"...bars cannot hold me, force cannot control me..."

Bob Marley

One afternoon in 1973, teenaged photographer Dennis Morris and soon to be global superstar Bob Marley were sitting, reasoning and smoking. Marley jumped up and said, ‘let me show you how to be free, Dennis … bars cannot hold me, force cannot control me, I-man a rebel.’ Morris, knowing this to be a cue, quickly drew for his camera. The resulting photos are some of the most intimate ever taken of Bob Marley, with him grinning, jumping around and playing with his hair, showcasing Marley’s playful side in a way that other photos of Marley were unable to capture.

In many ways, this small exchange can be seen as a metaphor for the cultural impact of Rastafari on Black Britain; Rastafari showed Black Britain how to be free.

With origins in 1930s Jamaica, Rastafari is a spiritual, social and cultural movement, rooted in the fight for global black liberation. Rastafari has a deep history and philosophy, centred around the divinity of Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia. The movement emphasises African unity, repatriation to Africa and the rejection of colonial oppression, and promotes natural living grounded in African identity.

Britain has always been a hugely important location in the geographies of Rastafari. Britain is seen as an embodiment of ‘Babylon’, a corrupt oppressive system of colonialism, materialism and exploitation, the antithesis to the livity Rastafari promotes. Haile Selassie also famously lived in Fairfield House in Bath from 1936-40, while in exile during Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia.

Following this, Rastafari would go on to have huge implications on the development of British society. The earliest Rastas in Britain arrived in the mid-1950s, when the United Afro West Indian Brotherhood’s Rafael Downer and the Ethiopian Youth Cosmic Faith’s Brother Edie travelled from Jamaica. Their main concern was the repatriation of the Rastafari community to Ethiopia, however they sowed the seeds of the movement in Britain that would go on to affect the politics, spirituality and identity of Black Britain. Rastafari’s most visible impact however was on Black British art and culture.

