This extended text forms part of the Light Years: The Photographers’ Gallery at 50 programme and accompanies the first in a series of four exhibitions focusing on 50 years of exhibition-making at The Photographers’ Gallery.

Curated by writer and researcher David Brittain, the first display entitled ‘Reportage: a worthy art for a new gallery’ examines the role photojournalism played in the first decade following the gallery’s inception in 1971.

The Programme of the 1970s

I started this diary while researching a quartet of themed exhibitions for the fiftieth anniversary of The Photographers’ Gallery. Each exhibition deploys archival material that relates to a dominant and enduring strand of programming (reportage, fashion and advertising photography, experimental approaches and archival research). The project is meant to be a celebration of the legacy of this remarkable organisation and an opportunity to ask a question that is related to that legacy, which is: what was the gallery's role in winning recognition for an art of photography? The question carries the presumption that The Photographers’ Gallery was not the sole agent of change. In fact, it was part of a system or network of individuals and organisations that included those, like the gallery itself, that belonged to photography, and those, like the Arts Council, that didn't. A version of this system was already in existence in 1971 when Sue Davies founded the gallery, and it has continued to evolve along with changes in image-making technology, methods of teaching photography, the politics of arts funding and the market - not to mention the shifting nature of photographic discourse. Any survey of The Photographers’ Gallery needs to acknowledge that its agency - indeed its existence - is dependent on collaboration and consent. I hope that these exhibitions will shed light on the work of the gallery and its identity as a node in a dynamic network. This text can be read as be supplement to the texts that surround those exhibitions.

My inspiration for this project was the gallery's exhibition history. Running to over 160 pages of A4, the document records the titles and the opening and closing dates of every exhibition since the start and who took part. It shows that the gallery organised around 300 exhibitions between 1971 and 1980 and it contains patterns that suggest the main trends in photography and the reach and limitations of Davies's ambition. Further research through archival documents reveals how the gallery has been shaped by its contact with different spheres of influence.

