What is photopoetry? Its neglect is such that the Oxford English Dictionary records no definitions of ‘photopoetry’ or ‘photopoem’, or comparable terms such as ‘photoetry’ or ‘photoverse’. Such terms do exist, however, and the first use of the word ‘photopoem’ occurs in Photopoems: A Group of Interpretations through Photographs (1936), photographed and compiled by Constance Phillips. Pairings of poems and photographs in book form had existed for almost a century prior to Photopoems, though Phillips’s anthology is important for its suggestion that the form deserved to be recognised and given a distinct name.

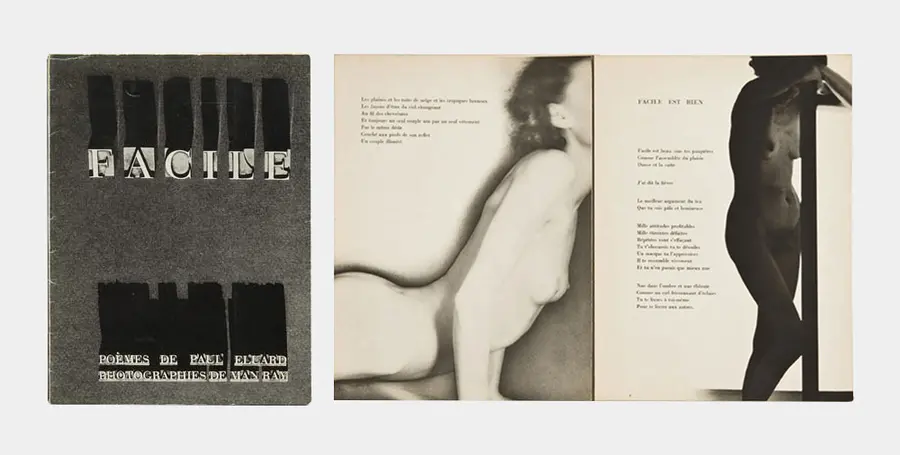

In adopting the term, I do not mean to privilege photography over poetry in my conception of these collaborations; I choose it because, of the few terms used to define the relationship between poetry and photography – in both practice and criticism – it is the most common. That said, critiques and theories of photopoetry are few and far between. In her article on Paul Éluard and Man Ray’s Facile (1935), Nicole Boulestreau invented the term photopoème to describe the slim volume combining Éluard’s poems and Man Ray’s photographs.

