This extended text forms part of the Light Years: The Photographers’ Gallery at 50 programme and accompanies the second in a series of four exhibitions focusing on 50 years of exhibition-making at The Photographers’ Gallery. Curated by writer and researcher David Brittain, the second display entitled ‘Fashion & Advertising: an anti-elitist art’ examines the opening up of the gallery’s exhibition programme through the 1980s and beyond. The previous Curator’s Diary 1 focused on the first decade at the gallery and can be found here.

The Programme of the 1980s

With the previous 'Curator's Diary' I provided some context for the first of four thematic exhibitions for the fiftieth anniversary of The Photographers' Gallery. These shows deploy archival material to explore the influence of the gallery and its identity within a dynamic network of organisations. This text considers developments during the decisive decade of the 1980s. As before, I am informed by documents in the gallery archive but this time I'm indebted to the former curator Martin Caiger-Smith who joined the gallery in 1985, for insights into the exhibition programme. The Photographers' Gallery was founded in 1971 by Sue Davies, whose 'eclectic' programme of exhibitions successfully ameliorated the contrasting tastes of the elite and the public. It was a grassroots operation, dedicated to educating and building an audience, and it spoke with Davies's voice. Things changed in 1980 when the gallery expanded and professionalised to take its place among major subsidised visual arts organisations. In 1988, three years before her retirement, Davies was awarded an OBE.

My primary research tool, the gallery's exhibition history, could be described as a map without a clear territory. In my version the first exhibition of 1980 (by John Blakemore) and the last one of 1989 (by Bruce Charlesworth) are separated by 48 printed pages. That's over 400 exhibitions, without accounting for print fairs, fund-raisers and other special events. As in the seventies, the programme consisted of solo shows, including retrospectives; surveys and group shows, including regular showcases of emerging talent from this country and abroad. A high proportion of these were generated by the gallery, including those from the print sales department. The frequency of exhibitions increased after 1980, following the gallery's £250,000 expansion into number 5 Great Newport Street. Davies named the main ground floor space the Tom Hopkinson Room, after her mentor - the former editor of Picture Post. Many visitors thought this was a popular cafe and meeting place with pictures on the walls. Caiger-Smith remembers its 'nineteen-sixties, seventies arts centre' feel, the smell of egg croissants and that it was difficult to see pictures. The Portfolio Room, which was reserved for untested work, wasn't a room but a ground-floor corridor that visitors used on their way in and out of the building. Ideally, this left the space in number 8 Great Newport Street for big shows that were 'research-based' or featured 'established figures' with the potential to attract sponsors. But even number eight was not safe from the encroachment of a busy bookshop. In practice, the scale of an exhibition, not the seniority of the exhibitor, determined its location (for instance, two major figures, Roy DeCarava and Helen Levitt, showed in number five in 1988, and very big shows would be divided across both locations).

In my memory at least, the programme was dominated by exhibitions that marked the big themes of the 1980s such as 'Mysterious Coincidences: New British Colour' (1987), 'Martin Parr: The Cost of Living' (1990) and 'Intimate Distance: Five Female Artists' (1989). There were those which introduced the latest styles and approaches from abroad (for instance, Grant Mudford's solo exhibition of 1977 brought with it the DNA of the New Topographics) which were hired from museums and came with their own catalogues. In fact, those ground-breaking shows didn't come around that often. Most of the exhibition programme consisted of the bread-and-butter of the photography circuit. Caiger-Smith remembers that a lot of content 'walked in from off the street' in the form of portfolio submissions. I vividly remember those piles of pictures in the curators' office that betokened the strong loyalties that bound the gallery to its constituency. We can't know how much the programme relied on such unsolicited material, let alone what much of it looked like. Part of the problem is that there were so many exhibitions and lots of them were undocumented. Other exhibitions were the result of collaborations. For example, 'Rubbish and Recollections: Keith Arnatt' from June 1989 was co-produced by Caiger-Smith and the Welsh curator Susan Beardmore. Meanwhile, book publishers and gallery managers had a mutual interest in exhibitions that promoted sales. 'Paul Reas: I Can Help' from 1988 and 'Martin Parr: The Cost of Living' from 1989, were Cornerhouse books. There was always a close synergy between the bookshop and the exhibition programme.