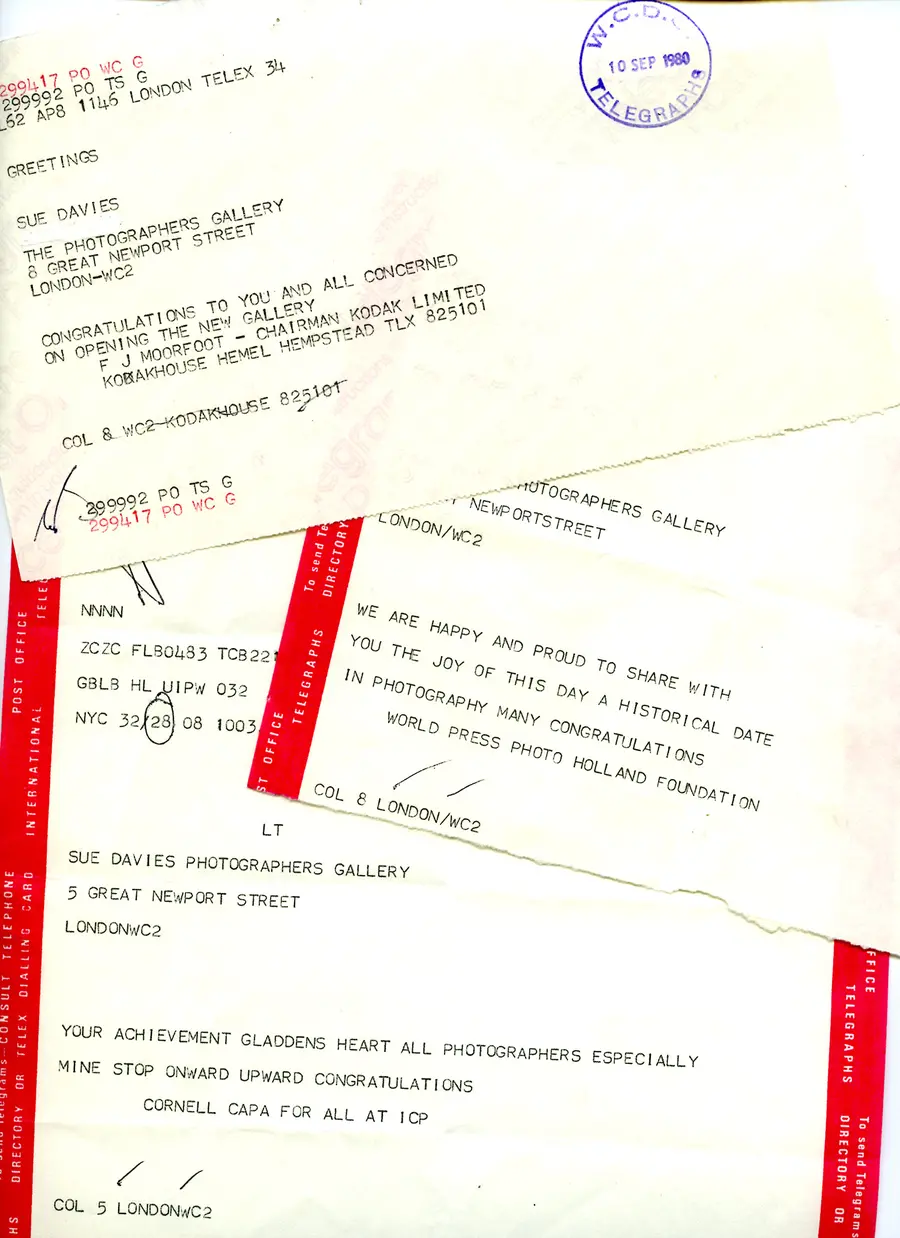

The Photographers’ Gallery officially opened on 14 January 1971 with 'The Concerned Photographer', a title from a time when photographs were still thought to be 'windows on the world.' Fragments of images from this exhibition can be glimpsed in the background of photographs that were taken at the launch party. One of those shows Davies, 37 at the time, beaming at an unidentified man. The old gent looking on approvingly is the photographer George Rodger, veteran of the Magnum picture agency. A rugged-looking Don McCullin appears in another picture, his back to a breeze block wall, and elsewhere the flash captures Dr. Roy Strong (as he then was) being stopped in his tracks by the journalist George Hughes. Dorothy Bohm, one of few established women photographers, is talking to Thurston Hopkins, and there's Bill Jay, the charismatic former editor of Creative Camera, holding court with someone who looks like a young Barry Lane. These people were the movers and shakers of the tiny black-and-white world of British photography. Some of them were invested in the idea of a gallery for photography (Jay ran his own short-lived commercial gallery and Lane wanted the Arts Council of Great Britain to support this one) and others lent Davies their support during the years and months leading up to this remarkable night. Davies, who once dreamed of becoming a journalist, had hoped to inaugurate her gallery with an exhibition of Magnum photography. When that wasn't possible, she embarked on her own exhibition about the 1968 cultural revolution which fell through despite the encouragement of Rodger. Then, by a stroke of luck, Cornell Capa's exhibition became available.

The exhibition programme that Davies initiated in 1971 then oversaw for ten years, owed much to precedent. Her debut in photography came in 1969 as co-organiser of a photography exhibition for the ICA called 'Spectrum'. The show of mainly editorial photographs represented a rare meeting between official culture and an emerging movement of artist-photographers. 'Spectrum' included the work of several of these photographers including Dorothy Bohm, Tony Ray-Jones and Don McCullin. When Davies was prevented from repeating the success of 'Spectrum', she resolved to open her own gallery for photographers like these. Previous efforts had failed because photography still lacked an audience and informed critics. Davies was advised to visit the US where institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York City and George Eastman House in Rochester successfully promoted photography as an artform. She made contact with both places on fact-finding trips that sometimes took her to Magnum's New York office or Light Gallery, the pioneering commercial space on Madison Avenue. The enormous influence of MoMA and GEH was felt in Britain through their scholarly, high-quality catalogues, and the opinions of their powerful curators which were published in elite photography magazines. It's no exaggeration to say that this kind of material prepared the buffs and enthusiasts of the 1960s to become the future supporters of The Photographers’ Gallery. Another influential source of knowledge was Beaumont Newhall's best-selling book, 'The History of Photography', which was expanded and republished in 1964. As is well known, Newhall was the first curator of photography at MoMA, which began collecting photographs as early as 1930. Nothing comparable had happened in Britain. To persuade the museum to accept photography as a modern art, Newhall devised a discursive mode of public presentation that he adapted from art history. Contentiously, this presupposed close and meaningful parallels between the realms of fine art and photography. Two parallels, specifically, became the foundations of an influential aesthetic discourse of photography: the photographer as autonomous artist and the original print as the manifestation of personal expression. Significantly, Newhall endorsed the 'straight' aesthetic of Stieglitz and his circle as the 'main tradition' of art photography. The critic Christopher Phillips describes how Newhall's aesthetic values translated into a viewer experience: 'Typically, the photographs were presented in precisely the same manner as other prints or drawings - carefully matted, framed behind glass, and hung at eye level; they were given precisely the same status: that of objects of authorised admiration and delectation.' Davies co-opted these presentation standards for her gallery along with the aesthetic discourse that underpinned them. Her programme combined solo and group exhibitions that were produced in-house or hired from better resourced organisations such as the Arts Council Collection or MoMA. On American lines, the exhibitions alternated between established or canonical photographers and emerging talent. The first survey of new British photographers was shown in April 1971, shortly after the grand opening. Davies also recognised the photographer's print as the expressive locus of their special genius. In the early days, visitors were ushered into a small sales area to be instructed in the appreciation of prints, then encouraged to make purchases. Some exhibitions, such as 'The Camera and the Craftsman' and 'Photograms and Further Experiments: Floris M. Neüsuss' (both 1975), were devoted to the craft aspects of photography - though matters of technique were of secondary interest to audiences, even then.

