21 January – 27 March 2005

To celebrate the Russian publication of David King’s book, The Commissar Vanishes, tracing the falsification of photographs and art in Stalin’s Russia, The Photographers’ Gallery is presenting an installation of haunting images drawn from a discovery made by the author in Moscow.

David King explains: “Like their counterparts in Hollywood, photographic retouchers in Soviet Russia spent long hours smoothing out the blemishes of imperfect complexions, helping the camera to falsify reality. Joseph Stalin’s pockmarked face, in particular, demanded exceptional skills with the airbrush. But it was during the Great Purges, which raged in the late 1930s, that a new form of falsification emerged. The physical eradication of Stalin’s political opponents at the hands of the secret police was swiftly followed by their obliteration from all forms of pictorial existence.

Photographs for publication were retouched and restructured with airbrush and scalpel to make once-famous personalities vanish. Paintings, too, were often withdrawn from museums so that compromising faces could be blocked out of group portraits. Entire editions of works by denounced politicians and writers were banished to the closed sections of the state libraries and archives or simply destroyed.

Soviet citizens, fearful of the consequences of being caught in possession of material considered “anti-Soviet” or “counterrevolutionary”, were forced to deface their own copies of books and photographs, often savagely attacking them with scissors or disfiguring them with ink. There is hardly a publication from the Stalinist period that does not bear the scars of this political vandalism. The subject matter of this exhibit focuses on one particularly evocative example: in 1934 the artist/designer/photographer Alexander Rodchenko was commissioned by the state publishing house OGIZ in Moscow to design the album, Ten Years of Uzbekistan, celebrating a decade of Soviet rule in that state. The Russian edition, full of Rodchenko’s skillful design techniques, appeared the same year and the Uzbek edition, with some politically induced changes, in 1935. But in 1937, at the height of the terror, Stalin ordered a major overhaul of the Uzbek leadership and heads began to roll. Many Party bosses photographed in Ten Years of Uzbekistan were liquidated. The album suddenly became illegal literature. Using thick black India ink, Rodchenko was compelled to deface his own book. The macabre results – ethereal, Rothko-like, sometimes brutal and terrifying – came close to creating a new art form; a graphic reflection of the real fate of the victims.

I first discovered and photographed the desecration of Rodchenko’s album 20 years ago in the winter of 1984, but it took me many years to find a completely undefaced copy. The concept of “personal responsibility” that had been forced on the whole country by the Stalinists, during a vast campaign of vigilance against the regime’s enemies, had seen to that."