The Photographers' Gallery belonged to a competitive and still-expanding network of subsidised photography organisations of divergent identities and philosophies. This unique support structure for photography was also a dedicated market for The Photographers' Gallery's touring exhibitions (details were often included in gallery fliers). Along with sales and sponsorship, touring generated income (though it was more of a 'service') that was used to supplement the Arts Council grant. In turn, regional organisations were eager to tour shows to The Photographers' Gallery. During the 1980s it became a showcase for exhibitions from many of these organisations including Ten.8 magazine in Birmingham, The National Museum of Film and Photography in Bradford, Fotofeis in Edinburgh, the John Hansard Gallery, Southampton, the Brewery Arts Centre, Kendal, Side Gallery, Newcastle and the Cambridge Darkroom.[1]

In terms of content and variety, this programme resembles the one that Davies devised to help her grow an audience and establish the principle of the artist-photographer (Caiger-Smith describes it as 'a kind of melting pot' for all tastes). Yet there is evidence of a push and pull of tastes and attitudes that gives the programme of the eighties a vitality that it had lacked. To put a bit more flesh on my ideas, I plotted four paths across the sketchy terrain circumscribed by the exhibition history. Of course, I could have chosen other paths but some of those are already quite well trodden.

Path 1: Partnerships

The Arts Council and its regional partners had long been concerned about the diversity and inclusivity of the audiences and artistic programmes of their clients. In 1986 the issue came to the attention of The Photographers' Gallery board, probably not for the first time, when Barry Lane advised them to take the matter seriously. He is quoted as saying: 'do as much as possible through advertising, mailing or education to bring [yourself] to the attention of the Afro-Caribbean and Asian communities.'[2] This must have been an uncomfortable realisation to Davies who took pride in her organisation's liberalism and its relative accessibility to the public. In October 1983 Armet Francis had become the first black photographer to exhibit at the gallery. He was an editorial photographer and may have come to Davies's attention through her press contacts. The exhibition title, 'Black Triangle' referred to the slave trade route connecting Africa, the Americas and Europe. Then, a year later, the Bermudan photographer, Richard Saunders, exhibited 'The Lion Conquers'. This was a relatively small concession to ethnic diversity if you think that the gallery produced around 40 shows each year at this stage. But I have no idea how it compares to trends in other areas of the arts. Then there's the unfortunate coincidence that Francis's exhibition, which included Londoners of Afro-Caribbean descent, was preceded by Nancy Durrell McKenna's exotic pictures of African Bantustans.

Part of the gallery's response to the Arts Council was to strengthen ties with partner organisations such as the Birmingham-based collective Ten.8. This organisation identified itself with 'the politics of representation' and the exhibitions it toured included male and female producers from diasporic backgrounds such as Ingrid Pollard from 'Intimate Distance: Five Female Artists', from 1989, and Sunil Gupta, who featured in 'The Body Politic: Re-Presentations of Sexuality' in 1987. Ten.8 registers on The Photographers' Gallery's programme from 1984, through a series of innovative exhibitions, including 'Home Front' and 'Staying On: Immigrant Communities in London'. Many were produced in collaboration with the gallery curator Alex Noble who contributed text to issues of Ten.8 magazine that served as catalogues. The collaboration between Ten.8 and The Photographers' Gallery seems to have been mutually beneficial. The publication secured a better foothold in the capital through the gallery bookshop, while its exhibitions enabled the gallery to broaden its reach with both artists and audiences. The collaboration also helped to diversify the ecology of styles and practices (modes included installation, text and image and 'constructed' photography) within a programme that was still dominated by 'pure' photography. The partnership became the model for future collaborations between The Photographers' Gallery and other advocacy organisations, including Autograph (the Association of Black Photographers) which Armet Francis co-founded in 1988.

