversee the installation, which she achieved. Twenty years she described it as ‘monstrous...blow-up photographs of women, largely taken by men, dry mounted in two parts onto large panels’.

Kustow proposed four small exhibitions of contemporary work as a counterpoint to Woman. He was confident he could pull it together. He eschewed fashion, advertising and reportage, which were predominantly disseminated in magazines and newspaper colour supplements. ‘I'm a rapacious person’ he said. It's part intuition, part network and part asking. You learn to trust your contacts.’

In a time when social medium was unimaginable, meetings, phone calls, letters, and left field thinking was essential. Kustow quickly discovered a recondite magazine Creative Camera and learned there was a discourse about photography. The editor Bill Jay was an inspirational writer, lecturer and photographic historian. He was also provocative and unpredictable. Kustow invited him to be one of his advisors, knowing that Jay could introduce him to more.

Four Photographers in Contrast

Photo-graphics, The English Seen, The Destruction Business and People at Peace revealed photography’s appositional relationship to contemporary art. Kustow selected four photographers, and paired them in two consecutive exhibitions, Enzo Ragazzini with Tony Ray Jones and Don McCullin with Dorothy Bohm. They each exhibited their personal work. When Kustow and Davies visited Ragazzini’s studio he realised they lacked experience with photographers and photography. ‘They just looked at my work’ he recalled later ‘and said “great, great!” We were allowed up to thirty prints each and because Tony Ray Jones’ prints were so small I had a wonderful space. Nobody asked us what we was going to show’. After Davies founded The Photographers’ Gallery, Ragazzini spoke of his admiration for her and gave her several of his prints for the first fundraising auction at The Photographers’ Gallery in 1971.