The first of my four exhibitions, Photojournalism: A Worthy Art for a New Gallery, features 'The Concerned Photographer' because it was such a prominent platform for the artist-photographer. In elite circles the recognition of photographers as 'artists in their own right' (as it was said) was thought to be a significant milestone on the road to full legitimation. 'The Concerned Photographer' comprised legendary press photographers including Robert Capa, 'Chim' Seymour and Werner Bischoff. In 1971 most informed photographers understood why these men, particularly, were classed as (borrowing Capa's term) 'witness artists'. Several belonged to the highly esteemed Magnum agency that was synonymous with its celebrated co-founder Henri Cartier-Bresson. A hefty exhibition catalogue contained the titles of the prestigious magazines they worked for (Robert Capa’s famous picture, Spain 1936, appeared in LIFE in 1937) and their books, exhibitions, and accolades (some had appeared in the fabled nineteen-fifties exhibition, 'The Family of Man'). To top it all, the version of 'The Concerned Photographer' that Capa sent to London included that giant of early twentieth century social reform, Lewis Hine, who brought the brand kudos and moral authority. 'The Concerned Photographer' looked to the past, yet it possessed contemporary relevance. It had opened in New York in 1967 as television began to eclipse the picture magazine as the predominant source of visual news. Young photographers who saw a future outside journalism struggled to finance their own projects and find an audience. 'The Concerned Photographer' was the public face of The Fund for Concerned Photography which Capa founded to inspire and motivate these artist-photographers. In addition to organising exhibitions (there was a 'Concerned Photographer 2' that came to London in 1974), the fund was an engine for monetising intellectual property (interestingly, The Photographers’ Gallery archive contains price lists for prints by Bischof and Leonard Freed from 'The Concerned Photographer'). Capa foresaw a range of potential sources of income in a manifesto that appeared in Infinity magazine in July 1970.