There were also partnerships with external curators who had their own areas of expertise. They included Val Williams whose 1987 exhibition 'Women Photographers in Great Britain: 1900-1950' (brought in from the National Museum of Photography in Bradford) agitated to admit women photographers into the canon. In 1988 one of the Ten.8 circle, David A. Bailey, approached the gallery with a proposal for an exhibition by the D-Max group of black photographers - Mark Boothe, Gilbert John, Dave Lewis, Zak Ové, Ingrid Pollard, and Bailey himself. D-Max (a technical term describing the deepest black which can be measured after printing) thought of exhibitions as a tool for countering the prevailing ethnic/ideological bias. The presence of shows concerned with representation and other 'critical' matters, gives the programme of the last half of the eighties a polemical/experimental feel that marks an irrevocable break with the past. This notion of rupture is a theme of my third exhibition, Beyond Documentary: from Photography to Photographies. I had hoped to attribute specific critical positions to individual curators, but Caiger-Smith cautioned against it because there was so much overlap and collaboration within curating (the person who did most of the organisation tended to write about the exhibition in the gallery publicity).

Path 2: Fashion and Postmodern Politics

If the 1960s was the heyday of fashion photography, then it took its place within the broader history of the art of photography during the 1980s. This was partly because of tenacious researchers like Martin Harrison who organised a run of popular exhibitions by Sarah Moon, Helmut Newton and Bruce Weber among others at the Olympus Gallery in London. Both the National Portrait Gallery and the Victoria and Albert Museum mounted exhibitions that helped to broaden the audience for fashion photographs; the latter with Harrison's 'Shots of Style' in 1986. There are many reasons for this resurgence of interest in fashion photography, and some are traceable in The Photographers' Gallery programme of the 1980s. The Print Room organised a string of shows by Cecil Beaton, Paul Tanquery, Angus McBean and George Hoyningen-Hueune, among others. This needs to be seen in the broader context of increasing market interest in early twentieth-century photography. Unlike commercial rivals such as Hamilton's gallery, the Print Room exhibited contemporary fashion photographers like David Hiscock and Koto Bolofo, following a trajectory begun in the 1970s when Davies exhibited Bailey, Donovan, Duffy and Helmut Newton, among others. Some of these contemporaries were connected to magazines such as The Face, i-D and Blitz that helped to feed an appetite for fashion images. These achieved far smaller circulations than better established rivals like Tatler and Vogue, but made up for it with innovative and irreverent design and exciting photography (think of the so-called 'stand-ups' in early copies of i-D that resemble police pictures).

In 1985 Alex Noble and Tony Arefin collaborated with The Face on an exhibition that examined aspects of the magazine's impact on the photography scene. This exhibition is the focus of my second exhibition in the Touchstone Gallery, Fashion and Advertising: Anti-elitist Art. 'Five Years With The Face' was designed by Neville Brody who would become the long-term resident designer at The Photographers' Gallery. The exhibition conformed to a familiar narrative in which The Face represented a return to a golden age of sixties fashion magazines (the magazines were the subject of Davies's exhibition 'British Photography 1955-65: The Master Craftsman in Print' in 1983). The difference was that a photographer who was attached to a small magazine like The Face enjoyed greater latitude for experimentation than someone who had worked for Town or Nova. This was amply demonstrated in a long-forgotten show at the National Portrait Gallery called 'Twenty For Today', a survey of editorial photography from the style press. In most shows of fashion photography - including those in The Photographers' Gallery Print Room - photographers were men and models were women. The Face, by contrast, catered for male and female readers and covered fashion, music, and cultural politics. The Face enlisted all styles of photography - even reportage - in its coverage, and significantly, editors gave photography exhibitions serious reviews. In a departure from convention, photographers' stylists were celebrated as co-producers. The magazine published many women photographers including Sheila Rock, Carol Starr and Jill Furmanovsky who featured in this show. Another regular, Cindy Palmano, appeared on the programme in 1989.

