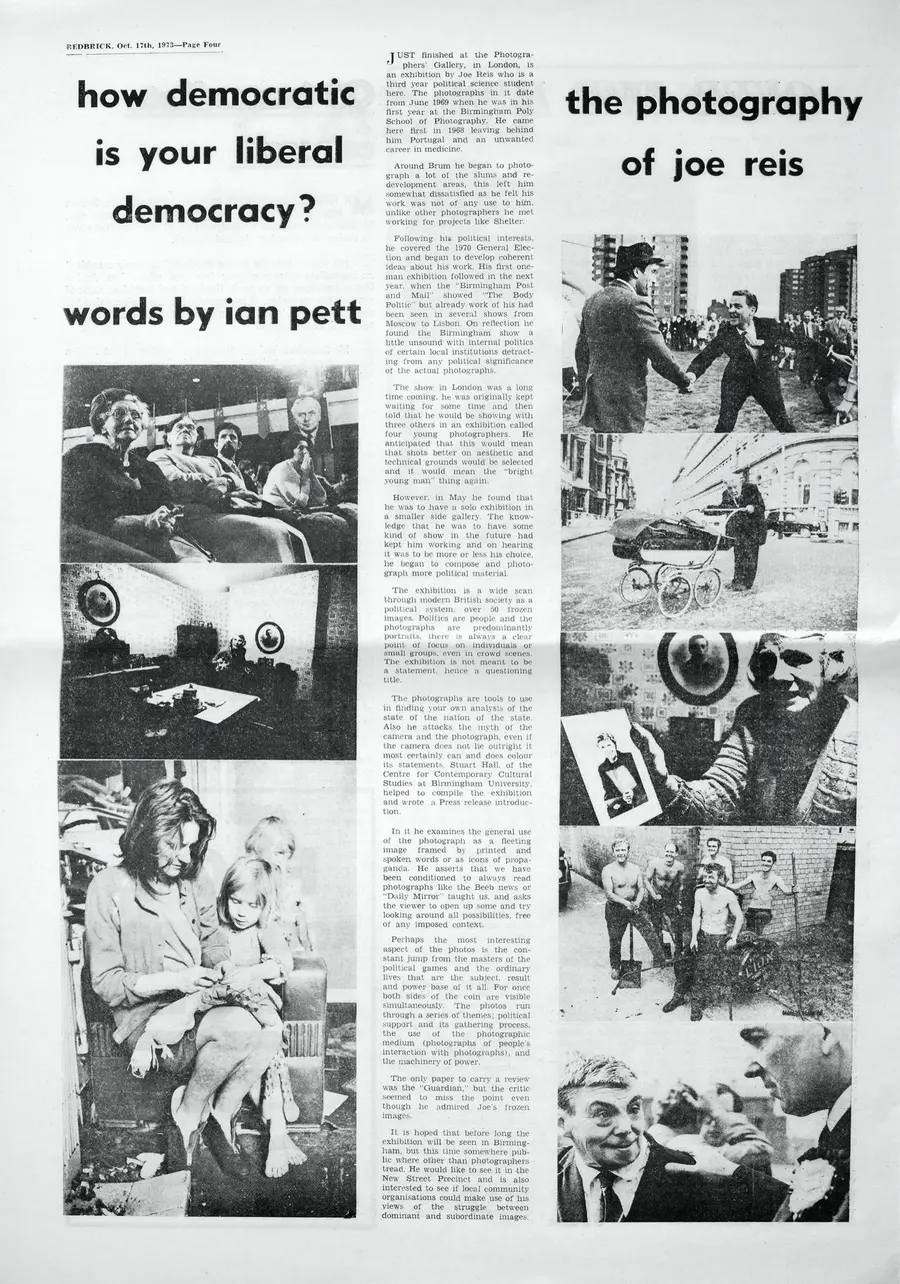

In the way we look, act, present ourselves to the world, we "say something" - deliberately or unconsciously - about who we are, what kinds of social individuals we are, what our positions are in society.