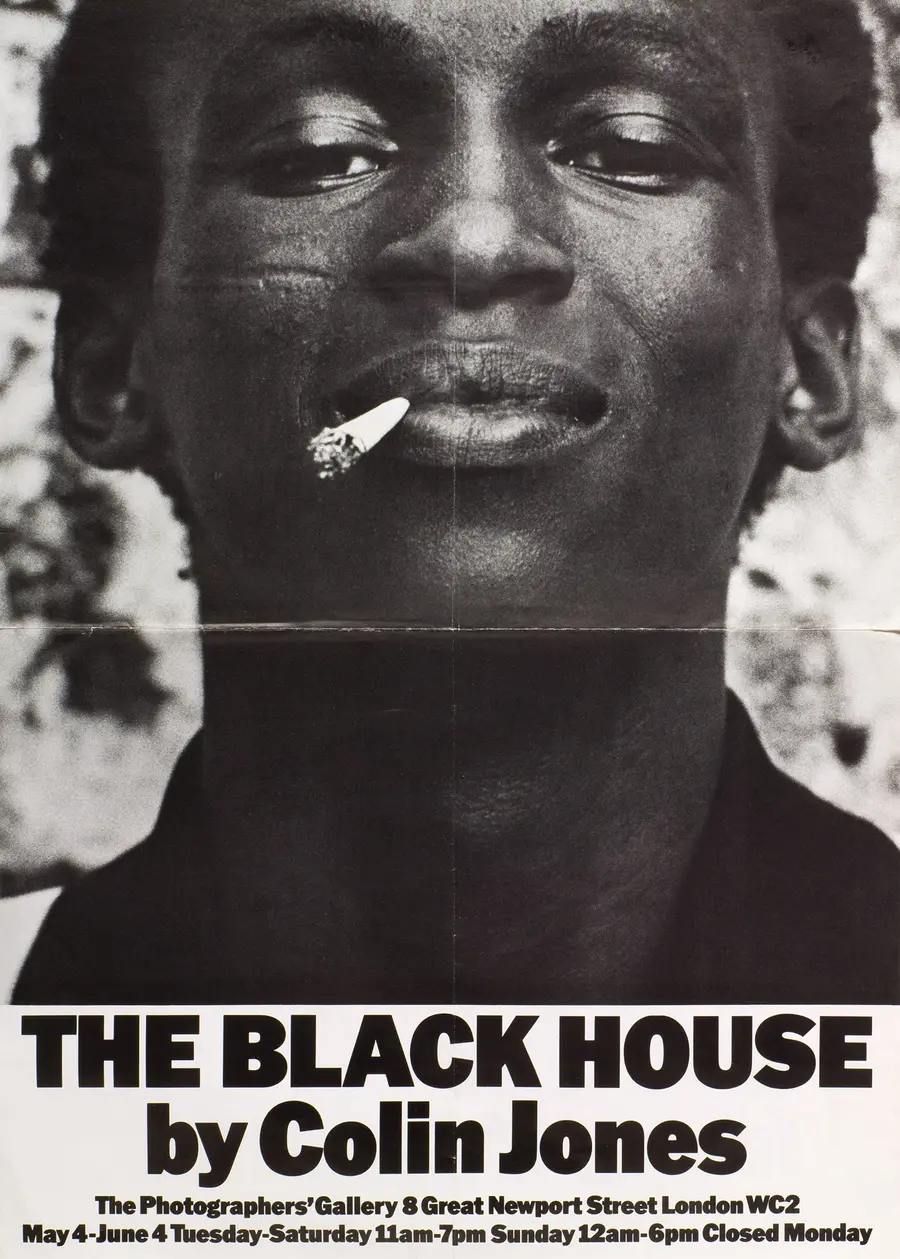

So, here was a pioneering photographer-centred organisation that married commerce with cultural aspirations. Parallels between Capa's model of advocacy and Davies's seem to be self-evident. Like Capa, Davies respected reportage photography as both an art form and a beacon of truth in a conflict-torn world. Eyewitness photography enjoyed the endorsement of elite magazines and museums, and featured prominently across the programme in its various forms. More importantly, it was appreciated by many people around the world who associated quality with the illustrated press. This helps to explain why reportage came to dominate The Photographers’ Gallery programme in the 1970s. This exhibition includes a range of original gallery posters that convey the prevalence of reportage within the programme and its diversity. Any exhibition with a title like, 'Current Canadian Photography' or 'Five Masters of European Photography' was likely to contain a significant proportion of reportage or documentary photographs. Davies's knowledge and appreciation of the subject benefited from many generous contacts in the press, including Magnum photographers like Capa, George Rodger and David Hurn, also Brian Duffy and Bryn Campbell from the Observer. Her circle included powerful journalists who were fellow travellers of photographers like Harold Evans, editor of the Sunday Times and the Observer's editor David Astor. They passed on the names of prospective exhibitors (including Colin Jones who exhibited in 1977) or volunteered to participate in the programme (some gave public talks and in 1978 the highly respected Evans arranged an exhibition of press photographs based on his book 'Pictures On A Page'). With their encouragement, Davies initiated a strand of exhibitions that was based on the journalistic assignment. Contributors to 'Two Views: Photographs of British Towns as Seen by Eight Photographers' from 1973, were commissioned by the Arts Council of Great Britain (as it then was) to observe and record events in society. Similarly, the work that comprised 'Families in France: A VIVA Photographic Essay' in 1973, had been specially produced for the gallery. Perhaps the picture magazine was the blueprint for the gallery programme. Davies's description of her role in the abortive exhibition about nineteen-sixty-eight sounds very like that of a newspaper picture editor: chasing agencies and photojournalists for images to illustrate different 'stories' (among her proposed sections were: 'Anti-Vietnam and Student Demonstrations', 'Black Power and Women's Liberation' and 'Communes, Eastern Cults and Religions'). Then there's Davies's practice of programming exhibitions in different spaces as if they were the contents of complementary editorial sections. Take for example, three historical shows that ran concurrently during May 1975: 'Frank Meadow Sutcliffe 1953-1941', 'The F64 Group: A Selection from the Henry Swift Collection' and 'Wish You Were Here: The History of the Picture Postcard'. I can imagine how this convergence of diverse perspectives and attitudes might have stimulated visitors to pay repeated visits.