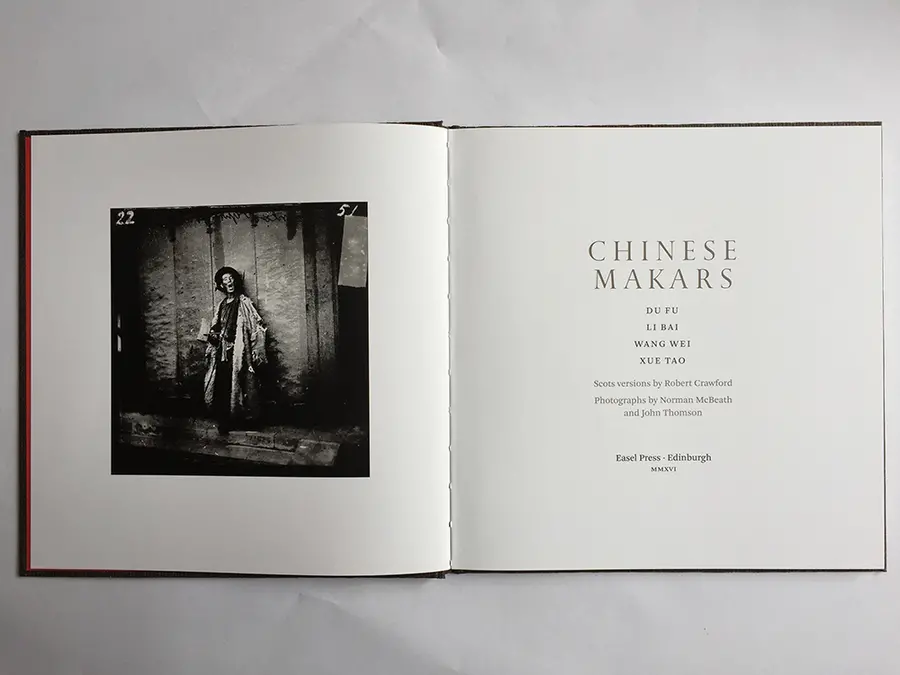

"In the photopoem," writes Boulestreau, "meaning progresses in accordance with the reciprocity of writing and figures: reading becomes interwoven through alternating restitchings of the signifier into text and image." [1] Poem and photograph encounter each other, and Boulestreau appears to suggest that the photopoème should be defined, not by its production, but its reception, as a practice of reading and looking that relies on the reader/viewer to make connections between, and create meaning from, text and image. Against these ‘restitchings’, Andy Stafford uses the term ‘photo-poetry’ to describe the ‘tightly linked (though not fused)’ images and texts of Philippe Tagli’s Paradis sans espoir (1998), though he prefers ‘photo-graffiti’ as a conceptual label for Tagli’s work. [2] Most recently, Robert Crawford and Norman McBeath have included ‘Photopoetry: A Manifesto’ in their collaboration Chinese Makars, a book where Scots versions by Robert Crawford of work by four poets or ‘makars’ from the classic era of Chinese poetry are paired with black and white duotone photographs by Norman McBeath and the pioneering Victorian photographer John Thomson (1837 – 1921).

Their twelve points range from the dependence and interdependence of poems and photographs; the importance of ‘revealing’ in order to ‘[engage] the reader’s imagination’; the need for a variety of connective strands between text and image; and, first and foremost, an assertion that ‘Poems and photographs encourage each other’s obliquity.' [3] Literal illustrations and descriptions are not engaging, according to Crawford and McBeath, and they suggest that the relationship between poetry and photography, at its deepest and most engaging, is serendipitous and requires the reader/viewer to reach, work, and imagine in order to make productive connections between text and image.

Indeed, Crawford and McBeath’s Chinese Makars is an artist’s box combining McBeath’s photographs with a new version of Crawford’s translation of The Dream of the Rood, one of the oldest known works of English literature. Reaching from one language to another echoes the reach required to connect poem to photograph, photograph to poem, in that connections are not necessarily obvious. Translation is a more generous model than illustration, allowing for relationships that are not perceived as definitively literal or descriptive. Oftentimes, a particular tone or spirit is sought, and the egotism of the translator can emerge in the avoidance of obvious literal equivalents. The poem Stravaigin Saurs: Easie-Osie (Wandering Winds: Lazy) reads:

Easie-osie, wi nae wey o daein,

Ah dinnae gang ayont the clachan,

But cry tae ma laddies i fair daylicht,

‘Pu the hingers.’

Amang blaebells wi a guid dram

Wuids wud be lown –

Spring wunds oan skinklin burns –

Ootby this gloaming.

Lazy, with no job, I don’t go beyond the vil-

lage, but call out to the boys in broad day-

light, ‘Pull the curtains.’ Among bluebells

with a good dram woods would be peaceful

– spring winds on shining streams – outside

in this twilight.

The Scots poems of Chinese Makars are printed not with the original Chinese poems but alongside English glosses which, for the reader unfamiliar with Scots, serve further to complicate the relationship between poem and photograph.

What, then, are the advantages of considering photopoetry as a distinct form of photo-literature? What does poetry bring to photography that prose, for example, does not? I would argue that, in most of cases, poems and photographs function as self-contained realities. They are, at first, separate, whole. As John Fuller writes, a poem is "gradually constructed in words and images that has to pass muster as an alternative reality. But the photographer is exploiting reality itself, almost directly." [4] Both are concerned with images: the visual immediacy of the photographic image against the unravelling, modifying, accumulating verbal images that emerge from the poem. In conjunction, such visual and verbal images blend, clash, contradict, embolden, evoke, and resist each other, creating photopoetic images that seem, in Crawford and McBeath’s terms, to encourage the ‘obliquity’ and ‘serendipity’ of text and image.

MIchael Nott is a Postdoctoral Fellow at University College Cork, Ireland. His book Photopoetry 1845-2015: A Critical History is published by Bloomsbury in 2018.

[1] Nicole Boulestreau, ‘Le Photopoème Facile: Un Nouveau Livre dans les années 30,’ Le Livre surréaliste: Mélusine IV (Paris, 1982), 164.

[2] Andy Stafford, Photo-texts: Contemporary French Writing of the Photographic Image (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2010), 156-158. Two chapters in Photo-texts explore poetry and photography in the work of Tahar Ben Jelloun (106-121), and Philippe Tagli (156-168).

[3] Robert Crawford and Norman McBeath, ‘Photopoetry: A Manifesto,’ in Chinese Makars, by Crawford and McBeath (Edinburgh: Easel Press, 2016), 68-69.

[4] John Fuller and David Hurn, ‘A Conversation by Way of Introduction,’ in Writing the Picture, by Fuller and Hurn (Bridgend: Seren, 2010), 8.

This article is a co-publication with Photocaptionist