Davies was a great supporter of fashion and advertising photography and enjoyed connections to the 1960s through friendships with the former art editor of Queen, Mark Boxer, and with Terence Donovan and David Bailey. Her decision to support these practices displeased some people who thought that 'commercial photography' was less worthy than reportage. But her enthusiasm for the subject was shared with the young natives of the 'postmodern' media environment of The Face. In the opinion of the critic Dick Hebdige,[3] 'Five Years With The Face' brought the politics of that environment to the gallery. Normally, the gallery removed photographs from their contexts so that they could be endowed with the aura of works of art. These curators subverted the 'aura' by restoring the contextual elements of design and text and presenting photographers' prints as secondary to the 'original' reproductions. Four years later, in 'Out of Fashion: Photographs by Nick Knight and Cindy Palmano', other curators reintroduced context by using multiple wall panels and blow-ups to reproduce the effect of pages. It's interesting that fashion photography inspired relatively experimental curatorial methods, in relation to documentary photography for example. Is it a legacy from the days when applied photography was seen not to matter because it occupied a lowly position in the hierarchy of photographic art? Or is it simply that its themes of fantasy and escape lend themselves to this treatment?

Path 3: Theorists versus Romantics

The special relationship the gallery enjoyed with its audiences may have stemmed from the 1960s liberal roots of Davies and her circle. Unusually for a gallery, a proportion of exhibitors were also its core supporters, ensuring that the photographer's voice was heard in all areas of the organisation including its board of trustees. It is doubtful whether the gallery could have survived its first few years without the generosity and goodwill of photographers. With their backing, Davies commanded support from different sectors within photography, including manufacturers and retailers, and reassured public funders that the gallery was fulfilling its remit. It was in honour of this relationship that Davies christened the gallery and set aside the Portfolio Room in number 5 Great Newport Street for emerging photographers.

By the mid 1980s the gallery was enjoying the benefits of a climate in which photography enjoyed a certain legitimacy. The conditions that underpinned this - the photographer as artist, the print as the locus of his genius, and so on - were acceptable to loyal gallery supporters. They were, however, contested by younger visitors (pejoratively known to core supporters as 'theorists' because they were likely to be familiar with critical texts). Caiger-Smith and I remember how contestation and rivalry between theorists and core supporters (known to theorists as 'romantics' or 'modernists') formed a vexed yet exciting backdrop to the reception of many exhibitions of the eighties. This was particularly true for 'Constructed Narratives' (1986) that featured elaborately fabricated, colour pictures by Ron O'Donnell and Calum Colvin and a catalogue essay by me. I first met O'Donnell when he was looking for things to photograph in the junk shops of Edinburgh and East Lothian. His work was attracting interest as a break with the dominant black and white/documentary/master prints aesthetic, towards a 'postmodern' sensibility (loosely defined by practices such as image scavenging and 'constructing' pictures). I had been asked to write an article that could help to get him the attention of a gallery outside Scotland. So, I was pleased that Alex Noble wanted to put him together with Colvin in an exhibition for summer 1986. In our respective catalogue texts, Noble and I compared O'Donnell and Colvin with conceptual artists who conflated photography with sculpture or performance (I had John Hilliard in mind). Noble hoped her overtures might win over sceptics in contemporary art. I took the opposite view: that the people who needed to look at these pictures with an open mind were within photography. I knew that - even then - some viewers negatively associated the working methods and colour images of O'Donnell and Colvin with 'commercial' photography. I was aware that formalists might dislike their allusive imagery, while others would appreciate them. People who admired O'Donnell's work liked its anarchic but thoughtful humour. A popular picture featured three cardboard cut-out female film vendors and a kilted male mannequin. Surrounding them on an improvised stage was an array of signifiers of the photographic industry - cameras with huge lenses, busty salesgirls and oversized cartons of Kodak and Agfa film. O'Donnell titled this 'Doc Doc Document, 1986', which could have been interpreted as part of a sophisticated game of meaning, or a provocation aimed at a privileged style of photography. My text made a link between both these things. I seem to remember that 'Constructed Narratives' divided the audience along the usual lines. The first of my four exhibitions, Photojournalism: A Worthy Art for a New Gallery, contained one of the famous gallery comments books that provided a vivid snapshot of competing tribal attitudes. Visitors could also listen to extracts from archival recordings of gallery talks that capture the rapport between audiences and photographers. I think the most interesting thing about 'Constructed Narratives' was the symbolic space it occupied between photography and art, in which debate could take place. This portal remained open for the short time it took for this sort of photography to become acceptable, but it was long enough to introduce to a few new ideas.