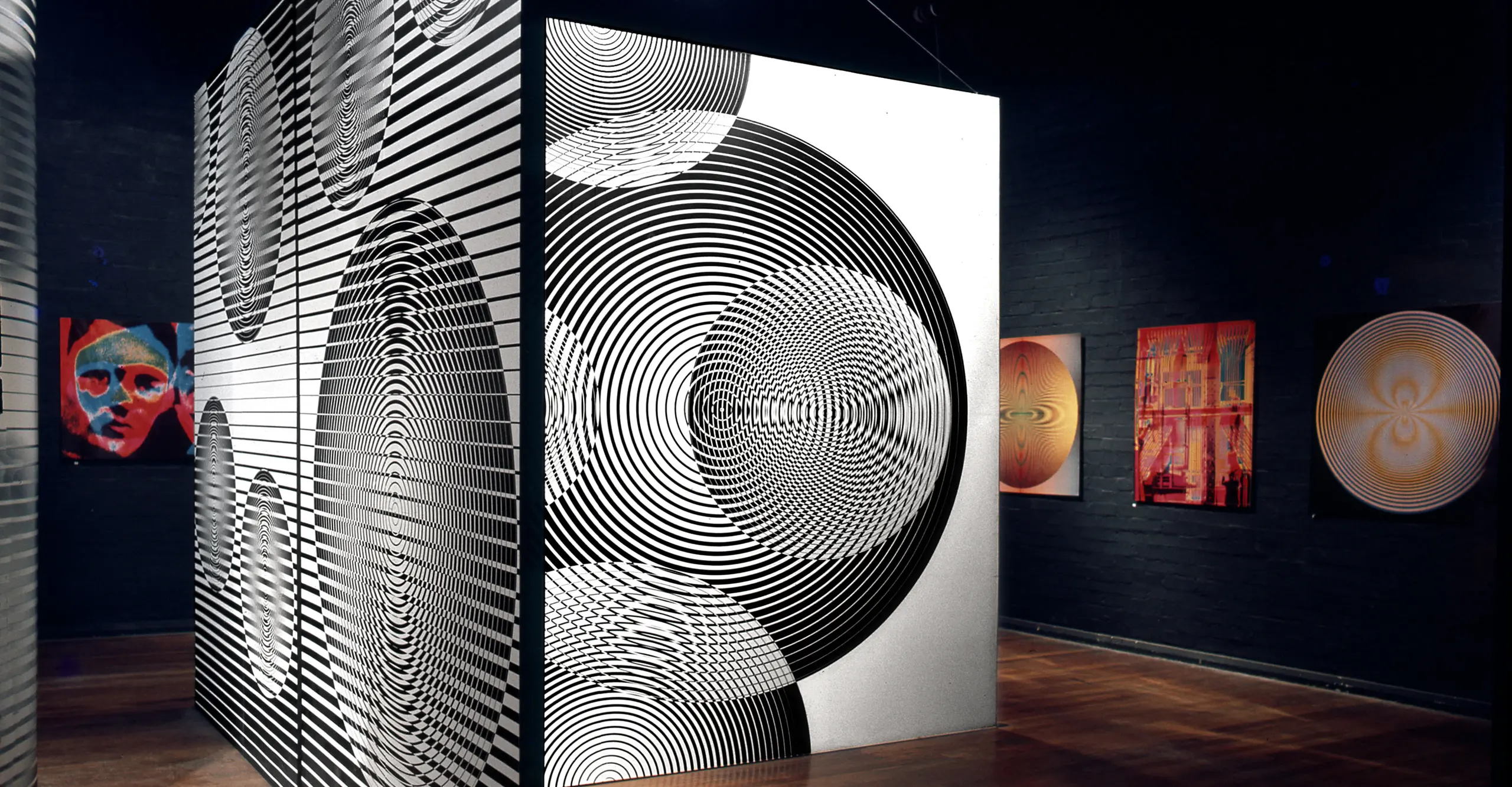

Photo-graphics

Ragazzini created a dynamic installation for his huge optical abstracts, revealing that the darkroom could be a creative as well as a technical space. In the early, pre-Photoshop, 1960s he used a variety of technique in colour and black and white, many of which many he had developed himself. His explorations resonated with Bridget Riley and Victor Vaserely’s investigations into light and the physiology and psychology of perception. ‘I was using the photographic language as a painter uses language,’ he said. He predated the painter Bridget Riley and like her, he described his process as an investigation. He was the only photographer to use colour, showing the first Cibachrome prints in the four exhibitions.

The English Seen

For his first exhibition in Britain Ray-Jones selected photographs from his two-year quest to rediscover his homeland. He had returned from New York three years earlier and began to meld the influence of Robert Frank and Cartier-Bresson, integrating it with American street photography to develop a quintessentially English approach to his visual essays. Ray-Jones’ work, his thoughtful writing on photography and his complex imagery enthralled Kustow. ‘This was someone with passion – and old humanist values’. Ray-Jones was an important conduit to American photography thinking and a major influence on Bill Jay.

The Destruction Business

In 1969 McCullin he was working for The Sunday Times Magazine, the benchmark for art direction and journalism at the time. The Vietnam War overshadowed this period and he was renowned for documenting it. Creative director Michel Rand commissioned the majority of work McCullin’s and his searing images of conflict, shot in Cyprus, Cambodia, and Vietnam were included in The Destruction Business. The gallery wall stripped these photographs of their of political and journalistic narrative and hung alongside McCullin’s personal work they became potent icons.

People at Peace

In contrast to the other photographers Dorothy Bohm was an auteur. Penrose assisted her

with People At Peace, her first ever exhibition, structuring it as an essay with thematic motifs. Bohm was a refugee from Nazi Germany and her cultural sensibilities were informed by Europe rather than Manchester where she had studied and worked as a studio photographer. She nurtured her European affinities through frequent travel, which set her apart from British parochialism and the, then current, fixation with American photography.

Discussions, lectures and films

Spectrum opened on April 3 1969. It was one of three exhibitions that signalled a sea change in the institutional approach to photography at the end of the 1960’s. Roy Strong, the redoubtable young director at the National Portrait Gallery set the ball rolling in 1968 with a wildly popular and theatrical designed Cecil Beaton retrospective. Henri Cartier-Bresson, also a retrospective, was shown at the Victoria and Albert Museum, concurrently with Spectrum. All three exhibitions positioned photography in a fine art framework.

Spectrum was the outlier. The series of lectures and films took that took place during the exhibition in the cinema and auditorium between 3 and 11 April situated it in a discursive context. Five discussions and two lectures were linked thematically to the exhibitions and twenty-five leading artists, photographers, historians, and academics were invited to open up ideas about photography’s commodity value, its history and its relationship with art, film and social change.

Kustow chaired the opening discussion, The Compulsiveness of Photography, introducing Ian Berry, a documentary photographer and member of Magnum, David Montgomery and Brian Duffy representing fashion and Terry Fincher, the press. Academic and feminist polemicist Juliet Mitchell responded to Woman, together with two social psychologists, presaging photography’s intersection with the cultural and political debates that were to inform the 1970s. American academic Van Deren Coke lectured on the many diverse histories of photography and painting and the Open University Professor Aaron Scharf chaired the discussion that followed.

The Spectrum Film Festival ran simultaneously, showing twenty-eight films, selected for their relationship with photography. A vocal and lively audience crammed into the discussions and lectures, and queues ran down the Mall towards Buckingham Palace. It was a compelling programme but who actually took part is almost impossible to ascertain. Bill Jay recalled ‘we had no idea that what we were doing was important. We had no sense of posterity then’.

The ICA was reckless with its archive. There are few records of Spectrum, attendance figures, financial records and hundreds of missing audiotapes. The ICA’s press release was limited and as an event Spectrum is long overlooked. The majority of key players who were shaping or going to shape the photography world in the 1970s were attributed a role in the event. But memory is capricious and the prevailing memories of Spectrum are its role as a nexus and the buzz of the opening.

