1 May – 21 June 1997

Photography, like museums, freezes things in time, stores them. Objects, like people, can reach eternity through it. Somehow, it reinforces, as it expands it, the idea of conservation, of museum. Little by little, photography has become the modern temple of memory.

José Ramón López - "Filing Procedures", Photo Vision 24, 1994

Many parallels can be drawn between the histories of photography and the public museum, but while museums have had considerable influence on public perceptions of photography, the reverse is not true. Camera Obscured proposes to begin to redress the balance in this dialogue.

In 1853, 14 years after the announcement of photography's invention, the first position of staff photo-grapher in a public museum was created. Roger Fenton (1819-69), soon to achieve celebrity status for his photographs of the Crimean Theatre of War, was hired by the Trustees of the British Museum to document its varied collections. Three years later the first in-house photographic studio was set up at the recently opened South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum). Significantly, the museum's staff photographers began to record not only the museum's collections but also the activities related to the enterprise of running such an institution, from the transport of artefacts to the construction and renovation of its buildings. Their photographs laid the basis for what has become an irreplaceable but curiously neglected visual component of the history of public museums. The idea that these photographs might constitute a collective body of work that allows us to see how museums have "seen" themselves has not been explored. Today, virtually all large public museums have in-house photographic facilities; some have had them for well over a century.

However, with the exception of Roger Fenton's work for the British Museum in the 1850's, much of the actual photographic output of those first photographers, and many of the others who have followed since, has remained little-known outside their respective institutions. While some important research has been done into the first years of photography at the British Museum and the Victoria & Albert Museum, much of the lengthy history of the use of photography by public museums to record their own activities has, ironically, gone undocumented.

The photographs in Camera Obscured represent only the tiniest tip of the massive iceberg of images that remain submerged in the archives of the world's public museums (the Metropolitan Museum of Art's institutional photo archive alone currently contains about 750,000 negatives). The photographs in this exhibition, drawn together from the archives of major public museums in North America and Europe, were produced between approximately 1856 and 1960. That 100 year period marks the time during which the large format camera was used by museums almost exclusively. This technological consistency, in combination with what can be described as the interpretive role of the museum photographer, has resulted in a legacy of finely detailed black and white images that enable us to carry out an "archaeology" of public museums. Literally they offer us the museum itself as artefact.

Vid Ingelevics

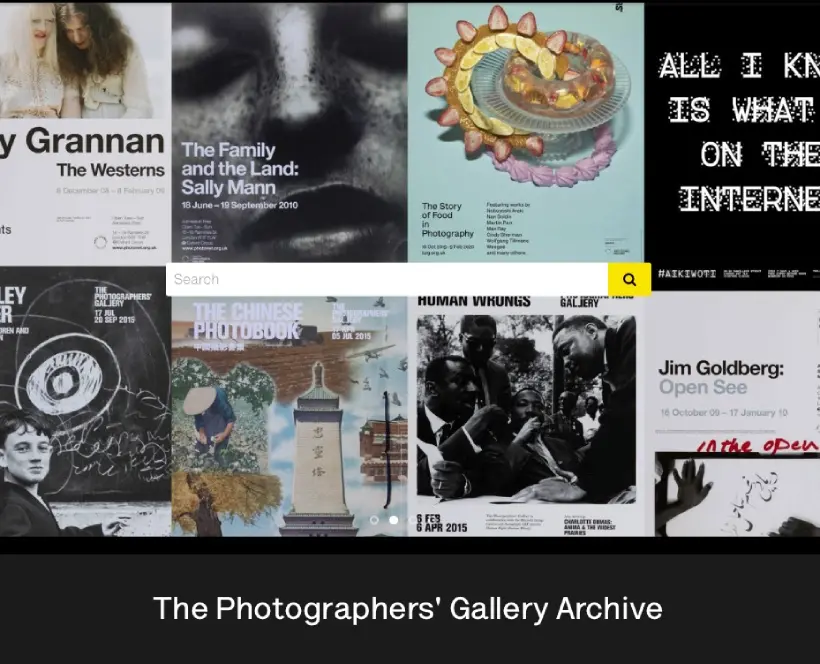

The exhibition was curated by Vid Ingelevics, originated by The Photographers’ Gallery and toured to North America by Toronto Photographers Workshop. For further information on this and past exhibitions, visit our Archive and Study Room.