an incredibly beautiful and intelligent selection of works that make this [exhibition] both a pleasure and an education.

Stefano Basilico - Time Out New York

American colour photography of the late 70s and early 80s lies at the heart of Overnight to Many Cities, but rather than beginning here, in the middle, I'd like to start talking about colour photography before it existed.

Between 1935 and 1942 the US government, under the auspices of the Farm Security Administration (FSA), sent photographers around the country to document life in the communities hit hardest during the Depression. Jack Delano, Russell Lee, Marion Post Wolcott and John Vachon, among others, created more than 77,000 still images. The FSA pictures are a strange mix of modern reflection and antiquity. Perhaps this is because they were commissioned as documents by a government trying to define and track poverty before disenfranchisement entered the arena of political discussion. What makes them modern, almost like performance, is the sitters' utter lack of self-consciousness before the lens. The family in front of Russell Lee's camera might as well be a video grab. Their image is so clear and alive and open, as though they'd never had a mirror, let alone a picture of themselves, to look at before.

In 1936, Kodak released a new product: Kodachrome colour transparency film for 35mm still photography. At this time, colour was used almost exclusively in the worlds of advertising and glossy magazines. With its over-saturated and surreal palettes, colour photography was viewed as a strictly commercial pursuit. (According to Walker Evans, who had himself been working for Fortune magazine since 1934, colour was "vulgar"). Black and white remained the preserve of 'serious' documentary photography. However, some of the FSA photographers, though continuing to print in black and white, also had access to Kodachrome film. While they obviously saw in colour through their camera lens, their photographers' eyes were trained to translate everything into shades of grey. Now, for the first time, they were getting what they were seeing - without ever having seen it. This was a good 30 years before colour became a subject, a concern, within photography. And exactly 42 years before Sherrie Levine began appropriating and framing Walker Evans' FSA-era photographs.

In 1984 I began a part-time job as print registrar at Light Gallery in New York, once the bastion of 70s and 80s 'straight' photography. That was when the term 'straight' photography implied that your photograph was not appropriated from elsewhere and that it wasn't quite 'art', but something documentary, which therefore - it being the post-modern 80s - was fraught with questions of misrepresentation and exploitation. The bulk of my work at Light Gallery centred around a special portfolio of FSA colour dye-transfer prints. Up until this point, New Deal-era pictures were seen either in books, or as vintage black and white prints. It was the first time I had seen the indigo blues of kids overalls and the faded pinks of Sunday-best dresses. Until then, I had only seen poverty in black and white: still images from The Grapes of Wrath.

At the centre of Light Gallery, in a viewing room, was an immense set of flat files. Photo galleries didn't have racks, because nothing was framed before or after a show and everything was 20"x24" or smaller. There was a drawer of work by Harry Callahan - cool studies of his wife Eleanor, and dye-transfers of street work. Many drawers were dedicated to the photo-abstractionist Aaron Siskind; rocks, walls, torn billboards and an oddly divergent series of boys diving. There was a drawer of Stephen Shore's French gardens and the always popular Richard Misrach landscapes of deserts and crowds gathering to watch something which might have involved a plane. There were probably twenty more drawers and as many photographers, including Charles Traub and Robert Heinecken. In one drawer was a set of pictures by William Larson. The one I will always remember was of the side of a house. The centre of the picture or the subject was a bright green house. For me, a student of Laurie Simmons, this picture did not exist. The closest thing to it was an unfinished Eric Fischl painting. But as a child of East coast suburbia, the notion that one could travel to suburbia to photograph was a strange one. I understood the sarcasm and slow sensuality of Fischl's boy with a house, but a photo of the house alone left me unmoved.

What makes a travel picture? The fact the photographer went to a foreign place or that that place is foreign to the viewer?