Path 4: The Curator's Chorus

By the mid-1980s photographers were at last becoming recognised as artists - except within fine art which awaited the nod from the Tate Gallery. Some curators at The Photographers' Gallery thought it was possible to circumvent this obstacle through tactically re-branding photography as contemporary art. 'Constructed Narratives' demonstrated how this might be done by deploying colour materials and non-documentary methods to blur the boundaries between the formalist art of photography and postmodern photographic art. After 1986 the programme began to feature exhibitions that included contemporary artists. In 1988, for example, Caiger-Smith organised 'Plane Space: Sculptural Form and Photographic Dimensions'. This presented sculptural and photographic concerns on an equal basis and included two well established artists, Hannah Collins and James Casebere. At last, a Photographers' Gallery curator was overcoming long-standing internal resistance to exhibitions by artists (not from Davies, who was all for it). What seems to have changed? Through exhibitions such as 'Constructed Narratives' The Photographers' Gallery began to attract viewers from the contemporary art scene who lacked the cultural baggage of some supporters. Photography and contemporary art could seem almost indistinguishable through a common language of styles, forms and themes, and photographs featured prominently in the practice of more and more established artists. They included Collins and Casebere who were represented by Maureen Paley and Michael Klein, respectively. Art dealers such as these were normally reluctant to co-operate with a photography gallery unless they were persuaded that doing so was in the interests of their artists. Paley agreed to lend Collins then agreed to let Helen Chadwick exhibit in another Photographers' Gallery show, 'The Body Politic: Re-Presentations of Sexuality' (1987). She was also co-organiser of 'Photography as Performance: Message Through Object and Picture' (1986) that featured Joseph Beuys, Marina Abramović and Christian Boltanski among others. Another exhibition that combined artist photographers and photographic artists was 'Rapports: Contemporary Photography from France' (1987), an ambitious collaboration with the French curator Jean-François Chevrier.

These tentative interactions between contemporary artists and transgressive photographers helped to increase the prestige of The Photographers' Gallery and widen its appeal. Today we recognise them as a staging post to 2003 - the year of Tate Modern's first photography exhibition, that tipped photography belatedly into contemporary art[4]. As I have shown, The Photographers' Gallery made its own contribution to this change. The relative sophistication of the 'arty' people in the audience emboldened curators at The Photographers' Gallery to take risks.[5] Exhibitions such as 'Photography as Performance: Message Through Object and Picture', 'Plane Space: Sculptural Form and Photographic Dimensions', 'Bruce Charlesworth: Stranger’s Index' (1989) and 'Constructed Narratives' were important milestones, and more work needs to be done to reveal their significance in the broad context of photography in contemporary art in the 1980s. Some of these shows are a theme of my third exhibition Beyond Documentary: from Photography to Photographies. Even if they fell short in some areas, I am sure that they were successful in others. I wonder if photography galleries were in the vanguard of inter-disciplinary experimentation in those days. Curators like Caiger-Smith could afford to take risks because they enjoyed relatively more freedom than their counterparts in fine art, who had potentially more to lose.

