Min Kyoo Kim reviews Jane and Louise Wilson: The Toxic Camera on display at Maureen Paley Gallery and Studio M from 29 April – 5 June 2022

“… Shevchenko’s camera had become an actual lethal weapon requiring its immediate decommissioning and disposal.”

[Excerpt, The Toxic Camera]

Rarely in exhibitions of photography do we centre the image and story of the camera. By distinction, Jane and Louise Wilson’s multi-media installation The Toxic Camera (2022) expands on their 2012 documentary of the same name, an exploration of a filmmaker’s ill-fated attempt to record the nuclear disaster in Chernobyl. In so doing, and with an auspicious, sharpened focus on the conflict in Ukraine, the Wilsons present the camera as a compelling – even murderous – subject.

Room One: The Toxic Camera

The Wilsons, with a well-established interest in “liminal zones of exclusion”, aptly stage two contrapuntal spaces inside the Maureen Paley Gallery: one, a black-box of a moving image installation, revisiting extracts from The Toxic Camera; the other, an immaculately mustard-yellow annex, which retrieves images and items from Cold War-era Chernobyl.

On entering the gallery, the sound of a Geiger counter – that scraping, insidious crackle – draws my curiosity to the film space. Adjacent to the screen are mirrored panels, displaying scenes of the Chernobyl exclusion zone – abandoned houses, factories, parks – replicating themselves beyond the frame. This elongating patchwork of environmental disaster relays, perhaps, how the creep of radiation evades any circumscription, all horizons; it’s as if the camera, contaminated by the nuclear past, spawns and spreads radioactivity in the present. This cancerous temporality, The Toxic Camera announces, is what killed Vladimir Shevchenko, the filmmaker who sought to document the events of the Chernobyl disaster. The irradiated, corrupted footage shot on Shevchenko’s camera embodied the very contagions that claimed the director’s life. This story, the experience of seeing and hearing it, is moving as it is acutely unsettling.

Room Two: Konvas Avtomat

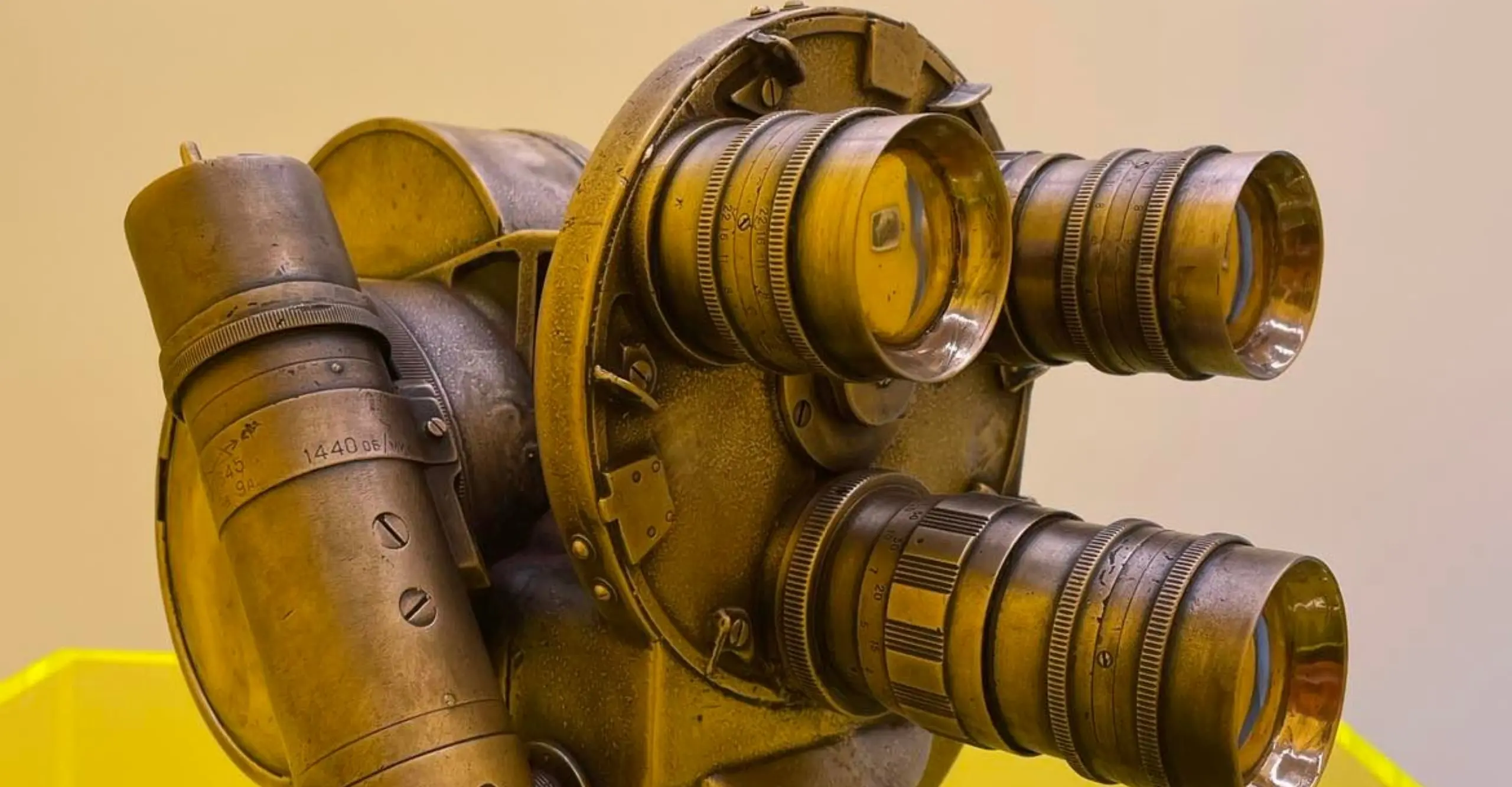

Stationed atop a Perspex plinth in the mustard-yellow room, I find the eponym of this exhibition, Shevchenko’s “toxic camera”. Replicated in a bronze-cast model, the Konvas Avtomat – a 16mm multi-lens camera, with a spinning mirrored shutter – bears an uncanny resemblance to a gas mask. This likeness evokes, in the jaune light of the installation, a morbid irony; far from mitigating against radioactivity, the Konvas had actually captured, even incubated, the pernicious particles – such was the extent of this contamination, that the Konvas had to be buried outside Kyiv.

It’s thus unnerving, if beguiling, to stare at this model of the Konvas, and see my reflected image dispersed across its tripartite, golden gaze. Does this camera, with its index of contamination, register the stoic courage of Shevchenko and his crew? Or is it that I personally feel vulnerable, almost bare, in the penetrative glare of this infected kino-eye.

The power of the exhibition resides in staging this poignant, meditative encounter with the nuclear, while foregrounding the role of the Konvas, this “toxic camera”. Beyond the compelling nature of the artworks, it is the parsimony of curatorial intervention, which opens this polysemous, yet emotive, space to both interpretation and reflection. Perhaps it is such presentations that connect art to a more politicised praxis – an urgent, moral need in a world where the nuclear horizon continues to loom.

Written by Zoe Boutte