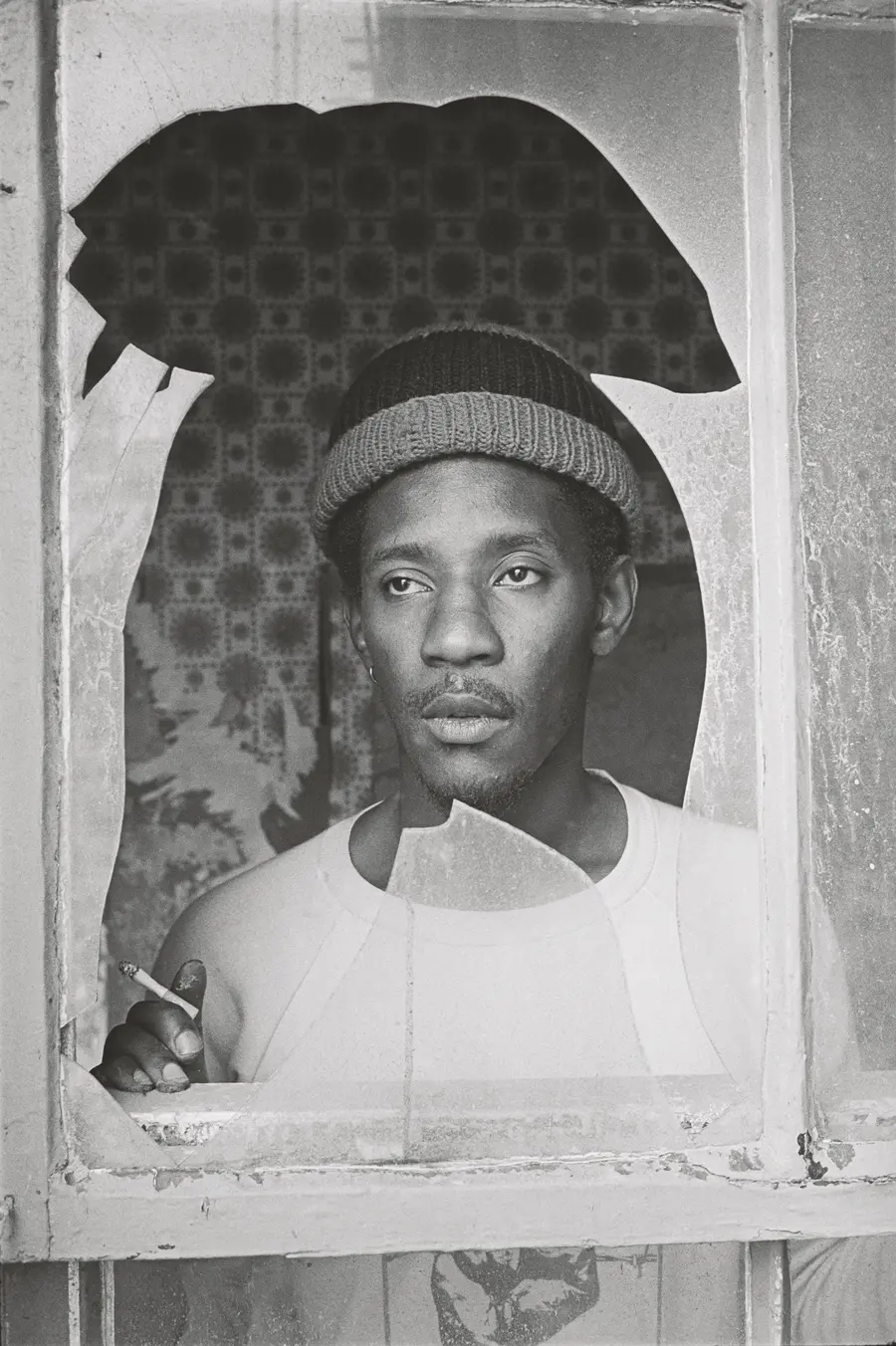

By the mid-1970s, when Dennis Morris first started shooting, the first generation of British-born Black youth were coming of age in a society they were born into but actively rejected by. Across the country, tensions ran high between Black communities, their white neighbours and the police. For some, Rastafari provided not only a means of fighting this injustice, but also a community to which they could attach themselves, and so naturally Rasta took up an important space in this emerging culture.

Rastafari music, in the form of roots reggae, got its first British flavour in the 1970s. Bob Marley famously recorded parts of his ‘Catch A Fire’ album, and subsequent albums, in London, however the emergence of bands such as Steel Pulse, Aswad and Misty in Roots set the wheels of British Reggae in motion. These bands carried the message of Rastafari, but applied them to the specificities of living black in Britain. ‘Handsworth Revolution’ by Steel Pulse was written as a call to action and a critique of the injustices faced by their community in Handsworth, Birmingham, and likewise Aswad songs such as ‘Three Babylon’ chronicle the band’s experience with the Metropolitan Police.