When persons become the "subjects" of a photograph, the photographer is, himself, offering a "reading", an interpretation, of his subjects and their social world. You can see this is the way the subjects appear, in how the photograph is taken, in the other images with which the subject is connected, even in what the photographer has "left out". When we look at photographs, we are ourselves making a "reading" of the readings which the photographer offers us. Something common, something dominant, is carried through from one of these presentations to the next. But there is always more there, more to be seen, more to be "read" - contradictory interpretations to be made of the subject matter of a photograph than we at first suppose. Photography seems to "capture reality" in an unproblematic way: it seems to "hold a mirror up to nature, to reflect actuality". This is an illusion: the illusion of naturalism. Photography is an interpretive art: it imposes one "reading" of reality over other "readings". We understand what the photograph "says" only because we possess a code which allows us to decipher its meanings. There are always more codes available. Dominant and subordinate "readings" struggle for pre-eminence in the images before us.

Photographs of public figures, or of politicians, or of the political process are among the most "natural" photos we possess. But that is because such images appear frequently, in the mass media, in a code with which we are familiar: that is the code of the news, of the news-photograph. There seems to be little more to find out about such photographs. The story is about the Prime Minister: and there he is, wearing a public face. The images of public men have already been pre-coded for us - as part of the "news". But the pictures themselves rarely become the subject of a political discourse: or rather, the political rhetoric, of which these pictures form a part, rarely itself becomes or is made visible. Public men are part of a public world and appear in public postures: that is one, self-contained world: is there anything more to be discovered there? On the other hand, ordinary men and women are outside the public world: we look on at the public world, and at the people who are part of its spectacle. When "we" are photographed, we are "ordinary people": the photographs of us are not "news", but "human interest". There we are, looking cheery, or stubborn, but confined within our own circle - the circle of the "human". What connection is there between the images of the "public" and the images of the "purely human"? Have ordinary people any right to "read" the images of public men in ways the subjects do not define for themselves? Do ordinary people have access to any code - any way of reading which would give them insight into how and why the public world looks like it does?

The temptation will be to bring to the viewing of this exhibition one of the already dominant codes of interpretation: to "read" the photos innocently. We will take the photographs at their "face value": we will "read" the photographs of public men like news photos, and the photographs of ordinary men and women like "human interest" photos. In this way we will miss the hidden connection. The public image of public men and the private image of ordinary men are the two sides of a single coin. The one is the condition of the other.

The intention of this exhibition is to bring these two sides of the political process into connection, and thus into visibility. To impose, if you like, on the viewer a "way of seeing", a "reading" of this hidden connection. The photographer himself takes the responsibility for making this connection visible, and thus for the question which arises from it, and which otherwise remains hidden. It is a question about politics. Your answer to this question depends, in turn, on how you read what has already been read.

Written by Stuart Hall,

Acting Director, Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, Birmingham University.

"HOW DEMOCRATIC IS YOUR LIBERAL DEMOCRACY?" Exhibition Text

By virtue of the way it has organised its technological base, contemporary industrial society tends to be totalitarian. For 'totalitarian' is not only a terroristic political coordination of society, but also a non-terroristic economic-technical coordination which operates through the manipulation of needs by vested interests. It thus precludes the emergence of an effective opposition against the whole. Not only a specific form of government or party rule makes for totalitarianism, but also a specific system of production and distribution which may well be compatible with a 'pluralism' of parties, newspapers, 'countervailing powers' etc.

Herbert Marcuse in "One Dimensional Man" (Abacus, p. 17).

I would like to invite you to use these photographs as tools to some thought on whether you agree with Professor Marcuse's words which raise some questions:

Are critics being effectively silenced by the channelling of their protests through harmless safety valves of institutionalised democracy?

Is society controlled through the manipulation of false needs created by vested interests?

Do bosses dominate? Is domination screened by a trans-figuration into bureaucrats and corporations?

Are "free institutions" and "democratic liberties" used to limit liberty, repress individuality, disguise exploitation or limit the scope of human experience?

These photographs do not intend to impose or provide you with an answer. They are just tools for you to use in correlating different aspects of life in the seventies in Britain, and elaborate your own answers to the questions raised.

Please remember that the activities of "reading" photographs, taking them or being photographed involve different roles and their actors may not necessarily share the same opinions or valuations.

Written by Joe Reis, 1973

For further information on this and past exhibitions, visit our Archive and Study Room.