Another of Davies's 'eyewitness' strands was press photography, which is acknowledged in the first of my exhibitions. In the early days at least, exhibitions of press photography were encouraged as a source of direct income for the gallery. A 1970 press release lists prominent media organisations including the Daily Telegraph, the Daily Express, the Observer and I.P.C. magazines (publisher of consumer titles like Women's Realm) as 'philanthropic' supporters. Once The Photographers’ Gallery got going, Davies urged these contacts to help by renting exhibition space. The gallery was still the only place in Britain where reportage photographs were given the respect of works of art. The Financial Times stepped up first in March 1971 with the 'Financial Times Industrial Photographic Awards', and sponsors were found for a run of annual exhibitions of press photography between 1972 and 1975. Minutes from a trustee's meeting in 1974 reveal that this arrangement yielded an 'estimated £2000' per year to put towards running costs.

When Capa included Lewis Hine in 'The Concerned Photographer' he knew the real beneficiaries would be the reportage photographers who were being inscribed into Hine's 'tradition'. The first chair of Davies's board was Sir Tom Hopkinson who makes an avuncular appearance in a couple of those launch party photographs. Hopkinson embodied a particular version of the history of photography that identified excellence in British photography with the illustrated press of the 1930s and '40s. Davies paid homage to this under-appreciated historical connection through a string of exhibitions featuring photographers who had worked with Hopkinson at Picture Post and Drum including Bill Brandt, Bert Hardy, Thurston Hopkins and Jurgen Schadeberg. One of the messages that was implicit was that meaningful continuities existed that connected photographers through the generations. This historical strand of programming may have helped to reinforce the contentious view of reportage as the dominant tradition in Britain.

The Photographers’ Gallery was well placed to nurture artist-photographers in the days when funding opportunities were limited. This is because the bookshop and the print sales department were organised as extensions of the exhibition programme. In the 1970s a book was a badge of artistic autonomy, and a fair proportion of exhibitions were based on publications. Between 1971 and 1979 The Photographers’ Gallery exhibited pictures from books by Gilles Caron ('Gilles Caron - Reporter'), Phillip Jones-Griffiths ('Vietnam Inc'), Jill Freedman ('Circus Days'), Elliot Erwitt ('Son of Bitch'), Patrick Ward ('Wish You Were Here: The English at Play'), the Exit group ('Down Wapping') and Janine Wiedel ('Vulcan’s Forge') to name a few. If a photographer was well established, the gallery might profit from selling their book (print buying didn't catch on until later). It seems that a greater proportion of pictures on display were works in progress towards a publication. Most of the nominally independent producers that were selected were relatively unknown. They came from all parts of the existing spectrum, including globe-trotting news photographers, 'freelancers' and even academics like Raymond Moore, and they were mostly male.

As we have seen, the gallery supported artist-photographers using commercial leverage within a mixed programme of exhibitions. Visitors in those days became accustomed to a rota of exhibitions that shuttled between advertising and fashion photography, 'erotic' photography, photojournalism, 'creative' photography, photographic postcards, scientific imagery and artists' Polaroids. Everything, in short, except pornography and sentimental 'camera club' photography. This wasn't quite the context that was preferred by an organisation like the Fund for Concerned Photography. The fund focused purely on reportage, giving prominence to the character and achievements of photographers over the industry that resourced them and brought their images to millions of readers. That idealised attitude contrasted with Davies's understanding of the relationship between photography and industry. When, in 1972 the gallery presented 'Cibachrome for Fashion and Advertising Photography', it was very clear that fashion and advertising photographers belonged to a large production system. The most vocal advocates of concerned photography accused magazine editors and designers of neutering the power of published images. The perspectives of 'Scoop, Scandal and Strife: A History of Newspaper Photography', where press images were viewed in their original contexts, and 'Pictures On A Page', told the opposite tale: of photographers and journalists co-operating to produce news. Davies's attitude probably reflected her vision of photography as a 'profession' and her respect for industry people including manufacturers such as Polaroid and Ilford, retailers like Pelling and Cross, Sotheby's salesroom, as well as newspaper picture desks. All this might suggest that the appropriate model for The Photographers’ Gallery was not the photographers' organisation but the art museum.