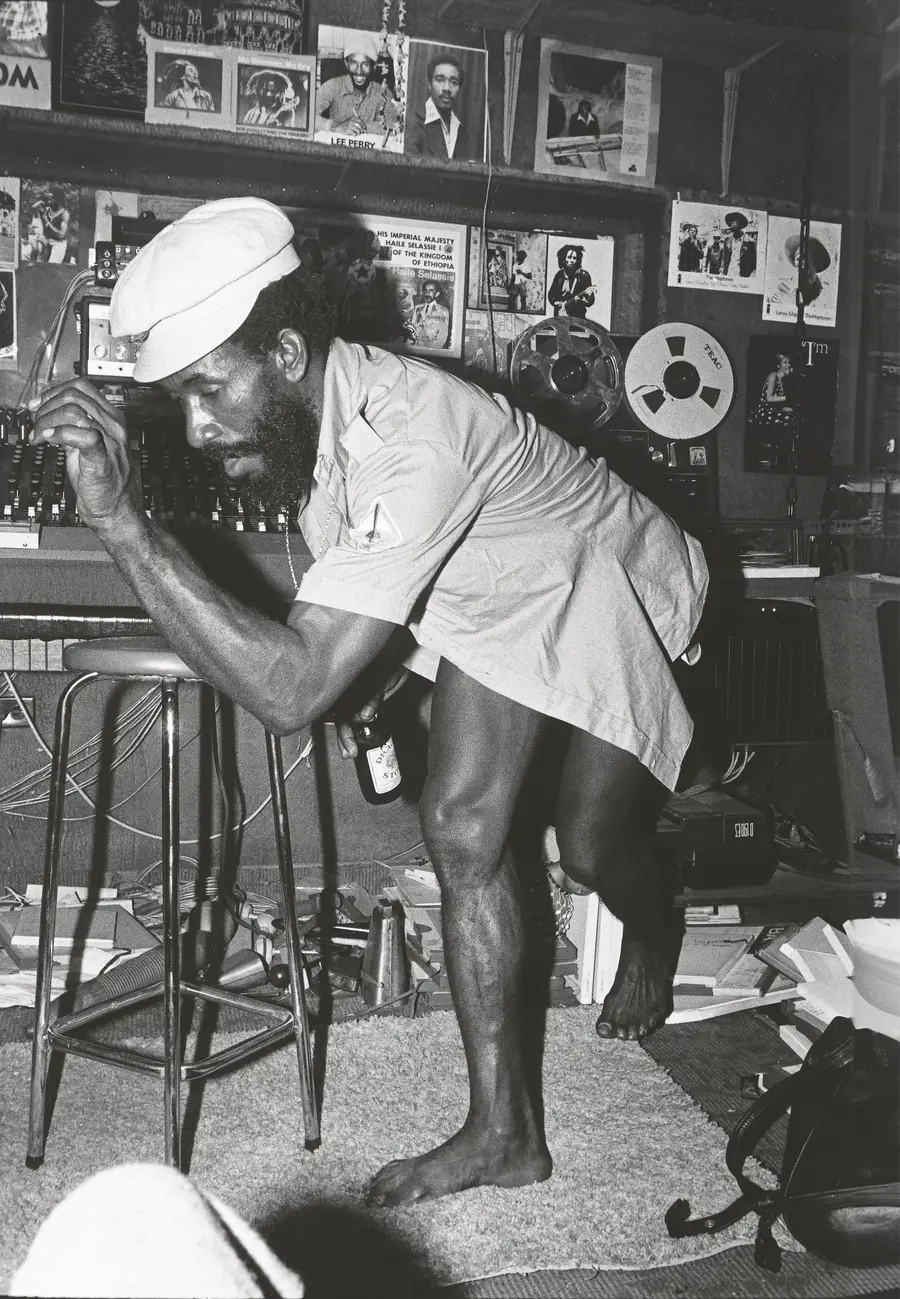

The popularity of bands like Steel Pulse and Aswad, alongside the continual import of reggae records from Jamaica saw the sound system become the voice of black youth across Britain. Pioneers such as Jah Shaka, who helped to usher in the dub age, made sure to keep the message of Rastafari ringing in the ears of the people. More concerned with charging up the community than playing the hottest records, Shaka was able to entice his audiences into a trance-like state, with his unique style of manipulation of spiritual reggae recordings and cries of ‘Jah, Rastafari!’

Sound system culture was also the focus of Franco Rosso’s 1980 cult classic film, ‘Babylon’, which starred both Aswad frontman Brinsley Forde and Jah Shaka. It follows the members of the Ital Lion Sound System and chronicles their life in Thatcher-era South London, navigating police brutality, racism and disillusionment, and provides intricate details of London’s sound system scene. Throughout the film, Rastafari acts as a force guiding the film’s main character, Blue, through the challenges he faced, and the film is anchored on a scene in which Blue finds himself at a Rastafari gathering and is reminded of the true message of Rastafari.

Elsewhere in film, the 1980s saw the production of groundbreaking documentaries which highlighted the particularities of the Rastafari experience in Britian. Barbara Blake Hannah’s 1982 documentary, ‘Race, Rhetoric, Rastafari’, highlights the understanding of Rastafari’s role in Britain from not only Rastas in Birmingham and London, but also from white members of these communities. D. Elmina Davis’s ‘Omega Rising: Women in Rastafari’ (1988) gives an account for the multi-faceted experiences of Rastafari women, both in Britian and Jamaica, giving voice to a group who had largely been ignored in narratives of Rastafari.

1978 saw the release of dub poet Linton Kwesi Johnson’s first album ‘Dread Beat an’ Blood’ as a member of the outfit Poet and the Roots. This album set the tone for LKJ’s career, being heavily critical of the British state and pushing the message of Rastafari, which would see him go on to release songs such as ‘Street 66’ and ‘Inglan is a Bitch’. Benjamin Zephaniah carried on the work of LKJ, producing similarly charged poems and advocating for change in British society.

Following a slight retreat from the forefront of Black British culture, in recent years, interest in Rastafari has experienced a resurgence. Dub nights have once again become popular, and sound systems like Channel One, Iration Steppas and Jah Youth are keeping the Rastafari anthems of reggae’s golden era relevant to the youth of today. In 2020, Steve McQueen released ‘Small Axe’, a series of five films centred around the experiences of West Indian immigrants to London from the 1960s to 1980s. Rastafari’s influence on Black British culture at the time can be seen throughout in the characters, language and fashion of the films, and today in fashion, designers such as Nicholas Daley and Grace Wales Bonner have looked to the iconic style of British Rastas in the 70s and 80s as inspiration for their pieces.

From its humble beginnings in rural Jamaica less than 100 years ago, the cultural impact of Rastafari has touched the whole globe. Rastafari has meant different things to different communities around the world, but for Black Britain, Rasta represented and continues to represent, an identity, a connection to home, a framework to interpret reality, an artistic inspiration and a pathway to freedom.

This text was commissioned by The Photographers' Gallery on the occasion of the Dennis Morris: Music + Life exhibition and the live programme Inside Out: Sounds of Reggae.

Get to know the writer

Commissioned Writer - Luke Bacchus

Luke Bacchus is a musician and researcher from London. One of the most exciting emerging artists in the UK's jazz scene, Bacchus explores his Guyanese and wider Caribbean heritage as the foundation of his music. His unique sound, a combination of Jazz and Caribbean Folk traditions, supplemented by his academic studies of the region's culture and history, which earned him an MA in Caribbean and Latin American Studies from UCL in 2024, has gained him fans the world over. He is a multifaceted cultural ambassador of the Caribbean, whose aim is to counteract the often one-dimensional representation and understanding of the region's rich cultural scene.

With special thanks to HOUSE OF DREAD.

HOUSE OF DREAD is an anti-disciplinary heritage studio dedicated to preserving and reimagining histories connected to the African and Caribbean diaspora. Grounded in co-production and community knowledge(s), the studio challenges dominant narratives, provokes new ways of thinking, and nurtures creativity. Through curated events, exhibitions, mentorship, and research-led programmes, HOUSE OF DREAD brings forward the rich, complex stories of people, places, and movements that have been overlooked, under-researched, or erased.