Conclusion

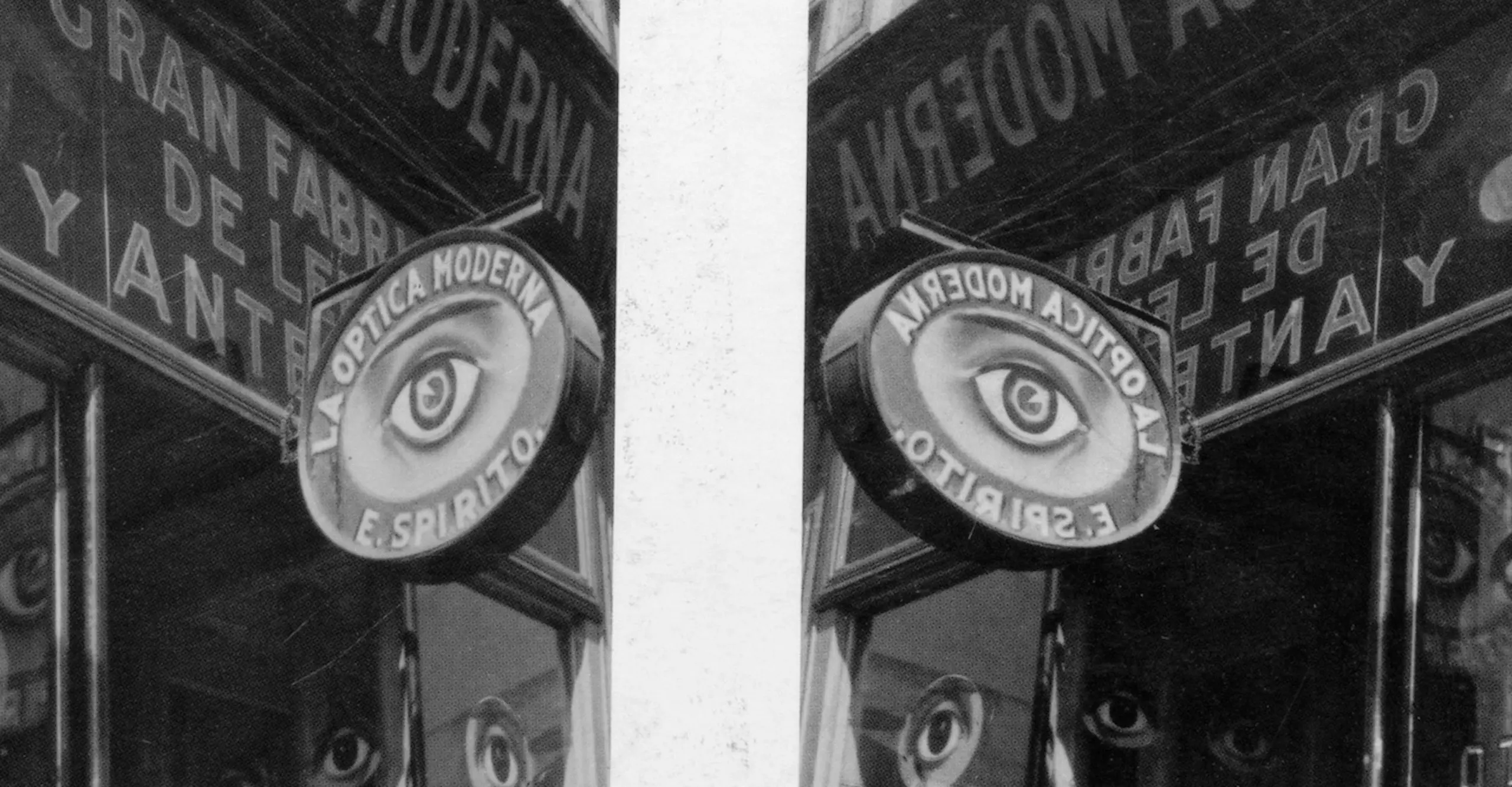

The expansion into number 5 Great Newport Street, coupled with a doubling of the gallery's annual Arts Council grant (to £90,000), offered an opportunity to address long-standing issues. After years of making do, Davies hired new admin staff and installed the print sales department in a dedicated gallery. Then in 1981 the founder announced that she was stepping down from organising exhibitions. This was effectively the end of the first phase of The Photographers' Gallery and there is some confusion about how it happened.[6] Did Davies stand down voluntarily or bow to pressure from the Arts Council? The archive contains a letter she wrote in December 1977 to John Szarkowski in New York. It refers half-jokingly to the Arts Council as 'always a slight problem' and ends with the comment: 'I will certainly take you up on your offer of help if things get very sticky.' After years of steering the gallery on a non-partisan course, Davies had attempted to embrace a well-established set of values with 'Concerning Photography: Some Thoughts About Reading Photographs' (1977). She contributed an upbeat introduction to a gallery-funded catalogue that was co-written by Jonathan Bayer, Ian Jeffrey and Peter Turner among others. We know from minutes that the Arts Council and its advisors didn't share Davies's enthusiasm for this show; and I can guess why. From the arcane title with its allusion to an autonomous art, to the male-dominated list of writers and exhibitors - including Bill Brandt, Walker Evans and Lewis Baltz - the exhibition identified the organisation with modernism. Davies was aware that a critique of modernism was underway[7], so did she not anticipate the likelihood of controversy? I think that it is more likely that she was made to feel that a critical perspective on the aesthetics of photography was in the remit of other funded organisations, not hers.[8] Whatever happened resulted in Davies handing the torch to younger curators. Rupert Martin was the first to arrive. He was followed by Alex Noble, Tony Arefin, Martin Caiger-Smith and David Chandler (though not necessarily in that order). They didn't know photography and photographers as Davies did, but along with external curators, they brought fresh attitudes and posed long-overdue questions. This initiated a new strand into the programme that I call 'experimental' photography - that cocktail of attitudes and styles that I referred to. Whether testing the boundaries of photographic practice, deconstructing photography through its social uses, or questioning who can enter the canon, the 'experimental' exhibitions of the 1980s opened an important new chapter for the gallery. One experimental avenue involved vernacular photography which is the subject of my final exhibition, The Archive: Collectors, Critics and Subversives.