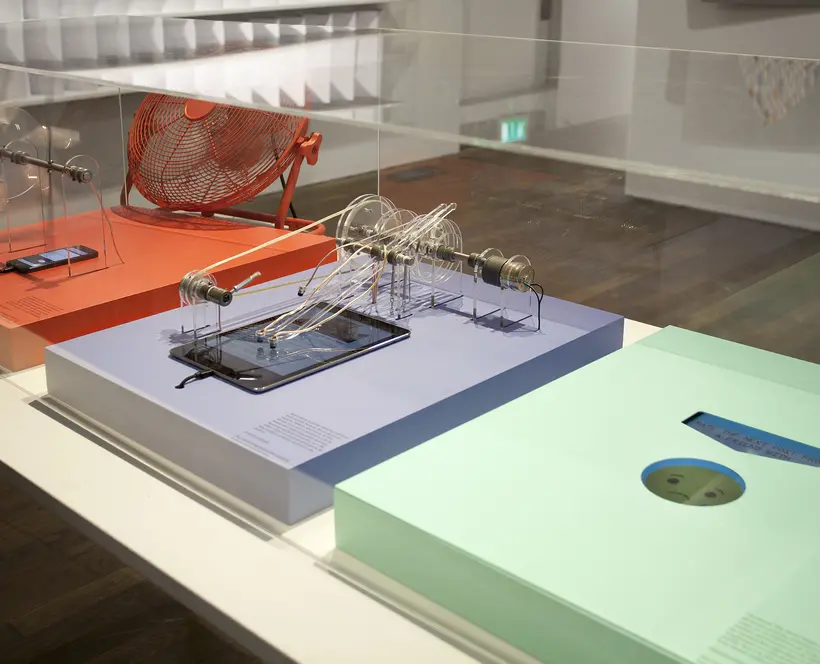

The gallery certainly aspired to the prestige of the museum. I have described how Davies adapted Newhall's presentation techniques so that photographs could be appreciated like works of art, and the way visitors were tutored in taste and encouraged to purchase photographers' prints. The cultural power of canon was enshrined in major exhibitions of 'straight' photography from Peter Henry Emerson, Weston and Brassaï to Cartier-Bresson, and the prevalence of reportage is one indication of its authority. I included gallery hand-outs and fliers in the exhibition that show how the language of connoisseurship was appropriated. Nevertheless, despite all of this, Davies demonstrated what might be called an 'anti-elitist' attitude towards all matters of high culture. For me, this is epitomised by her rollercoaster style of programming. The museum discourse insisted on a history in which a 'pure' art of photography developed independently, in isolation from the graphic arts and fine art. The Photographers’ Gallery programme, with its mixed cast of producers, attested to a history comprising intertwined histories and overlapping discourses. Some exhibitions, like 'Space, Focus Earth: European Satellites: The Men and the Techniques', of 1973, attested to a shared history between photography and applied science and technology. Another exhibition from that year, 'Joe Reis: How Democratic is Your Liberal Democracy?' pointed to the common roots of photography and agitprop. The social history of photography, meanwhile, was the subject of 'Wish You Were Here: The History of the Photographic Postcard' from 1975. Other social histories, such as that of the reproduction or the camera, are implicit particularly in exhibitions about techniques and processes. Some exhibitions, starting in 1971 with 'Andy Warhol: Polaroids', invoked the disruptive functions of photography within recent art history. A solo show called 'Cartes Postales' (shown in 1974) featured staged picture postcard views of cities taken by and featuring the conceptual artist, Nicole Gravier. While institutions like MoMA struggled to separate photography from its worldly functions, The Photographers’ Gallery seemed to revel in doing the opposite. Modernism located meaning in intention and form, but the collages in John Stezaker's eponymous 1978 exhibition pointed to a pre-existent world of images beyond the picture frame. There were 'troublesome' collaborations that frustrated claims, by experts like Newhall, that photographers unproblematically adopted the traditions and working methods of fine artists. One of the mainstays of the aesthetic discourse was authorship. In 1977 Chris Steele-Perkins and Mark Edwards put the question of authorship in doubt with an exhibition of accidental images of third parties called 'Film Ends'.