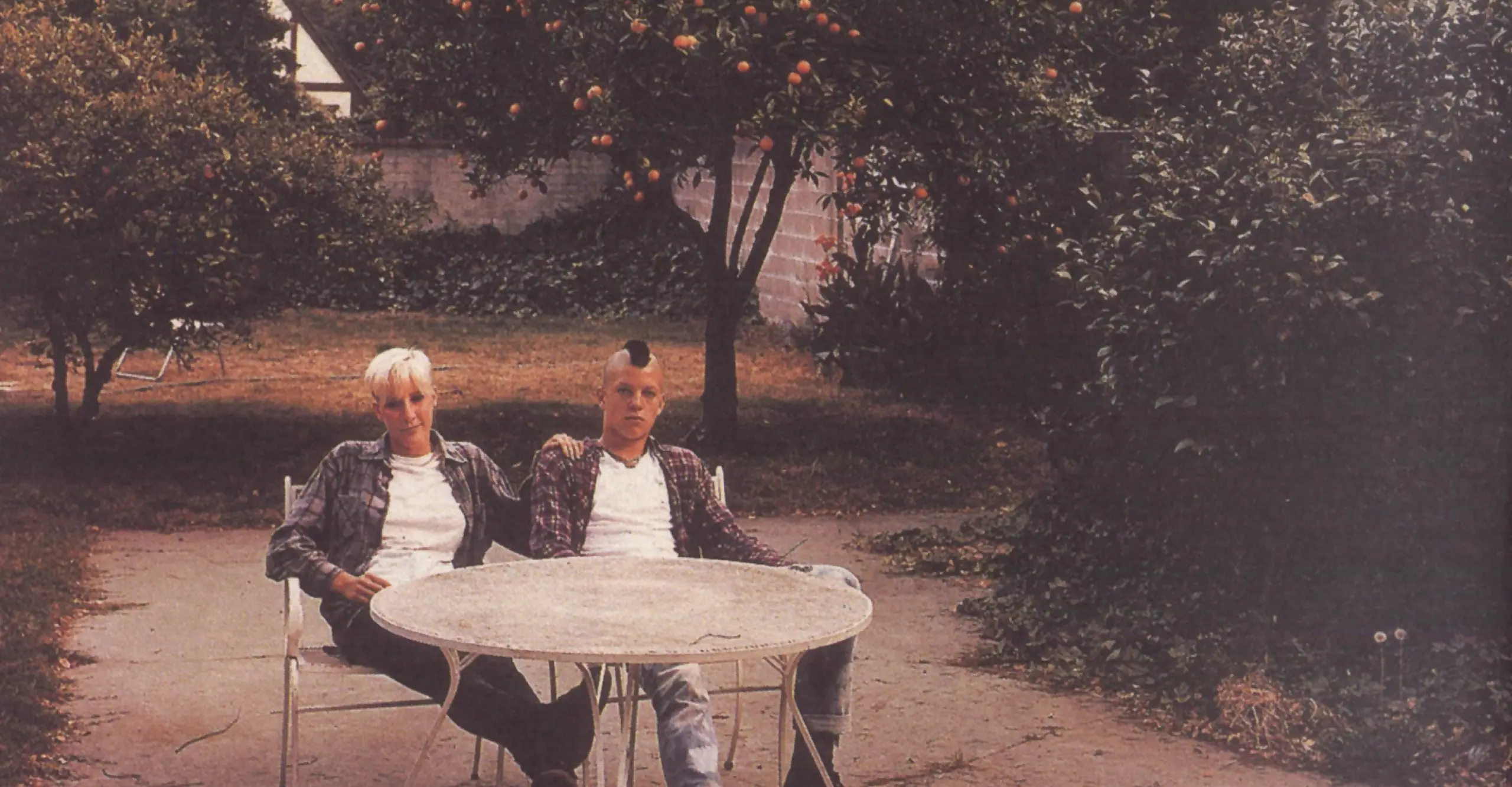

Everything I learned in the 80s told me that only poor people could and should represent one another. Martha Rosler's crucial Bowery (sans the alcoholics) series attested to that. The same went for people of colour and women. Anxieties about scopophilia, co-option and festishisation led to important writings and projects that took apart notions of the work of documentary photography. On the other side of the art world, however, straight photographers were beginning to parse out their roles. Some like Joel Sternfeld and Stephen Shore (who taught at the Kunstakademie in Dusseldorf) were pushing into suburbia, documenting something in progress that was completely the product of white male middle class growth, with none of photography's traditional interest in the disadvantaged and vulnerable Other. Yet, can images of suburban sprawl have political undertones? Just as we have invested post-war German photography with a social criticality, might we not look at the work of Americans like Sternfeld and Shore as highlighting the unfettered development of the post-Vietnam War suburbs? Hence, the exhibition's starting point is the mid-80s work of the New Colour photographers (Sternfeld, Shore, Meyerowitz and others). Artists working before or after this generation were chosen specifically for how their works played off of, or against, these historically crucial pictures. Seeking to expand how we look at the once bucolic notion of landscape and the results of the photographer's movement through it, Overnight to Many Cities challenges our ability to shuffle images as they bombard us in newspapers and magazines. Provoked by criss-crossing references and heavy doses of quotation, viewers have watched documentary projects beget cool distance and Post-modernist formalism. Colour studies lead way to a fascination with entertainment, and entertainment allows for social speculation. But rather than focusing on the inheritance of Hollywood, the artists in this show seem more connected to early 70s television (of made-for-TV movies that were peeling off the sheen of fifties romanticism) when the world was shrunken down in the American living room and photography was the same size".

Collier Schorr, Curator, Overnight to Many Cities

Special Thanks to: 303 Gallery, New York; Fern Schad, Light Gallery; DeCordova Museum and Sculpture Park; Gwen Darien; Howard Greenberg Gallery/Gallery 292; Klemens Gasser & Tanja Grunert Inc.; Laurence Miller Gallery; Luhring Augustine; Ariel Meyerowitz Gallery; Andrew Kreps Gallery; Pace/Macgill Gallery; Rose Gallery; Scalo Gallery, Zurich-New York ; Gallery Schedler; Jack Shainman Gallery; Brent Sikkema Gallery; Dennis Freedman; Gwyneth de Graf; University, Art Collection, New School University, New York; Charles Traub; Mario Sorrenti; Yancey Richardson Gallery; Lisa Spellman; Niel Frankel; Mari Spirito; Caroline M. Shepherd; Walter Cassidy; Kurt Brondo; Noam Rappaport; Amy McGrath; Simone Montemurno and Brian Doyle.

The Photographers' Gallery would particularly like to thank 303 Gallery, New York.

For further information on this and past exhibitions, visit our Archive and Study Room.