It is Caiger-Smith's opinion that the programme of the eighties was not affected so much by competing curatorial agendas as by 'the generational divide' between director and curators. He remembers Davies arguing to keep 'professional photography' in the programme. She lobbied hard for reportage because it was popular and plentiful, and was, in her personal opinion, the authentic expression of the art of photography[9]. The eyewitness strand continued to encompass vintage material, as seen in 'Festival of India: Photography in India 1858-1980' in 1982, contemporary documentary projects like 'Paul Graham: A1: The Great North Road' from 1983 and high-profile commissions such as 'Britain in 1984' (featuring Don McCullin and Raghubhir Singh).

Another important trend was the growing acceptance of photography as 'an art in its own right' (as it is worded in Photographers' Gallery documents). By the mid 1980s the gallery began to enjoy the advantages of the provisional form of legitimation it had helped to create. The Print Room, which shared Davies's passion for editorial and advertising photography, watched sales increasing on the back of a maturing market for photographers' prints. There was, arguably, greater choice in the bookshop and more demand as the audience for photography became educated and grew more discriminating. More importantly, a legitimated photography benefited established producers who identified with traditional values and methods. They included Martin Parr, Peter Fraser, Anna Fox, Chris Killip, John Davies, Jem Southam and Fay Godwin. The status quo brought them respectability, opportunities, and market interest. That decade the Print Room staged solo exhibitions by Parr, Killip, Godwin, Olivia Parker, Graham Smith and other contemporaries. Artist-photographers were easily identified with any one of the newly-legitimated 'traditions' of the art of photography - from social documentary (known as 'soc doc') to New Documents to New Topographics. As I have shown, a sense of legitimation inspired a run of exhibitions that pushed for photography to be recognised as a contemporary - not an autonomous - art. The strand featured artists who exploited photography but also formerly proscribed producers such as Jo Spence or Graham Budgett who were at the interface of photography, politics and art. Would these exhibitions have been possible without the singular context of The Photographers' Gallery? As we know, full legitimation didn't happen until 2003. For this reason, Martin Caiger-Smith describes the 1980s as a 'transitional period'.