Peter Turner, assistant editor of SLR magazine, described it as ‘...a major, major event, not just in my life, but also for many people I knew at the time. The director of Oxford’s Museum of Modern Art in Oxford, Barry Lane, recalls his Damascene moment. ‘I wasn't living in London then, I wasn't part of what was going on. The idea of photography is bound up in what you see. It was the sheer diversity of Spectrum ... I didn't realise it could be so radically different, one photographer's work from another, Enzo's from Don's. I felt as if I was part of something important ... It gave credibility to an underground activity’. Spectrum galvanised a younger generation of photographers, the ICA itself and Davies.

After Spectrum

The ICA was eager to capitalise on its newly recognised interest in photography and the Programme Group initiated plans for future exhibitions. Davies wrote a proposal drawing on Aaron Scharf’s book Art and Photography, confident that the ICA had enough clout to loan the necessary paintings. Reichardt continued her interest in the intersection between the arts and science with Unlikely Photography, an exhibition that would demonstrate ways in which perception could be affected by various photographic techniques. This dovetailed with the contemporary ICA thinking and interested Kustow. The critical success of her previous exhibitions weighed in her favour and Kustow asked her to develop the ambitious proposal (though in the end the exhibition would not materialise). Publicly Davies blamed the rejection of Art and Photography on divisions within the Institute, and although she privately understood, she was angry and resigned.

Davies left the ICA in the autumn of 1970 determined to found a dedicated gallery for photography and photographers. It was a bold and financially perilous decision, driven by anger. Importantly she recognised that Spectrum signified a new cultural position for photography and although she identified herself as an amateur in terms of the medium, she trusted her instinct for ‘political texture and timing’. At Spectrum she met a vital and passionate photography community with nowhere to meet, talk or exhibit in London and beyond. Her three years experience at the ICA played a critical role in her plans. She knew

the importance of a central location; she had observed the financial machinations of Arts Council policy at that time and experienced the exigencies a charity had to deal with. Recalling the queues that stretched down the Mall for the lectures, films and exhibitions she knew she had an audience. ‘Photography was simple compared with Minimalism’ she explained ‘and people liked it. Nobody was frightened.’

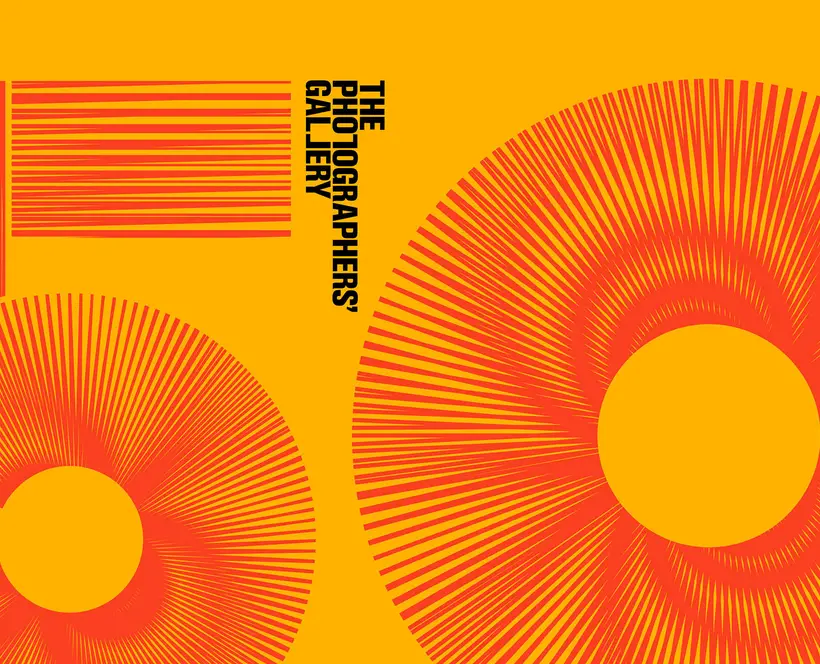

Contacts were myriad in the 1960s and at the ICA Davies had tapped into a huge and influential network. Lord Goodman wrote to Cecil Beaton and Tony Armstrong-Jones (later Lord Snowdon) on her behalf; Bill Brandt quietly slipped her £50*; and photographers, picture editors, journalists, editors, and Magnum, with its international reach, were all-important supporters. The indomitably Bill Jay advised her until they parted ways. With formidable energy, pizzazz and vital support from her husband, who agreed to re-mortgage their family home to fund The Photographers’ Gallery lease it opened on 14 January 1971, only three months after Davies left the ICA.

It was a remarkable feat, still applauded, and Davies was to become a key player in

the dissemination of photography in the 1970s, a fast-changing period for British photography.

By Anne Braybon

Anne Braybon has been an editorial art director, an independent consultant and photography commissioner for London’s National Portrait Gallery, and a creative director and curator for Arts Council national touring exhibition. She is old enough to remember Spectrum and many of those involved, as friends, interviewees and her photography tutor.