The Photographers’ Gallery was founded on precedent, yet it refused to conform to any model that was based on notions of 'purity'. Davies's programme represented a unique context for photography which succeeded in satisfying the conflicting demands of both the elite and the public. Where funding allowed, her exhibitions could be relatively spectacular. This exhibition includes little known pictures of Janine Wiedel's installation of 'Vulcan's Forge', in 1979. This shows how visitors were required to mount an elevated walkway of scaffolding to enter a maze of walls covered in floor-to-ceiling photographs. Six years earlier, for 'Five Masters of European Photography', Davies planned to liven things up with a back-projected film by Ed Van Der Elsken. Reviewers and visitors both seemed to appreciate Davies's bold curatorial style, but her critics identified some problems. In 1980 William Packer from the Financial Times questioned the status of the work on the walls. If photography was not yet legitimated, he wrote, had the gallery, 'blithely assumed the intrinsic worth of the material it showed ... and thus not so much won as brushed aside the argument of status.' What Packer alluded to, and no one ever explained (or dared to ask), was how the discursive function of the programme related to the gallery's core mission. There is no evidence of a manifesto, and the opinions expressed in exhibition catalogues of the 1970s belonged to gallery outsiders. If all photography was art, then why bother to promote an art of photography? The related issue of the integrity of the selection criteria bothered Euan Duff in his Guardian review of 'The Concerned Photographer 2'. Duff took exception to Cornell Capa's efforts to elevate the 'vitally concerned' photographer above his peers on grounds that: 'even the least perceptive or most commercial photographers can be “vitally concerned", and it is a conceit and presumption for anyone to try to justify their work on this basis alone…' There is evidence in minutes suggesting that Davies was aware of the need to find a voice for the gallery to clarify these questions. It's possible that she was under pressure to use the programme tactically, perhaps to define her ethos in relation to rival subsidised photography organisations. In the event, Davies determined to move ahead through deeds not words.

The Photographers’ Gallery exhibition programme of the 1970s was the public face of a complex and rapidly maturing organisation that sometimes struggled to define itself. I have identified key factors that shaped its programme, including the independent spirit of the director and her tastes and contacts, the low levels of appreciation for photography among press and public, and the emergence of artist-photographers with the decline of the picture essay. I speculated about the likely influence of journalistic formats like the magazine page and mentioned the significance of two dominant and contrasting American models of advocacy. We know from Davies's diaries that she was familiar with many influential people within the photography network: in picture agencies, commercial galleries, college courses and publishing houses as well as art museums. It would be hard to overlook the influence of Newhall's successor from the Department of Photography at MoMA, John Szarkowski. Davies knew and respected Szarkowski and left a touching sketch in one of her diaries. He did much to promote the ideal of an autonomous artist-photographer through exhibitions such as 'New Documents' with Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander. Controversially, Szarkowski characterised this kind of documentary photography as a quest for personal truths. It's possible that Davies's instinctive, magpie style of curating owes something to Szarkowski's exhibitions, 'The Photographer's Eye' (1964) and 'Mirrors and Windows' (1978). Like Szarkowski, Davies was less interested in elite or 'master' photographers than in photography itself. Her purview, like his, encompassed the canonical and the vernacular, though Szarkowski was not enthusiastic about reportage. In 1972 Davies hired 'New Photography USA' from MoMA and toured it around the UK. I'm sure that research into the partnership between these organisations could enhance what is known about the influence of American scholarship on British photography at this time. It would also be fascinating to know how dominant American publications were in the gallery bookshop.

What was the impact of the gallery's relationship with its core audience? When I began visiting in the late 1970s as a young journalist, the gallery was a Mecca for camera-carrying aficionados. Judging from the tone and content of the circulars of the 1970s, including a personalised member's newsletter, staff related to visitors as kindred spirits who shared their idealistic hopes for photography. In fact, relatively little is known about the constitution of that audience, including the proportion that were ‘professional’ photographers and how many came from abroad. Some were supporters who were closely engaged with the subject and could be relied upon to dip their hands in their pockets at fund-raising events, others went on the join the board or hold exhibitions. Davies valued photographers, and knew how to galvanise them, but we can only guess about the importance she attached to the collective spirit.