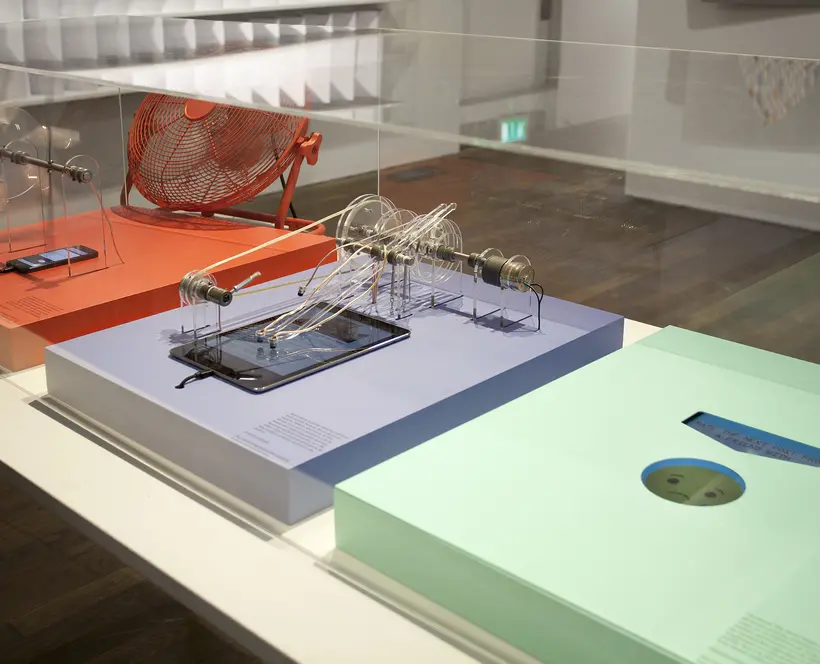

Another trend which becomes evident with the benefit of hindsight is that many things appear to have been in transition. I have mentioned the shift from art photography to photography as contemporary art, and the way fashion photography, once the Cinderella of the art, became accepted by young viewers who lacked the prejudices of their forebears. Significantly, the period also witnessed the transfer of power from the idealistic, DIY generation of Sue Davies (who retired in 1991) and her circle to younger, more managerial actors. Again, hindsight shows that the gallery of the 1980s was in a transition from the era of analogue to the threshold of the digital age (I remember handling an early digital camera in 1986 or 87). It's interesting that one of the last shows of 1989 was 'Machine Dreams: A New Technology' that included digital work from the likes of Calum Colvin. Curated by David Chandler, it looked forward to the gallery's fruitful engagement with new media (and media politics) during the 1990s and into the present day. Finally, I would say that the 1980s marked a gradual shift in the way The Photographers' Gallery was perceived (including how it perceived itself). Feted during the 1970s as the independent champion of the underdog, it came to represent the establishment after 1980 (for better or for worse). Inevitably, this consolidation prompted some people to ask whether photography still needed a champion.

I realise that this diary contains traces of many paths across the territory that weren't travelled because of constraints on space and time. But I very much hope that future researchers might consider it as a start. My thanks again to Martin Caiger-Smith for his time and insights, and to The Photographers' Gallery staff for providing me with remote access to material.

Footnotes

[1] The gallery also toured exhibitions to colleges and other non-specific organisations.

[2] The minutes of February 1986 it is recorded that the photography officer, Barry Lane, addressed the board on this topic.

[3] Hebdige D., 'Hiding in The Light', Routledge, London 1988

[4] Photography had been for some time constituted within the visual arts department of the Arts Council of England

[5] Minutes from November 1988 record that Martin Caiger-Smith reassured concerned trustees that: 'the programme was maintaining a balance between difficult and easy work [because] audiences were becoming increasingly sophisticated ...'

[6] Davies told the British Library Oral History of British Photography (tape 6) that she organised exhibitions for 12 years, but the 'British Journal of Photography', 14.2.1991, records that, 'after 10 years .... Davies took on a greater administrative workload and sacrificed the exhibition commissioning and organising' to other staff.

[7] Walter Benjamin's perspective on the politics of reproduction, and the 'male gaze' of second-wave feminism helped to inform the TV series 'Ways of Seeing' in 1972. Other examples include Victor Burgin's seminal essay about photography and theory that was published in 1975 in Studio International, and 'On Photography' by Susan Sontag that appeared in 1978. Among the 'Statement of Aims' printed in 1976 in issue number 1 of 'Camerawork' is: 'By exploring the application, scope and content of photography, we intend to demystify the process.'

[8] There is evidence that Davies was concerned that the gallery was out of step with the times. In her Directors' report of 10.6.1976 she writes: '... we must make more meaningful and even didactic exhibitions and that to continue simply hanging up the work of individuals month after month in a rather similar format is not in fact accomplishing very much... I feel we should stick our necks out a little further without harm. Certainly, if we do not begin to make some statements about the meaning and uses of photography other people will do so.'

[9] Possibly in response to questions, Davies justified the prevalence of reportage in a communique of 1973: '... I realise that we have probably included rather more reportage than anything else, partly because it is very varied in itself and partly because it causes less problems on the whole and more photo journalists than advertising photographers have brought us work and shown an interest in having exhibitions.'

David Brittain’s Curator’s Diary pt2 can be found here