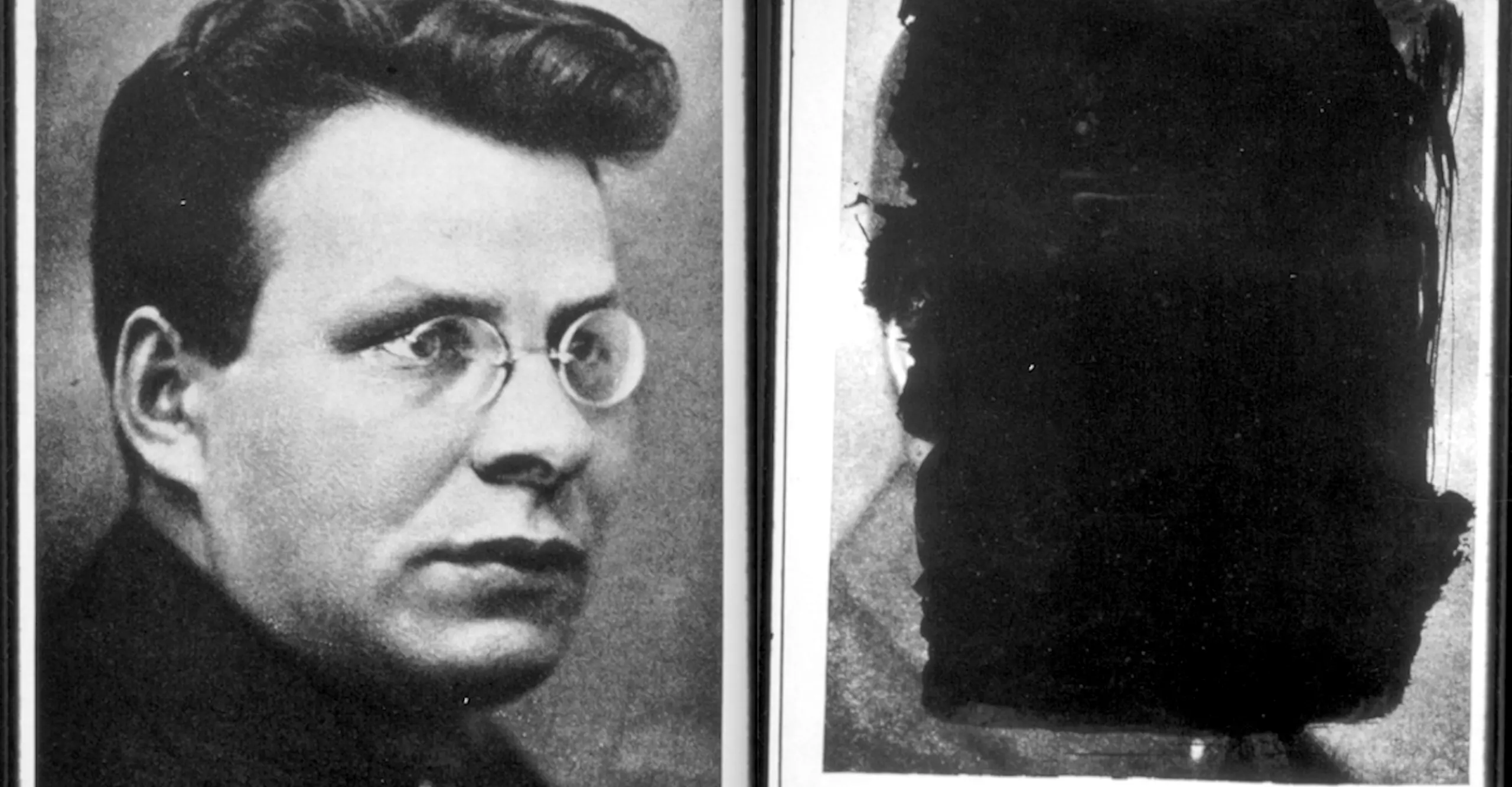

The Photographers’ Gallery installation now brings together, in the form of photographic enlargements, the published portraits of the high-ranking officials victimized in Stalin’s Uzbek purge, juxtaposed with their eradication by Rodchenko’s hand.

Digital photography has undermined our trust in photography as a factual recorder but the current exhibition serves as a dramatic reminder of the historical use and abuse of photography in the rewriting of history.

David King is a designer, photographer and Soviet historian. The David King Collection is one of the world’s leading photographic libraries, specializing in the history of Russia, the Soviet Union and communism globally. The archive, assembled over four decades, contains more than 250,000 original photographs, posters, graphics, journals, etc. New editions of The Commissar Vanishes are due to be published in Russia and France in 2005.

Yan Rudzutak, a Latvian from the prerevolutionary underground. Party member since 1905. Spent to power. Became candidate member of the Politburo in 1926. Opposed Stalin’s more grandiose proposals during the first Five-Year Plan, but his astute objections were swept aside. He was arrested at a party in May 1937. Among the guests also arrested were four women who were seen, three months later, in the Butyrka prison, still in their bedraggled evening dresses. One July 28, 1937, Yezhov sent Stalin a list of 138 names. Stalin scrawled “Shoot all 138.” Rudzutak’s name was on the list. The trumped-up charges included “spying for Germany.”

Yakov Peters, notoriously sadistic Latvian who was appointed deputy director of the Cheka soon after the Revolution. He worked in the East End of London from 1909 to 1917. Married an Englishwoman, May Freeman. Member of the British Labour Party. Chief of Internal Defense in Petrograd in 1919, where his work included the signing of innumerable death warrants. Key figure in the GPU, elected member of the Party Central Committee. Arrested and shot on Stalin's orders in 1938. His daughter, who was a famous ballet dancer, was also arrested.

Written by Charlotte Cotton, Head of Programming.

This exhibition relates to the book The Commissar Vanishes.

For further information on this and past exhibitions, visit our Archive and Study Room.