Around 1981 Davies stepped down from organising exhibitions to make way for a roster of talented young curators with their own agendas. Their contributions helped to change the programme in important ways, leaving it still wedded to Davies's idealistic personal vision: part advocacy, part education, part non-partisan support system. In her roles as director and chief exhibition selector, Davies exerted much control, but there were some things even she could not influence. Future research into the factors that shaped the early programme should consider the impact of financial constraints. Records show that money was tight. Davies's thrift was the stuff of legend (she didn't pay herself for the first two years) and she loved to tell journalists how she ploughed £3500 of her own money into the gallery (a significant sum at the time) and saved the day through some or other deal. But the financial situation for much of the early 1970s really was chronic, and it meant that opportunities were lost to exhibit interesting touring exhibitions that could establish the gallery as a serious player. Nevertheless, Davies was a skilful wheeler-dealer who knew how to make others feel invested in her personal crusade. Documents record the generosity of photographers including Cecil Beaton, Bill Brandt, and Terence Donovan who made unspecified donations. We know that other favours were offered, but not what they were or if anything was promised in return. Davies never concealed the fact that compromises were needed and were often made. Exhibition space was traded for financial donations in the early days. In her Director's Report of June 1976, she asked trustees for their opinions, 'regarding the amount of control over [sponsored] exhibitions we should insist on'. We don't know whether this practice raised any questions about the fairness of the selection process.

Any picture of the gallery would be incomplete without a better understanding of its relationship with the Arts Council of Great Britain. The ACGB's engagement with photography (and through its agency, the state's) began around the time The Photographers’ Gallery was founded and kept evolving with each new government. How much leverage did the ACGB and its photography officer, Barry Lane, expect in return for their support, and how much did they get? That is hard to gauge. Throughout the 1970s contributions from the ACGB helped to alleviate financial stress. During the first year of operation there was no Arts Council grant, but it subsidised the framing of a large exhibition of Lartigue's photographs. In 1972 The Photographers’ Gallery became a regularly funded client of the ACGB (£2000 a year, initially). Lane ensured compliance in areas that affected business and finance, including any income raised by the sale of books and photographers' prints, and from the rental of touring exhibitions. The most controversial source of revenue was the charge imposed by the gallery (25p or 10p for students or around £5.00 for an annual ticket ) for entry to major exhibitions. Records show that this was dropped in May 1974, but only after the ACGB agreed to increase its grant. This was no small thing, for as the critic Margery Mann noted in 1971, '[an admission fee] would be fatal to a photography gallery [in the US].' On the other hand, the ACGB clearly exerted influence on Davies's exhibition programme - something which tended to happen everywhere. Lane, advised by Peter Turner of Creative Camera, commented on the content of exhibitions and their presentation. Research into the area needs to acknowledge that photography suffered from chronic underfunding, compared with art galleries, because it was 'late to the funding table'. This explains Davies's mixed economy funding model, and why the gallery struggled to compete with better established venues.

Many doubtless well-intentioned commentators think The Photographers’ Gallery was solely responsible for changing attitudes towards photography in Britain. In my view it was part of something larger but hidden in plain sight. Resistance to an art of photography had been weakening throughout the 1970s - even while the Tate refused to show photographs - and the question: is photography art ceased to matter that much. As a journalist in the early 1980s, I became aware of the pattern and progress of change. I met planners at the Arts Council, and the curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum, whose Department of Prints and Drawings had been newly appointed the National Collection of the Art of Photography. I encountered publishers with plans for new monographs and noticed that shrewd minds at Sotheby's and Christie's were building client bases for photography. And I spoke to a few old hands from Cork Street who, in spite of themselves, were mounting and hanging photographs. They were not in this as altruists, of course, but because expensive postmodern artists like Cindy Sherman took snaps, and because it was good to have a toe in the water. The audience for photography grew more sophisticated because of such developments. Who knows what might have happened without The Photographers' Gallery, which was a trailblazer in so many ways. The organisation benefited from a popular and inspirational leader who enjoyed the ear of influential people around the world. I would say that its special contribution to that time of change was twofold: it helped to grow an audience for the art of photography and influence its tastes, and it established the principle of the photographer as an artist. Looking at it now, The Photographers’ Gallery of the 1970s seems to belong to another world.